In September 1940 the Dutch abstract artist Piet Mondrian arrived in New York, a refugee from war and the London Blitz. He was sixty-eight, a well known figure in modern art circles in Europe but as yet little appreciated on the other side of the Atlantic. His visas, his travel and his accommodation had been sorted out for him by well-wishers in Britain and he was welcomed in America by Harry Holtzman, an artist some forty years his junior. On the evening of his arrival, Holtzman entertained the stiff, fastidious, well-dressed Mondrian to dinner in his apartment and introduced him, via the phonograph, to boogie-woogie. He recalled:

Mondrian’s response was immediate, he clapped his hands together with obvious pleasure. He sat in complete absorption to the music, saying, ‘Enormous! Enormous!’

In Mondrian: His Life, His Art, His Quest for the Absolute, Nicholas Fox Weber’s description of the evening and of the days that followed gives us, as does his entire biography, as intimate and exhaustively detailed a portrait of this elusive and contradictory genius as we are ever likely to get or want. He looked, Weber tells us, like a Dutch businessman but was often dependent financially on his friends. He was awkward in company, at times taciturn and rude, but inspired affection and loyalty in a succession of friends. He advocated — and lived — an ascetic and simple existence, but relished dancing to the latest jazz. He adored and was inspired by nature, but came to find the outward expression of his love in the pure abstraction of his art.

Born in 1872, Mondrian was the eldest child of an orthodox Protestant headmaster and was brought up in rural Holland in a rigorously devout household. His father was an amateur artist of some merit, and his uncle, Frits Mondriaan, an established painter in a traditional style whose work was well known in Dutch art circles. Both men fostered the young Piet’s early talent and encouraged him towards a career as an art teacher. Dutifully, he passed the necessary exams; but teaching was never going to be his metier and after a brief stint at the Rijksakademie he launched into the wider world of Amsterdam to make his living as a professional artist. He illustrated religious books, painted tiles, made portraits and landscapes and paintings of buildings and flowers, designed panels for a pulpit, made technical drawings of bacteria, taught drawing privately, copied old masters in the Rijksmuseum and twice failed to win the Prix de Rome.

At the same time, however, he was slipping the religious and artistic straitjacket of his upbringing to become a theosophist and anarchist and produce landscapes of an increasingly abstract nature. Intense in their color and bursting with light, they found favor with the avant-garde, appalled most critics and horrified Uncle Frits to such an extent that he demanded Piet drop the second “a” in his surname so the two would not be associated.

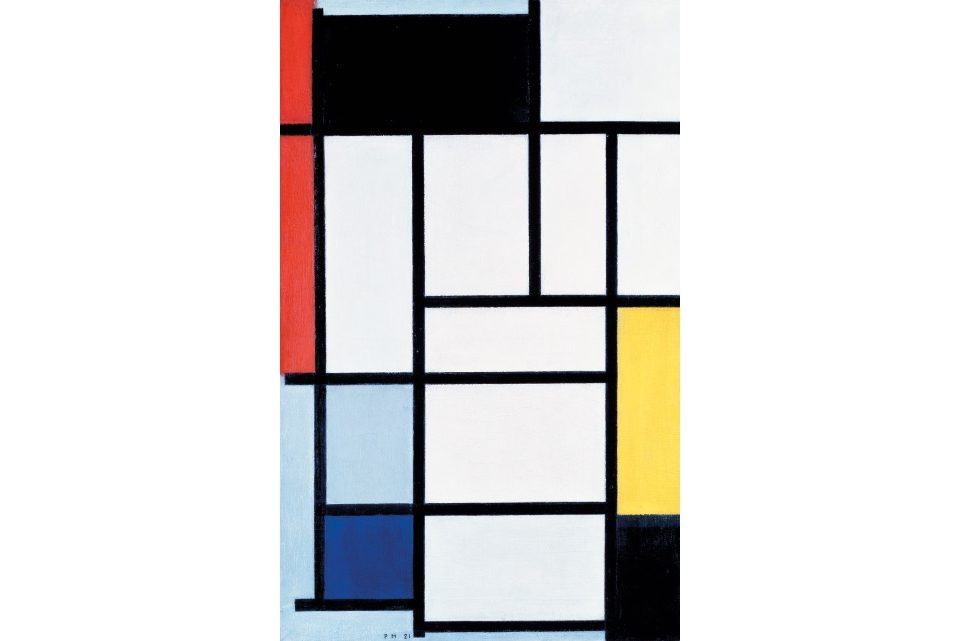

Mondrian’s mature work — the white, red, blue and yellow blocks criss-crossed with black gridlines — is such a cornerstone and seemingly inevitable “fact” of modern art that it’s important to be reminded that it did not spring fully formed to its creator’s hand. He later wrote:

The first thing to change in my painting was the color. I forsook natural color for pure color. I had come to feel that the colors of nature cannot be reproduced on canvas. Instinctively, I felt that painting had to find a new way to express the beauty of nature.

Weber notes various factors that may have influenced Mondrian’s mature style — such as the symmetrical arrangement of the window bars in his childhood home; but it was sketches he made of buildings being demolished that led ultimately to the grid paintings with which he is most readily associated. From the start of his experiments in pure abstraction he had his admirers, few in number perhaps but helpful both practically and financially; his paintings began to be seen in exhibitions in the Netherlands and Germany and acquired by such influential collectors as Helene Kröller-Müller and Peggy Guggenheim.

As he perfected his elegant, sophisticated paintings and pared down his colors and forms, he began to express in writing a personal philosophy which would emerge as Neo-Plasticism, the principal tenet of the De Stijl group. In letters and essays, Mondrian endlessly repeated his belief in the “transitional” power of what he was doing, of an art that, refined and painstakingly reworked, took artist and viewer to a “spiritual realm” where perfect equilibrium was to be found. “They take action; they move,” writes Weber of the gridlines, “they jump, or glide, and then they hold themselves. They have authority and power and clarity, yet they are without a hint of arrogance.”

While a reader would be in a far better place to judge the validity of Weber’s interpretations of the paintings if there were more illustrations, his portrait of the artist is unlikely to be challenged. His Mondrian is a man driven by his vocation. Not particularly likable — an antisemite who was helped throughout his life by Jewish friends; a misogynist in spite of his many women friends; a companion who could drop a long-standing relationship in a heartbeat — he lived for and in his art. Whether in New York, Paris or London apartments, his frugal, almost monastic, world was a Mondrian world: whitewashed walls punctuated with cardboard rectangles painted in primary colors; white furniture made from fruit boxes. The atmosphere in his studio, as Ben Nicholson so nicely put it, “must have been very like the feeling in one of those hermits’ caves where lions used to go to have thorns taken out of their paws.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.