Noel Parmentel’s quote, “The right wing was fun back then,” is one of the takeaways from Daniel J. Flynn’s new book The Man Who Invented Conservatism: The Unlikely Life of Frank S. Meyer. Fun? The progenitors of post-World War Two American conservatism were, as portrayed here, a high-spirited lot. They were also intemperate, combative, self-destructive, often brilliant, not infrequently loony – and always deeply interesting.

One could apply those qualities to the subject of the book, a character who looms large in the minds of intellectual conservatives and hardly anywhere else. Frank Meyer is not a household name like William F. Buckley Jr., or even one of those “I think I’ve heard of him” names like Russell Kirk, in part because Meyer was more of a behind-the-scenes operator who wrote primarily for magazines and only authored two books. One of those books, though, made an impression on people who made an impression – among them a future US president.

Of that volume, In Defense of Freedom (1962), Flynn writes, “Everyone who read one of the three thousand copies of the initial printing seemingly later ran for office or started a political club or founded a magazine.” He compares this to the under-the-radar influence of the “meagerly selling” rock album The Velvet Underground and Nico, which inspired a generation of misfits to take up guitars and form bands. This is just one of several offbeat analogies that might perplex some conservative readers but is nevertheless spot-on.

In Flynn’s hands, the right wing – or at least the agenda-setting group of agitators, carousers and intellectual misfits of the 1950s and 1960s he chronicles here – is indeed fun, and a lot of other things besides. What it’s not is the humorless, rigid-minded WASP scolds typically featured in media portrayals of the era. (Even if the inspirations for those stereotypes – The House Un-American Activities Committee and the John Birch Society – were real and have an important role in Flynn’s narrative.)

If Meyer didn’t ‘invent’ conservatism he at least developed it into the form that the wider world came to recognize

The book is a wonder, in part due to Flynn’s deft balancing of more colorful elements with the quieter but no less dramatic interplay of Big Ideas that consumed Meyer and his cohort. And Meyer’s backstory, illuminated by a cache of previously lost papers Flynn uncovered “in an old soda warehouse” in 2021, is nothing short of astonishing – in fact it’s the stuff of Coen brothers and Christopher Nolan films.

Prior to becoming the architect of “fusionist” conservatism – the blending of libertarianism, traditionalism and anti-communism that propelled Ronald Reagan to the White House – Meyer was a strident communist and free-love enthusiast loudly rallying for the Stalinist cause in the 1930s at Oxford University and, later, the London School of Economics. His efforts to organize a communist presence on UK campuses were so successful and so disruptive that he was ultimately expelled from LSE and deported from the country for being a foreign agitator. (One of Flynn’s many revelations is that, amid his frenetic activism, Meyer romanced Sheila MacDonald, prime minister Ramsay MacDonald’s daughter.)

In the US he picked up right where he left off, working diligently on behalf of the Communist party USA. A stint in the army, where he was startled to discover that the American proletariat was actually not sympathetic to Marx, and a reading of Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom shattered the foundations of his belief system; which had previously proven robust enough to withstand the movement’s whiplash-inducing shift from anti-fascism (Spanish Civil War era) to fascism-friendly (during the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact) to anti-fascism once again (after Hitler’s invasion of Russia). His disillusionment sent him scrambling for a new all-encompassing system – a new meaning of life.

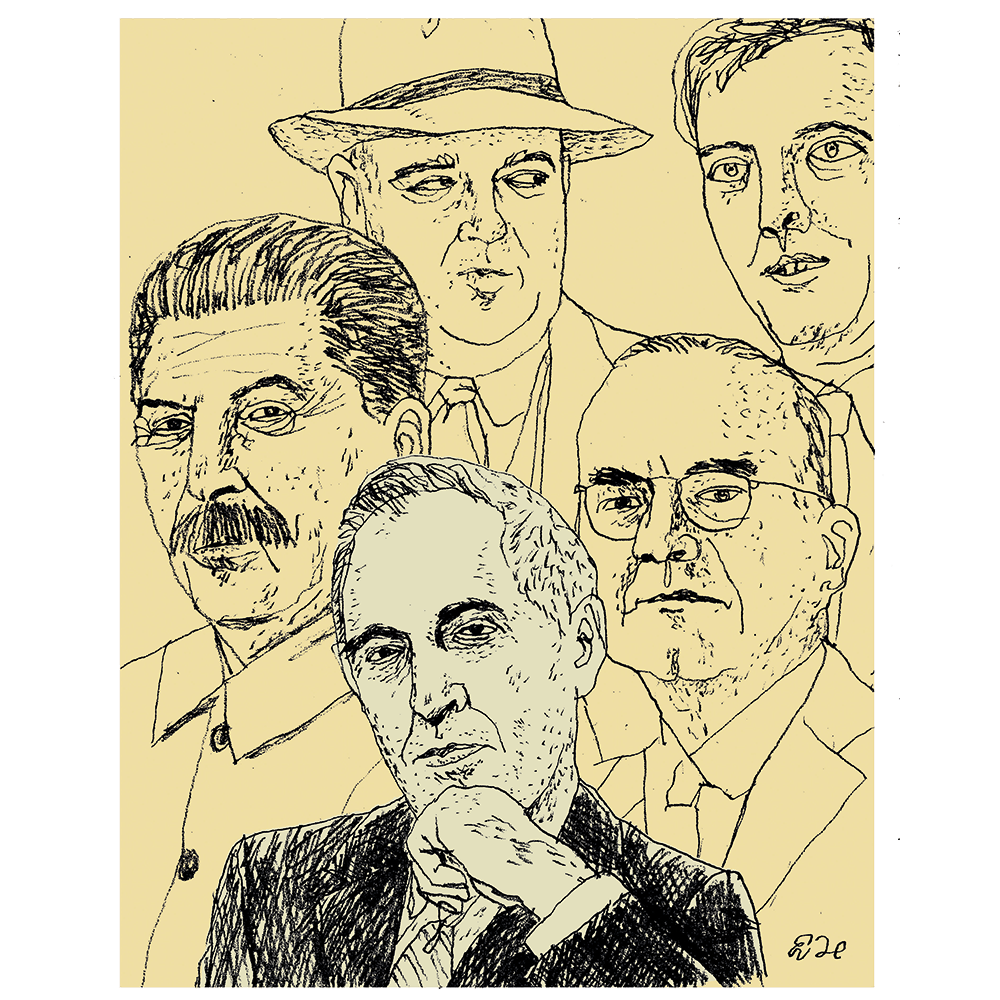

That he ultimately landed in the camp of his previous system’s enemy and insinuated himself within the new milieu as if he had always been there invites admiration for Meyer’s chutzpah. It also indicates that the right of the 1950s was a more tolerant environment than is generally perceived. Alongside Meyer, fellow National Review first-wavers Willi Schlamm, Whittaker Chambers and James Burnham were all former communists. Flynn speculates, with some foundation, that Burnham and Meyer’s prolonged feud at National Review had its antecedent in their oppositional roles as Trotskyist and Stalinist back in their communist days. Similarly, the former purge-friendly Meyer enshrined absolutes and purged heretics (though usually obliquely) in his “Principles and Heresies” column at the magazine.

“Meyer, though, contained multitudes,” as Flynn puts it. The man who could be fractious when he editorialized was responsible for an innovation – fusionism – that brought the hitherto squabbling factions of the right together and kept them in a productive partnership for decades. If he did not quite “invent” conservatism, as the book’s title provocatively suggests, he at least developed it into the form that the wider world came to recognize.

“Ultimately,” Flynn writes, “the Big Idea united the right. The competing partisans, of freedom and individualism on the one hand and of order and virtue on the other, saw in fusionism compelling reasons to reconcile their interests.”

Do we think of Meyer as a conservative simply because he was of that orientation when he died?

There is another aspect of Meyer’s legacy that is less known than his shaping of conservatism, but nearly as significant: As the longstanding editor of National Review’s “Books, Arts and Manners” section – the literary back-end of the magazine – he oversaw a stable of talent that included such future luminaries as Joan Didion, Arlene Croce, Garry Wills, Hugh Kenner, John Gregory Dunne and Theodore Sturgeon. Surprisingly, the ideologue had a keen eye for ideology-transcending talent and a masterly ability to unite writer and subject. The result, in Flynn’s estimation, was “the best review section in America.” For Didion especially, this was a crucial early platform. Flynn again quotes Parmentel (who introduced Didion to Meyer): “Frank deserves the lion’s share of the credit for the discovery, encouragement and development of Joan Didion.” In his role as literary editor, Meyer functioned more as a director than a journalist. The bulk of the editing attributed to him was performed by his wife Elsie, an unsung hero of the magazine’s story and an equal partner in Meyer’s crusade of ideas. She was as quiet and low-key as her husband was outspoken and assertive and is posthumously elevated, at long last, to a co-starring role in this biography.

In examining Meyer’s life in full, any sensible reader will wonder how seriously to take a man who argued so convincingly for two opposing sides. Meyer was so persuasive as a communist, for instance, that he inspired a protégé to fight and ultimately die in the Spanish Civil War; he later became an equally strong advocate for America’s involvement in Vietnam, though his libertarianism compelled him to oppose the draft. On this nagging question of authenticity, Flynn quotes a letter from Theodore Sturgeon to fellow sci-fi writer Robert A. Heinlein. “Now it is obvious that (Meyer) has been looking all his life for a womb to crawl into equipped with a framed glazed set of All the Answers nailed to the warm wall like motel rules,” Sturgeon wrote. “In his current activity he exudes confidence in his discovery at long last of The Way. He is of course not capable of realizing that he must have been just as sure as this when he discovered the Christian Church and the Communist party, and that by this man’s racing form you can bet he’s still a transient.”

It’s tempting to take Sturgeon’s view, which would accord with human nature. Do we think of Meyer as a conservative simply because he was of that orientation when he met his untimely death, at 62, from lung cancer in 1972? It’s impossible to say where he might have gone from there, but my feeling is that he would have held fast to his philosophy because fusionism possessed an elasticity that was missing from his previous “isms.” As Flynn notes, Meyer was able to lean into the libertarian side of fusionism during the more constrained early 1960s, then shift to an emphasis on order when the world around him went haywire at the close of the decade. Both positions were consistent with the message of In Defense of Freedom – a book whose universality has allowed its ideas to be transferable from generation to generation.

The Man Who Invented Conservatism is the kind of book Meyer could never have written. It is a book about ideas – enthrallingly so. But even more, it is a book about people and their beautiful, messy entanglements. It is about the reasons friends fall in and out of love with each other – and the things they are willing to fight and die for. Daniel Flynn, who has always been a witty and engaging writer, explodes into Technicolor here, with his trademark lean style deepening over the course of the book into an expansive, multifaceted perspective that is as big as its subject’s inner universe but somehow never ponderous, and never, ever boring. This is, simply put, the best biography I have read in years.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 15, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply