At a miserable-looking rally for France’s center-left Place Publique party in March, its co-president, Raphaël Glucksmann, made international headlines calling for the Trump administration to return the Statue of Liberty, presented by the French in 1886 to commemorate the Declaration of Independence: “It was our gift to you. But apparently you despise her. So she will be happy here with us.” The predictably sensationalist headlines dissipated in a flurry of Republican outrage against “the low-level French politician” as quickly as they arrived. But Glucksmann’s demand – sincere or not – caught the attention of a group of sculptors who, in their words, have “taken up the dream of civilization” to produce monumental civic sculpture.

Two days after Glucksmann’s proclamation, Atelier Missor posted on X: “Keep the Statue of Liberty; it’s rightfully yours. But get ready for another one. A new Statue of Liberty, much bigger, made from titanium to withstand millions of years. We, the French people, are going to make it again!” It was accompanied by an AI-generated image of Liberty’s future titanium partner, Prometheus. So far, so American Golden Age, validated by a typically laconic reply from Elon Musk: “Looks cool.” The exchange was a public-relations coup for Missor – and decried as such by cynics. Surely no one believed that this hare-brained scheme could be feasibly implemented? Think again.

‘The Statue of Liberty represented the most beautiful thing a country can do: it was by the people, for the people’

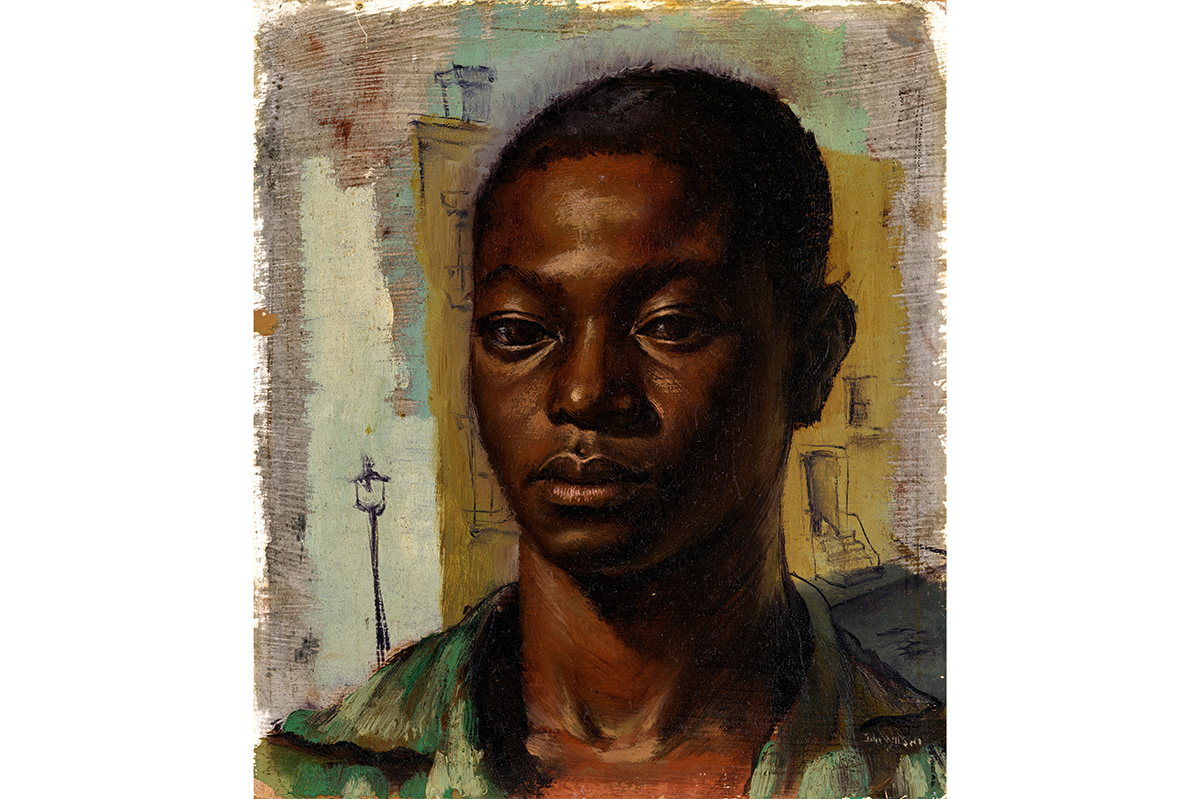

To understand the sincerity of Missor, one must return to where its ambitions started. “I found the toppling of public statues intolerable,” the atelier’s founder Missor Movahed tells me at its studio on the outskirts of Meaux, 40 miles northeast of Paris. “I did not understand what these people were doing or what they were saying. Would they rather these great men had never existed?” he says, referring to the convulsive, iconoclastic riots of 2020 – the respective beheadings and defacements of Columbus and Churchill. Movahed was 30 years old and had no prior sculptural training. He and his friends began discussing the postmodern cultural malaise on a YouTube channel from a disused garage in Nice, with the ambition of producing small figurative busts, at scale, of the luminaries to whose lives and writings they were turning: Nietzsche, Napoleon, Joan of Arc, Dostoevsky.

The son of a successful painter, Movahed grew up in Paris with neither plans nor qualifications: “For 12 years, I did nothing with my life: I led a life of a wastrel bohème. But being in Paris – the greatest work of art in the world – I felt a growing weight to produce something monumental… to create monuments that will stand on the landscape of humanity.” All simultaneously informed by and documented on YouTube – a kind of modern cahier – the group constructed rubber molds and later a working smelter for limited-edition bronzes, fashioned by hand. “There is no sculptor or foundry that produces classical civic sculpture in France to whom we could apprentice ourselves: all of them have closed, other than those we have on the internet.”

Don’t mistake the lack of formal training, however, for a lack of rigor or thought: “We sculpt the statues out of clay, always questioning what one of the Greek philosophers would say if he were watching… [Only a few other] highly specialist sculptors are using the 1,000-year-old ‘lost wax method.’” This process involves 1,600°F molten bronze being poured into plaster casts of wax models. Within six months, orders were in the hundreds; by their third year, they numbered more than 5,000. Online, Missor had captivated a receptive audience, one that was seeking a resurrection of its European cultural inheritance.

In August 2023, Missor received its first public commission: a €170,000 gilded bronze of Joan of Arc from the center-right mayor of Nice, Christian Estrosi. The 15th-century soldier-saint is a figure fiercely contested in France: à gauche, a martyred, cross-dressing teenage farmer; to the right, a devout Catholic rebel who lifted the siege of Orléans. Delivered a year later, the nine-ton, 15-foot high statue was unveiled in December at the inauguration of a new car park next to the Église Sainte-Jeanne d’Arc.

But there was a problem: the commission was found to have broken public procurement obligations and in January this year it was ordered that Joan should be removed. It sparked a huge backlash and in March, protesters arrived by dawn to pour a layer of asphalt around the base. They made it clear: Joan was going nowhere.

There is no sign of the impending threat of prosecution when I arrive at the atelier, a corrugated shed off the Parisian suburban line: a dozen workers in dungarees – a uniform they trace to the compagnons du devoir who built the French cathedrals – are methodically plastering a monumental classical face surrounded by scaffolding. For nearly three hours we speak, standing between remnant prototypes and plaster models now the subject of public – and legal – controversy. “All sculptures are public memories that last, until we topple them, and by not making them we are losing our memories,” Movahed says. “There are many who are artistically revolted by what we do as a momentary reaction to contemporary art. But there is a morbidity to civic ‘fine art’ today because of the way it depresses those who have funded it – us, the people.”

He explains that titanium has never been used before for figurative sculpture. He views it as “the frontier of both engineering and art – two things that must work together.” And for him, the Franco-American alliance that spawned the Statue of Liberty was more than simply a historical fact: “The founding myths of revolution that underpin the French and American republics represent an emancipation of the individual will and an unleashing of potential.”

He adds: “The Statue of Liberty represented the most beautiful thing a country can do. It was by the people, for the people. Prometheus will represent the possibilities of modern patronage: we have received hundreds of messages asking us to open crowdfunding.” Indeed, Movahed does not name the “significant American backers” that have pledged support, but cites Musk’s Starbase as the intended location. A tiny bronze maquette of the rebel Titan – credited with shaping humans from clay – sits on a pyramidal pedestal no taller than a hand that will “chart the history of civilization.”

It is a world away from Boca Chica, Texas, and the task Movahed illustrates with maddening conviction under a looming court order is beyond reason. “We are called crazy, but our aim is simple: to let people dream as we have chosen to dream.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply