Evie Wyld’s powerful fourth novel opens from the perspective of Max, a ghost who haunts the south London apartment where he lived with his girlfriend Hannah. A ghost story is new ground for Wyld, the multi-award-winning Anglo-Australian writer, but her signature traits are immediately evident — poetic observations of unusual details; a pervasive sense of grief and palpable trauma, leavened with a wry sense of humor (Max notes his “strong urge to file a complaint” about being a ghost); and an intricate plot that compels readers to delve into complex past events.

As the book progresses, Wyld alternates sections from Max’s perspective, entitled “After,” with others: “Before,” Hannah’s perspective on her life with Max prior to his death; “Then,” describing the events of Hannah’s childhood in rural Australia; and ones that explore various characters’ backstories. As ever, Wyld handles multiple narratives with impressive dexterity, teasing us with opaque details in contemporary chapters that gradually become clear as she drip-feeds us reasons for their resonance in sections set in the past. There’s a deeply satisfying tension in knowing that, as the novel plays out, we will come to understand, for instance, why Hannah is obsessed with ritually preparing coffee she doesn’t drink, why she treasures a cube of green glass, and what’s behind her aversion to goat’s cheese.

The title evokes the echoes that reverberate between the novel’s narratives; but Wyld also specifically anchors “The Echoes” as the name of the area where Hannah grew up. On this land, beside Hannah’s home, there used to be a school for indigenous people, who were forcibly taken from their families, “broken in like horses” and cleansed of their culture. Many schoolchildren were buried in the paddock: “There’s bones all over the place,” says Hannah’s Uncle Tone. Her childhood neighbor, Mr. Manningtree, whose parents started the school, reflects:

The Echoes. His parents thought it was a good name when they moved there and took up all those acres. They thought it represented the countryside, empty and huge, and how their teaching, their edification, would continue on into the future. But in reality, it made a person think of ghosts.

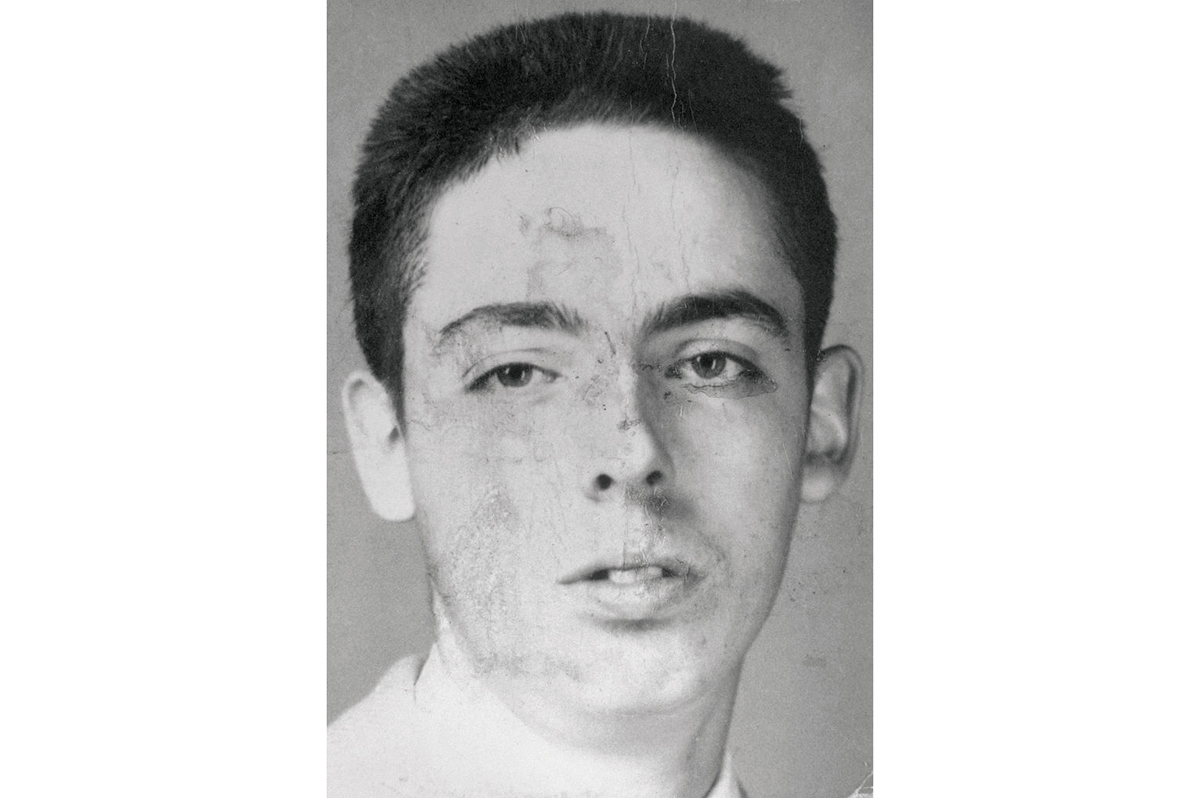

The Echoes is full of ghosts, not just the cat-spooking presence of Max, or the “schoolgirls who haunt the hallway in the dark,” but also — more obliquely — a girl in an old photograph, previous owners of a particular dress, and, devastatingly, the ghosts of violence and trauma passed down the generations.

Hannah struggles to articulate the inherited trauma that’s expressed in her dysfunctional behavior. “I think sometimes silence is better than the wrong person speaking,” she says, in a direct echo of Uncle Tone’s sentiments about acknowledging the crimes inflicted on indigenous people. So who is the right person to speak of past wrongs? In this gripping, upsetting but ultimately hopeful novel, Wyld’s voice rings true.

Leave a Reply