Hollywood is America’s greatest export. Yet most museums either fixate on the industry’s tawdriness, as with the Hollywood Museum’s preservation of Marilyn Monroe’s pill bottle, or prioritize indie films over the artistic yet popular movies of Old Hollywood. MoMa’s film program can get so lost in Sundance obscurity that you wouldn’t know movies were a popular art form. When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences — aka the group that gives out the Oscars — opened the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles, Americans hoped an intuition would finally document the products, people and dreams pumped out of La La Land. But the space was so preoccupied with twenty-first-century politics that it failed to honor the Jewish immigrants who built the damn town. It was a waste. For some reason, curators seem unable to give Hollywood its due.

And so when the Boca Raton Museum of Art invites me to their new exhibit, Art of the Hollywood Backdrop, I roll my eyes. The press release argues that backdrops are serious works of art, as essential to film history as the directors, actors and writers who have become household names. I agree with the sentiment. The thesis stems from the work of co-curator and University of Texas at Austin professor Karen L. Maness, whose seminal history book The Art of the Hollywood Backdrop preserves backdrops from The Wizard of Oz, Cleopatra and other golden-age films. (Full disclosure: I previously worked as a publicist for Maness’s publisher, Regan Arts, after it released Maness’s book.) I’ve been to the Academy Museum, I’ve been to the Hollywood Museum, I’ve even been to a film museum in Berlin — and none of them have given the golden age its due. So why would Boca be any different? After all, outside of Art Basel, which is little more than a touring carnival/nightclub circuit, Florida isn’t exactly known for its art. It’s Disney World and DeSantisland, where families go on vacation and “woke goes to die.” My gut says the exhibit will fail, but I admire Maness’s scholarship, so I decide to give it a shot.

My expectations fall further the second I park my car. Unlike the Academy Museum, which is housed in a grand historic, literally gold, Art Deco building on iconic Wilshire Boulevard, the Boca Raton Museum operates at the end of an outdoor shopping center. The tiny buildings resemble stores in a small town (think: Main Street, USA), but the Starbucks, gift shops, whiffs of suntan lotion and women in gold leggings create the vibe of a mid-budget Florida Hilton.

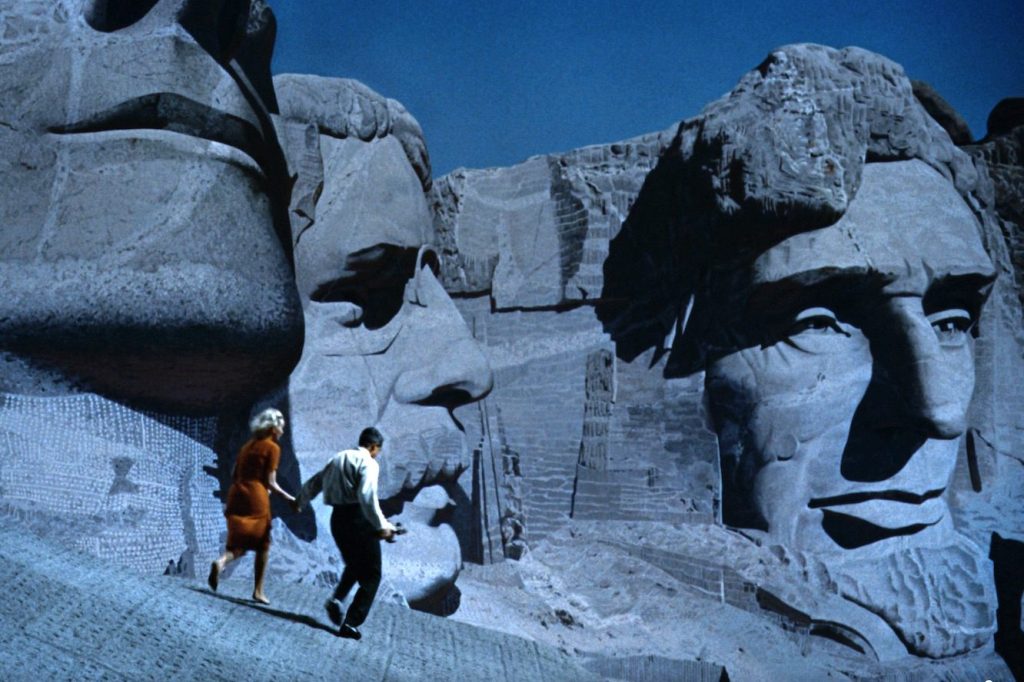

The Jimmy Buffett-meets-Mar-a-Lago energy evaporates the second I enter the museum, confronting a wall-size painting of Mount Rushmore. Abraham Lincoln’s stone eye stares at me from behind a shadow; the rocky texture appears so life-like the painting looks like it could slice my finger. It’s a Hollywood studio backdrop from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1959 MGM classic North by Northwest. I saw a similar backdrop in a tiny room in the Academy Museum, but the small space made the painting feel miniature. Displaying the work in the entryway on a vast wall reveals the shocking size and detail of Hollywood’s backdrops. It also lets me know that Boca hosts a different type of Hollywood exhibit.

Executive director Irvin Lippman isn’t who you would expect to run this museum. He greets me near Lincoln’s eye. With his shiny head and collared shirt, he looks like a veteran of the museum world, and he comes to Boca after a lengthy career at various museums, including in Chicago, where he worked with Richard Avedon.

He’s running the museum in a new moment for Palm Beach art. The Republican enclave is in the midst of an artistic tsunami. Finance tycoon Ken Griffin recently moved his collection from the Art Institute of Chicago to the Norton Museum. (As Vanity Fair reported, you can now see the Rothko that cost Griffin $30 million at the Norton.) Art Palm Beach just merged with the influential LA Art Show. Art is everywhere in Palm Beach right now — and Boca, just down the street, has benefited and grown its collection in the past few years.

Much of the press has associated art in Palm Beach with money, as if it’s an asset more than a piece of culture, but cash doesn’t enter the conversation with Lippman. (Thankfully, neither does dull, nauseating 2023 politics.) Alongside Maness and co-curator Thomas A. Walsh, he’s on a mission to do what he did for Avedon for artists forgotten to Hollywood history.

“[The exhibit is] a way to celebrate artists who never got screen credit,” Lippman says as he leads me past Mount Rushmore and down a hallway with two backdrops dominating each opposing wall. “They credit graphers [in film credits] but not [backdrop] artists.”

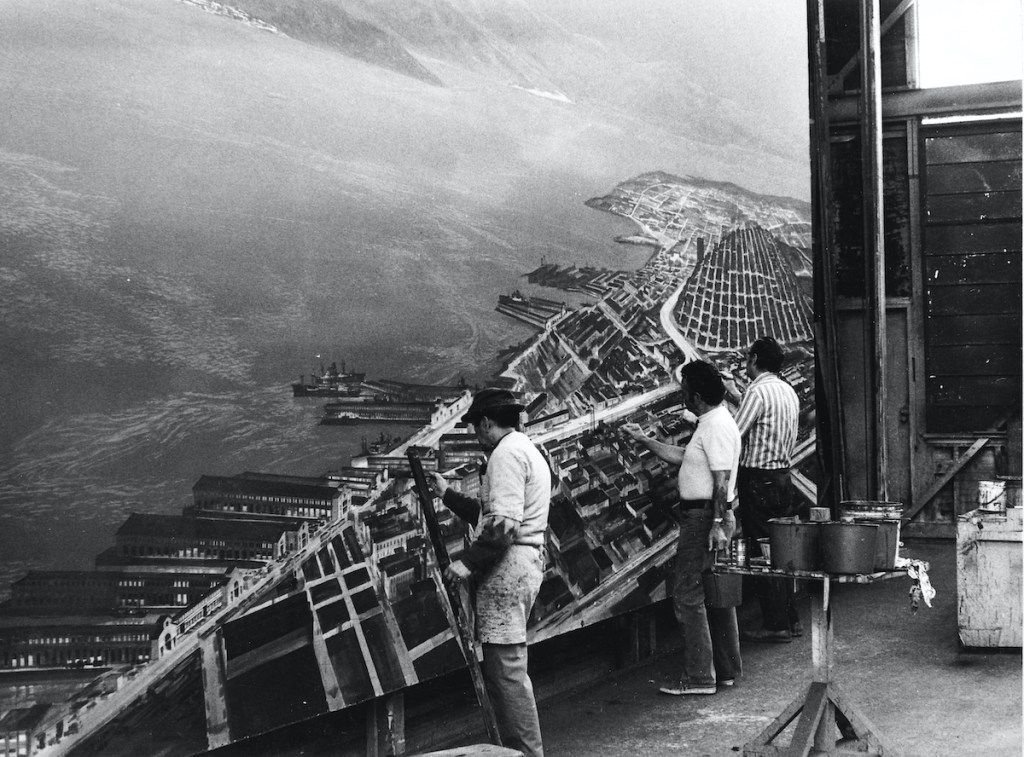

Pointing at a label that lacks a name, Lippman explains that it’s a mystery who painted much of the work on display. According to Lippman, the studios didn’t keep a record of who painted what, and when they were done with a backdrop, they stuffed it in a dank warehouse, where they didn’t even bother to write down what film the painting was used in. Hollywood kept such shoddy records that Maness and co-curator Thomas A. Walsh failed to identify which films some backdrops were painted for. Take the backdrop depicting a lavish staircase. Nobody could identify its origin until a guest recognized the backdrop from a scene in Hitchcock’s Marnie.

This particular painting looks flat. Quite frankly, I’m unimpressed. But Lippman insists it’s magnificent. He encourages me to hold my iPhone camera up to it. Through my camera, the painting gains depth.

It’s only through a camera that you can see the complexity of backdrops. When you see the Jerusalem city painting from Ben-Hur on the wall, it looks like a massive cityscape created as wallpaper for a Cheesecake Factory. A video next to the work explains how cinematographers would change the lighting and angle of the painting, and from different perspectives, the city could look like a small neighborhood or an entire town. I hold up my cell phone, and I experience the same situation: from one angle, I am on a hill overlooking the whole city, from another, Jerusalem appears right behind me. This isn’t wallpaper; it’s genius.

I only can recognize the brilliance because Lippmann, Manness and Walsh encourage guests to participate. Bernard Herrmann’s cinema scores blast through the room (this is not a quiet New York Chelsea gallery). A couch is placed in front of the hallway backdrop used in the “Make ’Em Laugh” number from Singin’ in the Rain, so guests can take selfies and pretend they’re in the Gene Kelly classic. In most museums, selfies, music and overall experiential aspects — think the Ice Cream Museum or those horrific VR Vincent Van Gogh spaces that cost a zillion dollars to enter — feel like horrible children’s playgrounds, but here, in Boca, the experiences help viewers understand the purpose, and more importantly, the beauty, of the art.

This isn’t to say the museum oversells Hollywood. Every backdrop is beautiful, but not every backdrop was hung in a beautiful film. A large-scale tapestry comes from a forgotten 1938 Norma Shearer film. On the wall, it looks like it could come from the Met on Fifth Avenue; in the film, it looks tacky like a Shear flick. Meanwhile, another backdrop hails from the abysmal Fountainhead. Their inclusion shows how Old Hollywood was quite literally a factory, pumping out products… but even a factory can produce art. There are designers at Ford creating cars, and painters recoloring the walls of houses.

Hollywood is all smoke and mirrors — and Lippman wants us to honor the men who cranked the smoke and built the mirrors. In this growing museum, Lippman and his guest curators have done what Hollywood could not. They’ve done the damn thing — by which I mean, they’ve forgotten modern politics and preserved Hollywood art.