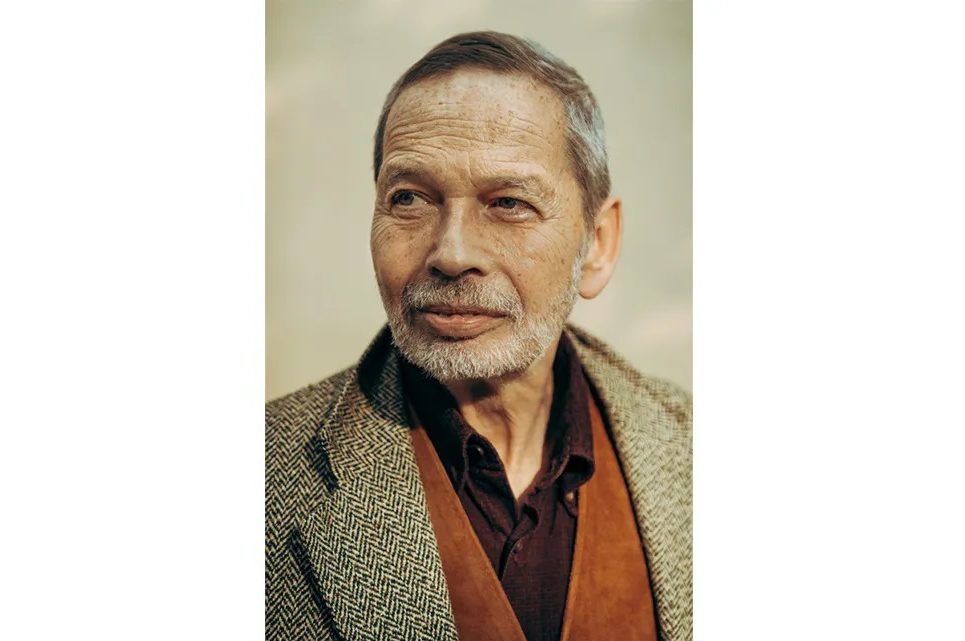

For many years the academic sociologist Frank Furedi has been among the strongest conservative voices in the front line of the culture wars. The target of his latest book is the systematic campaign to discredit the history of the West in the interest of a modern political agenda. The vandalizing of statues, the “decolonization” of institutions and curricula, the recasting of museums and the rearrangement of libraries are all symptoms of something more fundamental. Furedi argues that historical memory is the foundation of western identity and culture. The object of the campaigners is to discredit the West’s ideals and achievements. The result has been to persuade a generation of young people that our history and identity is something to be ashamed of and to dissolve the bonds of shared experience which make us a community.

The War Against the Past is an important book, which chronicles more fully than any other work that I know the gradual development of this rage against the past. It suffers from two main flaws. One is that Furedi is too angry to understand the mentality of those whom he is criticizing. The other is that he tends to go off-piste to pursue other targets, such as gender-neutral vocabulary, trans ideology or dogmatic modernism, none of which has much to do with the discrediting of western culture.

As the campaigners see it, the object of their war against the past is to redress perceived inequalities, mainly of race, which they blame on the West’s sense of its own moral and cultural superiority. This, they argue, has marginalized racial minorities and whole nations outside Europe and America whose histories are equally valid but commonly ignored. In the process, their distinct identity has been suppressed. Slavery and colonialism, as the campaigners see it, are not just historical phenomena but symptoms of underlying attitudes whose persistence is held to be the main obstacle to the proper recognition of marginalized groups. Western societies must therefore be made to “confront” these aspects of their past and feel suitably ashamed of them.

The attachment of historians to present values is not always objectionable. They naturally interest themselves in subjects such as gender and ethnicity which reflect modern concerns. Their views about slavery, torture or cannibalism inevitably reflect their own moral standards rather than those of the people who once engaged in these practices. The real objection to what conservatives call “presentism” is not that it is unpatriotic or anti-western, but that it often relies on bogus methodologies and the tendentious selection of material. The result is a presentation of the past which is fundamentally false. It is exemplified at its extremes by fantasies such as that the original inhabitants of Britain were black or that the Greek philosophers plagiarized their ideas from black Africa.

The study of history is vulnerable to this kind of attack. Historical scholarship involves judicious selection from a vast and usually incomplete body of source material. The significance of any part of this mass of information must depend on the mentality of the age which created it, and not on our own political values. The major threat to historical integrity arises when a modern ideological agenda determines not just the choice of subject but the criteria by which source material is selected and analyzed.

The chief offense against historical truth is to take all the worst features of some historical phenomenon and then serve it up as if it were the whole. This is what has happened to the study of the British Empire. The Jamaican slave plantations, the near-extermination of the indigenous inhabitants of Australia, the Opium Wars and the Amritsar massacre were dark episodes. No one denies that. But Britain’s imperial history cannot be treated as if there were nothing else to it.

Until quite recently, empire was part of the natural order of a world which lacked stable frontiers or any overarching framework of international law. The history of the world is the history of empires. Ancient China, Greece and Rome, the Islamic world, the acquisitive states of precolonial India and Africa were all imperial powers long before the great European empires. Violent migration in search of resources disrupts existing patterns of indigenous life. But it has also served to unlock the riches of the world, to spread technical knowledge and to enlarge cultural horizons, all processes which have immeasurably benefitted mankind.

The British Empire maintained itself by force or the threat of force, as all governments ultimately do. But it brought the rule of law, honest administration, global trade links and economic and technical development long before these things would have been achieved by the rulers that the British displaced, many of whom (such as the Mughal rulers of India) were themselves outsiders just like the British.

All government is light and shade. The liberal instincts which animated British imperialism in its final century were often disappointed by the event. But one area in which those instincts unquestionably prevailed was slavery. Britain has already “confronted” its slaving past. It did so long ago when, against the tide of contemporary opinion, it became the first major power to abolish the slave trade and then slavery itself, before becoming the main agent of its suppression worldwide.

The culture of Europe and of European settlements in the Americas has not always been dominant. It was once outclassed by the civilizations of Asia and the Middle East. But it is silly to deny that in the two centuries before World War Two Europe was culturally, technically and economically the most creative region of the world and the source of most things that have made it a better place.

Does it matter that large numbers of race-obsessed intellectuals wish to discredit its legacy in ways that have very little basis in historical truth? Furedi is surely right to point to historic memory as the key to the identity of any coherent community. Nations exist because there is a sense of solidarity among their populations, of which consciousness of their past is a major component. Social and political institutions only work if people identify themselves with the wider society to which they belong. The fragmentation of a society’s historic identity undermines the solidarities that bind it together. In the process, it also impedes the integration of ethnic minorities and creates artificial grievances which generate racial tensions. The problem is aggravated by the intolerant and polemical tone that characterizes much of what is written and spoken about the past.

Today, an older generation can laugh off the eccentricities of this movement. But to a younger age group they are not eccentricities. They are all that are being taught. A poll conducted in 2022 found that most eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds thought that Britain was “founded on racism,” a view shared by no other age group. These young people are the future. “Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past,” ran the slogan of the Party in Nineteen Eighty-four, George Orwell’s nightmare vision of a totalitarian world. They called it “reality control.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.