There is no portrait by Alice Neel quite as radical as her own. The artist was one of the first octogenarian women to exhibit a nude of herself with 1980’s “Self-Portrait.” In the painting, Neel grasps her paintbrush and sits exposed at the edge of a blue-and-white striped armchair. There’s no doubt about it; this is a woman of conviction who demands, “Look at me, in all my senescent glory: my silver hair, wrinkled face, sagging breasts, this is a life lived and here are its marks.”

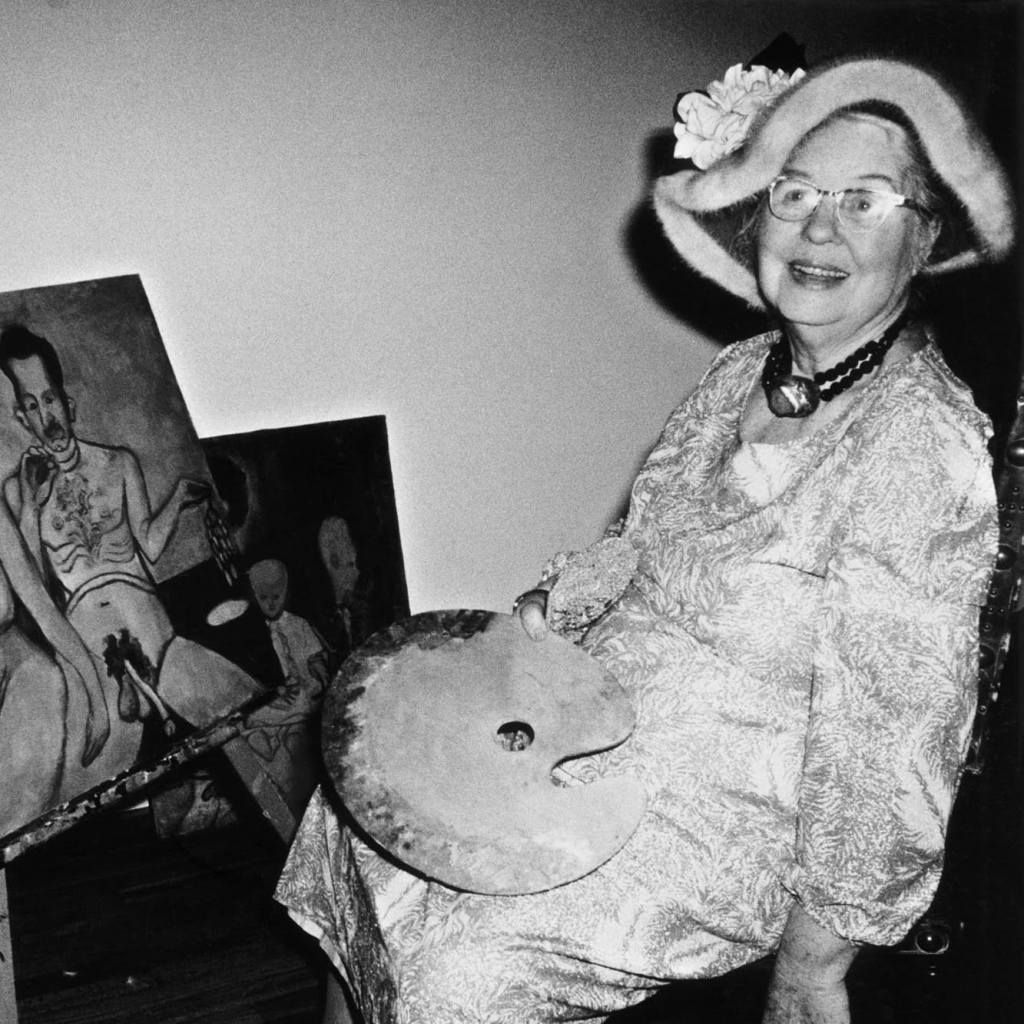

It’s only in the last decade or so that Neel has risen from relative obscurity to be acknowledged as one of the twentieth century’s greatest portraitists. Acclaimed for her gestural, expressive painting style, she used the tools of her trade to become, as she put it, “like Chekhov, a collector of souls.” From the late 1920s until her death in 1984, Neel was a committed socialist, activist and feminist. Her art was often a vehicle for her beliefs, and her canvases became a repository for the lost souls of New York, its bohemians, communists, mothers, children, lovers and outcasts. Neel had a canny ability to capture these peoples’ inner lives, struggles and mannerisms. “If I hadn’t been an artist, I could have been a psychiatrist,” she once remarked.

All who posed for her were subjected to the same scrutiny. It didn’t matter if you were from Spanish Harlem or the Upper East Side, there was no flattery or filter. She employed loose outlines and bold color, stripping away unnecessary detail to focus on her sitters’ true characters, from folded arms to furrowed brows. Take her 1933 portrait of Joe Gould, a Greenwich Village eccentric with an ego so elephantine that Neel drew him with multiple penises. In her celebrated 1970 portrait of Andy Warhol, she cuts through his characteristic bravado to show his vulnerability, painting him shirtless, pallid, sitting with his eyes closed. “To be painted by Miss Neel is not simply the equivalent of a body search,” wrote the New York Times critic John Russell. “It is the equivalent of a body-and-soul search.”

When the major galleries in New York began to splatter their walls with abstract art by Pollock and Rothko, Neel stayed true to her belief that abstraction was anti-human, that it “eliminated people from art.” Despite figuration being deeply unfashionable at the time, Neel remained consistent in her style and subject matter, choosing to shine a light on the full spectrum of humanity. A martyr for the marginalized, her work is imbued with a radical candor, undoubtedly linked to a personal history of struggles, loss and betrayals.

She was born on January 28, 1900, in Merion Square, Pennsylvania. Shortly after her birth, her eldest brother died of diphtheria. After graduating from high school, she began taking art classes at night while working as a secretary. Neel’s parents did not understand her artistic ambitions. “I don’t know what you expect to do in the world,” her mother once told her. “You’re only a girl.”

Lack of parental support failed to deter her. “I’ll show her,” she said. “I’ll show everybody.” With the help of scholarships and her savings, in 1921 she enrolled in the Fine Art program at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, deliberately choosing to attend an all-girls school to resist the distraction of the opposite sex.

It didn’t last long. Enter the aristocratic Cuban painter Carlos Enríquez. The first of a string of Latin lovers, Enríquez married her within the year and the couple moved to Cuba. Here, she was embraced by the Cuban avant-garde and became politicized by local conditions, leading to her lifelong communist sympathies. By the end of 1926, their first child, Santillana, was born, but tragically died of diphtheria before her first birthday. Neel gave birth the following year to another daughter, Isabetta. The couple moved back to New York, where Neel would remain for the rest of her life, the city and its inhabitants becoming the artist’s most constant subjects.

Neel’s fortunes then took a dreadful turn for the worse. Enríquez left for Cuba, taking Isabetta with him. Devastated by the death of one daughter and the separation from another, she had a nervous breakdown, twice attempting suicide (once by eating glass) before being committed to a sanitorium. Neel then had an affair with Kenneth Doolittle, a heroin addict and sailor who moved with her to Greenwich Village to associate with fellow leftist radicals and artists; he encouraged her to join the Communist Party in 1935. In 1934, in a fit of jealous rage, Doolittle burned her drawings and fifty oil paintings; singe marks can still be seen in her portrait of Joe Gould.

In spite of the grief, fire and fury, Neel blazed on. Between 1933 and 1943, she sold a few paintings and received fund- ing for documenting the “American scene” for the Works Progress Administration, one of FDR’s New Deal initiatives. Once that income dried up, she relied on welfare to make ends meet. She began painting labor strikes, protests and other politically charged scenes to align herself with those fighting for equality and workers’ rights during the Great Depression.

After moving to Spanish Harlem, she began to paint scenes of its poverty-stricken community. She worked from the confines of a railroad apartment, looking after two young children, Richard (her son with the musician José Santiago Negrón) and Hartley (her son with the photographer and film critic Sam Brody) as a single mother with limited funds and space.

Coming face to face with the hunger, illiteracy and unemployment that plagued Spanish Harlem inspired Neel to give humanity to people’s suffering through portraiture. In 1940’s “T.B. Harlem,” we look upon a bedbound Carlos Negrón, the brother of her then-lover José. In the painting, Negrón gazes out, holding a hand to the bandage which covers his surgical wound. As with all her portraits, Neel draws attention to a pressing contemporary social issue while maintaining the sitter’s dignity. She blurs the background so we can concentrate on Negrón’s suffering, his hand placed in the style of a martyred Christ.

In 1962, Neel moved from East to West Harlem, and began to work on a larger scale, with bolder color. It was also during this time she began producing pregnant nudes, a rarity in Western art. The artist’s paintings of mothers were equally as radical, dispensing with beatific Madonna and Child cliché to show instead the psychological strain of caring for children, such as in 1943’s “The Spanish Family,” where a Latina woman sits, exasperated, with her young children. In a later work, 1972’s “Carmen and Judy,” Neel’s former cleaner holds her disabled child, who died shortly after the painting was finished.

Neel discarded the sanitized and domesticated and welcomed unvarnished images of motherhood, tapping into her own eventful experience to show the gamut of feminine emotions. By making women seen, she played a vital role in the feminist art movement, although her relationship with her peers was not without its complications; she particularly resented the clichés about female artists that dominated art criticism.

Whether she liked it or not, it was during the rise of second-wave feminism in the 1960s and 1970s that Neel began to receive widespread recognition for her work. She painted a new generation of female activists and artists leading the women’s movement, as in her portrait of writer Kate Millett featured on the cover of TIME in 1970 and in 1972’s “Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis),” which dramatizes Peslikis’s “unladylike” pose, an arm raised to show her unshaven armpit. The Seventies would be the decade that came to define Neel. Her work was featured in a landmark exhibition, Women Artists 1550-1950, at the Los Angeles Museum of Art and in 1974 she landed her first retrospective at the Whitney Museum. She even won an award from President Carter for her outstanding achievements in art.

Neel’s path to success was long and arduous, paved with heartbreak and poverty. But it was her insider-outsider status as a radical, communist, feminist and mother that shaped her artistic vision and ultimately won her acclaim. Not only was the artist a chronicler of people’s souls, she served as a visual archivist of twentieth-century New York. From her Lowry-like paintings during the Depression to her portraits of those in the queer community (many of whom would fall victim to HIV/AIDS), she depicted people’s plights sympathetically but never sentimentally and worked to give them visibility.

It feels appropriate that “Self-Portrait” was one of Neel’s last works. She sits in the chair many subjects had sat in before as if to tell us: “We are all bodies of history, wrinkled by time.” The painting may have been a memento mori, but Neel’s artistic reputation shows no signs of expiring.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply