A few years ago, I was sitting in the London Library researching a book about blind people across the ages. As a semi-blind person myself, I sighed at the lack of women, other than the endlessly chipper Helen Keller, who never had a bad day. Ever.

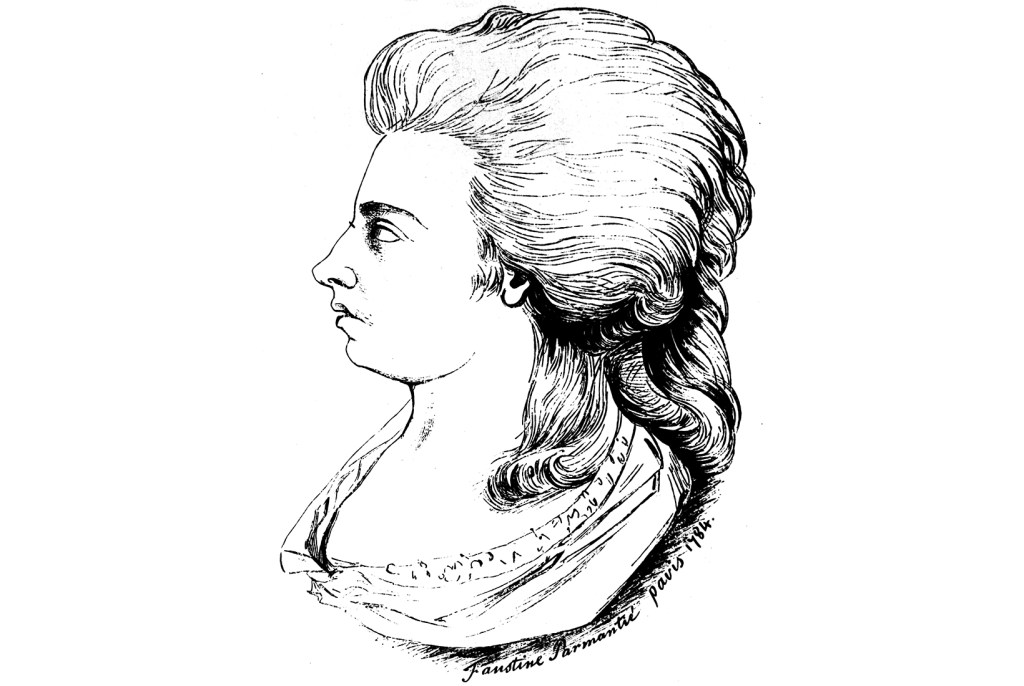

My sister, however, drew my attention to a two-line wiki entry for the 18th-century composer, singer and professor — and darling of the Viennese musical court — Maria Theresia von Paradis (1759–1824). Ten years passed, and after many hours of research in libraries and chats with music scholars, we now find ourselves — to our utter amazement — co-writing a chamber opera about her life. Working alongside the playwright Nicola Werenowska and Graeae theater director Jenny Sealey, and with glorious music by composer Errollyn Wallen, we have reframed her life and created The Paradis Files, a piece dedicated to giving Maria Theresia her own voice.

Paradis’s story has always struck me as intriguing not only because of her talent, but also because we know so little about her. Indeed, our girl seems to have stayed on the hillside of history despite her popularity in her day (the Times of London called her ‘the Blind Enchantress’) and despite the fact that she was deeply respected by her musical peers. Mozart, Salieri and Haydn all composed for her — and most likely shagged her. Her playing was considered exceptional and was known in all the royal courts of Europe. She went on tour from Vienna to London, via Paris, where she met her childhood playmate Marie Antoinette, and played with George III at Buckingham House. By the time she was in her thirties, she had started the first school for blind musicians in Vienna, which ran itself entirely by subscription and from the funds raised at the Sunday concerts at which she and her students performed.

Madame von Paradis was also, alongside her stellar musicianship, an inventor, creating different-shaped playing cards for blind people so she could join in at the card tables at court. With an engineer and architects, she designed raised maps made of pâpier-maché as well as silken cords with different knots that she draped across her lap so she could discreetly recall key and time changes while playing. She died leaving enough money in the bank to support the school for a century afterwards, and unlike Mozart, who was buried in a pauper’s grave, she was laid to rest in a beautiful family mausoleum in Vienna. The catalogues that existed at her death show that she had written at least five operas, two cantatas, 15 keyboard works, several songs and a piano trio. As of 2020, only 20 percent of her work survives, although I suspect much of it is hiding in a castle somewhere and we simply haven’t found it.

So why don’t we know her name and music and, perhaps more importantly, should we? Maybe she was not as gifted as the other great female composers of the early 19th century such as Clara Schumann, Louise Farrenc and Fanny Mendelssohn. The fact that so many works are lost doesn’t help. And the one hit to survive, ‘Sicilienne’, which every cellist performs — it was played beautifully by Sheku Kanneh-Mason at Harry and Meghan’s wedding in 2018 — might not even have been composed by Paradis.

Another reason she doesn’t form part of the 18th-century musical canon lies with the cultural context in which Paradis lived and worked. Music and composition were domestic occupations in 18th-century Vienna, and women’s relationship to music found its expression mainly in the salons of home and court, rather than in the public arena. Second, according to Dr Geoffrey Govier, professor of fortepiano at the Royal College of Music, public success, and the longevity of your music, would very much depend on your music being printed and republished. We simply don’t know how much of Paradis’s music was printed and shared, and thus known about beyond her own circles, though we have found a few of her youthful compositions, which are very charming.

[special_offer]

I suspect, too, that Maria Theresia was ignored because of her blindness. This was, for the Enlightenment, often interpreted as a catastrophe and in need of fixing. This was very much the policy of Maria Theresia’s family, who gave permission for her to receive electrolysis on her eyeballs, for her head to be encased in plaster for three months, and for years of purgatives and diuretics. Indeed, most press coverage of her life dealt with her treatment at the hands of Franz Anton Mesmer, the man behind ‘mesmerism’, who took Maria Theresia under his care (he waved magnets and played the glass harmonium to her) and claimed to have cured her in 1777. The story exploded in court and was followed closely by the press. Many medical men applied to meet the young musician to see for themselves. Yet few were granted access as, according to her father, she appeared to have ‘lost’ her talent. Instead, her father wrote, she seemed to stare at the keyboard as if she did not know it.

It was hardly surprising, therefore, that three months after the alleged miracle, her father told the court that she was still blind and had, in fact, never regained her sight. He argued that he had been misled by Mesmer and that his methods were fraudulent. Epistles were published at dawn between Baron von Paradis and Mesmer, and the Austrian medical establishment agreed to investigate Mesmer’s methods. Unable to defend his name, Mesmer fled to Berlin and then to Paris. Maria Theresia, on the other hand, recovered, and started her music school for blind children.

So what does her story tell us? Possibly what is saddest is that, despite her immense talent, Maria Theresia’s own voice is never heard. What traces remain are written by those men who trained her, treated her or managed her life. I like to imagine that she might have been quite a stroppy soul who ate cream puffs as she composed. A few famous writers have rediscovered her, including Julian Barnes in his short story ‘Harmony’, and the musician Claudia Stevens in Playing Paradis. But what is striking about these is how they focus on her medical treatment under Mesmer rather than on her immensely successful musical career. While blindness no doubt played a key part in shaping her life, it also influenced how people treated her in the 18th century and beyond. Perhaps with a bit more excavation, and reframing, and by telling her story from her perspective, it might be possible to place Paradis upon the musical throne on which she so rightly belongs.

Watch

The Making of Paradis, a documentary about the opera The Paradis Files, on September 25 at 2 p.m. ET at the Tête à Tête opera festival’s website. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.