To sleep or not to sleep — that is the question the French writer Marie Darrieussecq asks in her latest book, which explores the insomnia that has haunted her for twenty years since the birth of her first child. From that date, she writes, it “has attached itself to me like a small ghost.”

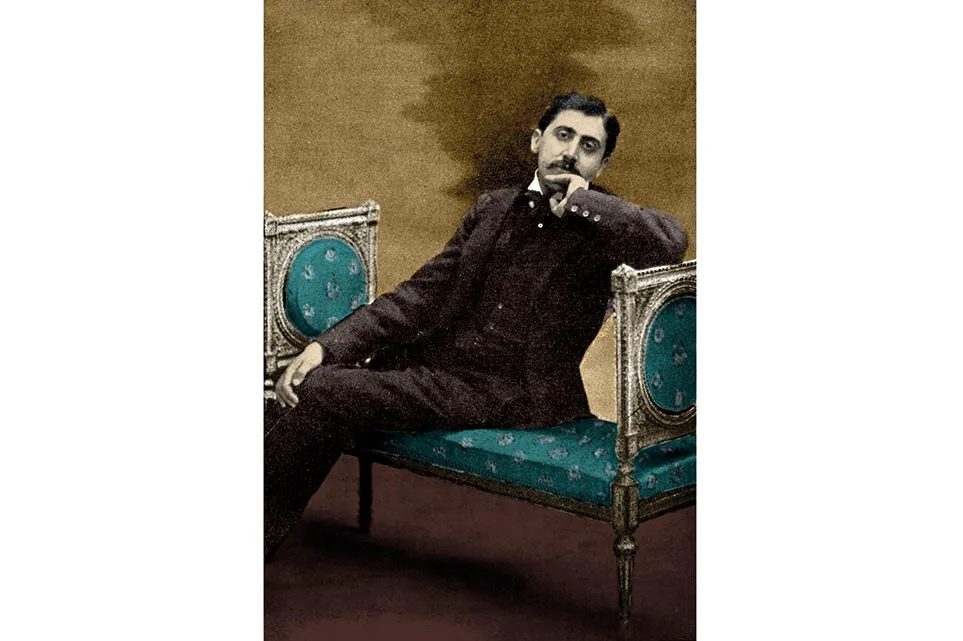

Darrieussecq is best known for her surreal novel Pig Tales (1996), but Sleepless is an account of her search for a cure to insomnia and the solace she finds in discovering writers such as Franz Kafka (“the patron saint of insomnia”), Marcel Proust, Georges Perec, Sylvia Plath, Susan Sontag, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Mahmoud Darwish, Haruki Murakami, Aimé Césaire, Jorge Luis Borges and Tchicaya U Tam’si have all suffered from sans sommeil.

Reading about these “champions of fatigue” gives the distinct impression that to sleep soundly is terribly bourgeois. As Roland Barthes said: “Insomnia is classier than sleep. Only the tragic hero is an insomniac.” The aging Immanuel Kant was “an insomniac, besieged by ghosts” and once cried out: “Don’t switch the light off, Célèste… There’s a big fat woman in the room… a horrible big fat woman in black.”

In the quest for alleviation, Darrieussecq has tried it all — gravity blankets, the Alexander Technique, yoga nidra, cranial osteopathy, drinking alcohol and not drinking alcohol — to no avail. She is candid about her battle with wine and how it became her mandragora: “I had lost the freedom not to drink.” She uses literary medicine — “I’ve tried metaphors” — and real medicine: “I booze on benzodiazepines.” Pills work, but attack her short-term memory, echoing Proust, who complained that sleeping pills “make holes in my brain.”

Darrieussecq enlists the services of a somnologist, who hooks her up to wires to monitor her sleep. The conclusion is that she suffers from hyper-vigilance. “She just needs a shrink!” you cry. Alas, she has tried that and more: as well as being a novelist and journalist, she has practiced as a psychotherapist. Psychoanalysis, she says, saved her life but did nothing to cure the insomnia.

The translation by Penny Hueston is pellucid, with snatches of prose-poetry that evoke the limbo land the sleepless inhabit: “Insomnia is a ravine where those looking for sleep do battle with shadows.” And there are lines bordering on the Buñuelesque: “Insomnia is a folie á deux: a severed head looks at me on the pillow and that head is me.” The book is a treasure trove of literary fragments. One of the solaces of literature is the realization that others in times long gone have felt what we are feeling now. The exiled Ovid wrote: “But I am wakeful, my endless woes are wakeful too.”

Darrieussecq conjures a cultural kaleidoscope, with references to Vishnu, Fight Club, Chernobyl, A Nightmare on Elm Street and the commodification of wakefulness: the dawn of electricity, 24/7 shops and the news cycles that keep us anxious and awake. “There is no escape from the news;” there is “no shelter.” Homer wrote of “Discordia, daughter of the night,” also known as online shopping at the witching hour.

Darrieussecq’s bed becomes a macro-cosmic reflection on all our beds as she riffs on the politics of sharing with a partner and the separation of sex and sleep, wryly adding: “Ulysses managed to sleep without Penelope for a good ten years.”

Sleeplessness spirals out into tales of ghosts, spells, exorcists, shamans, elephants in Gabon high on hallucinogenic bark, curses, amulets, myths, baldachins, rhizomes, Oblomovism, feng shui and etymology: clinophilia (the love of beds); “clinic,” from kline, meaning bed, and “hypnagogic,” meaning “the state just before sleep.”

Darrieussecq suggests that “awake” is a metaphor for consciousness. She is tormented by endangered species and the plight of migrants. It’s no wonder she suffers from insomnia: she is too “awake.” The guardsmen on alert in Rembrandt’s painting “The Night Watch” gets more sleep than she does.

Darrieussecq views the antithesis of insomnia as sleep. She doesn’t consider that the opposite might be oversleeping, a symptom of depression. And when she writes about how Victor Hugo linked lack of sleep to a guilty conscience, she misses one of the greatest quotes of all time from Macbeth: “Methought I heard a voice cry ‘Sleep no more!/ Macbeth does murder sleep.’” Shakespeare, like Proust, affirms that lack of sleep is a form of torture, the latter describing it as a “sort of death.”

Neither does Darrieussecq refer to Plath’s great poem “Insomniac”; and though she mentions Michel de Montaigne, she skips over his essay dedicated to her very subject: “Of Sleep.” What the essay implies is that we are all different. But what neither Montaigne nor Darrieussecq analyze is why some sleep well and others not. According to the NHS, one in three people in the UK suffers from wakefulness, yet the cure is still a mirage. Still, from inside her sleepless world, Darrieussecq shares with us an elegant journey that finds beauty in the despair of insomnia.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.