Russia’s war on Ukraine presages a dire future for all of Europe unless Vladimir Putin’s military is decisively defeated. That is the powerful and persuasive argument advanced in Keir Giles’s new book. To appreciate fully the importance of his contentions, you must acknowledge not only Giles’s own status as a supremely well-connected senior fellow at the famed Chatham House think tank in London but even more so the all-star cast of international military luminaries who have publicly endorsed his analysis: the now-retired US generals John Allen and Ben Hodges, UK general David Richards, Australian general Mick Ryan, plus former Estonian president Toomas Hendrik Ilves. Giles’s assertions thus should be taken with the utmost seriousness.

The central element in Giles’s reasoning is his view of Vladimir Putin and today’s Russia. As Ukraine’s struggle for freedom reflects, Putin is “a megalomaniac dictator seeking to expand his territory by force,” someone whose “fascist and nationalist ideology” leads him to “feel that the borders that bound Russia today are incorrect, unjust, and need to be put right” via “a colonialist war to recover lost imperial territory.”

And Ukraine is simply the first entrée on Putin’s territorial menu. Throughout Europe, “2024 saw unprecedented unanimity among intelligence and defense chiefs,” Giles bluntly reports, “that Russia was preparing to attack a NATO state in the near future,” adding “there is no doubt about the intent.” In recent months, Russia has already mounted “a semi-overt campaign of attacks, sabotage, subversion and disruption” against European countries, highlighted of late by how multiple civilian vessels under Russian control have purposely damaged undersea cables in the Baltic. As Giles memorably quotes one top European official privately telling his colleagues, “Russia is at war with us. We can admit that in this room, but we can’t say it outside.”

Russia today has been reduced to a dystopian culture where dishonesty and brutality pervade most aspects of society and even the mildest indications of dissent can land a speaker in prison. “As has happened repeatedly through history, Russians with initiative are using it to leave the country,” as hundreds of thousands already have, “rather than staying behind in the hope of improving it,” Giles sadly notes. Given the breadth of control Putin’s regime now exercises over Russian society, as impressive reporting by the Wall Street Journal’s Matthew Luxmoore has recently illuminated, “there are simply no circumstances — including any conceivable change of leadership — under which Russia would no longer be a threat to Europe,” Giles writes.

“Russia’s ambition for its next war — and hence the future of Europe as a whole — depends on the outcome of its current war” to destroy and subjugate Ukraine. Vladimir Putin — just like the genocidal antisemites who presently control Iran and its terrorist proxies — will not alter his goals simply because the United States now has a president who likely will not suffer from the pathological reluctance to confront Russia that reduced his fearful predecessor’s Ukraine policies to persistent incoherence. “There is no middle ground or partial solution,” Giles argues, “because there’s no scope for compromise with an aggressor that is bent on extermination of its victim.”

Given Russia’s ongoing willingness to send its own soldiers to their deaths in the tens of thousands for marginal gains in occupied eastern Ukraine, the prospect of Putin agreeing to any sort of ceasefire or compromise are presently zero. “Ukraine, through no fault of its own, is the unfortunate focal point of the broader confrontation between Russia and the West,” Giles notes. Thus Ukraine is fighting for Europe, and in light of Russia’s plans for war beyond Ukraine, the West “needs a long-term strategy that recognizes Russia as a determined adversary for the foreseeable future.”

“Russia will remain a threat to Europe until its imperial ambition is broken,” Giles emphasizes — and thus defeat of Russia in Ukraine is essential to prevent a broader, even more disastrous war. Whether in Ukraine or, tragically, elsewhere in eastern or northern Europe, what long-term peace and security require is a clear, unambiguous and undeniable defeat that sets the limits of Russian power and leads to a national reappraisal of the country’s status and role in the world both in the Kremlin and also in Russian society as a whole.

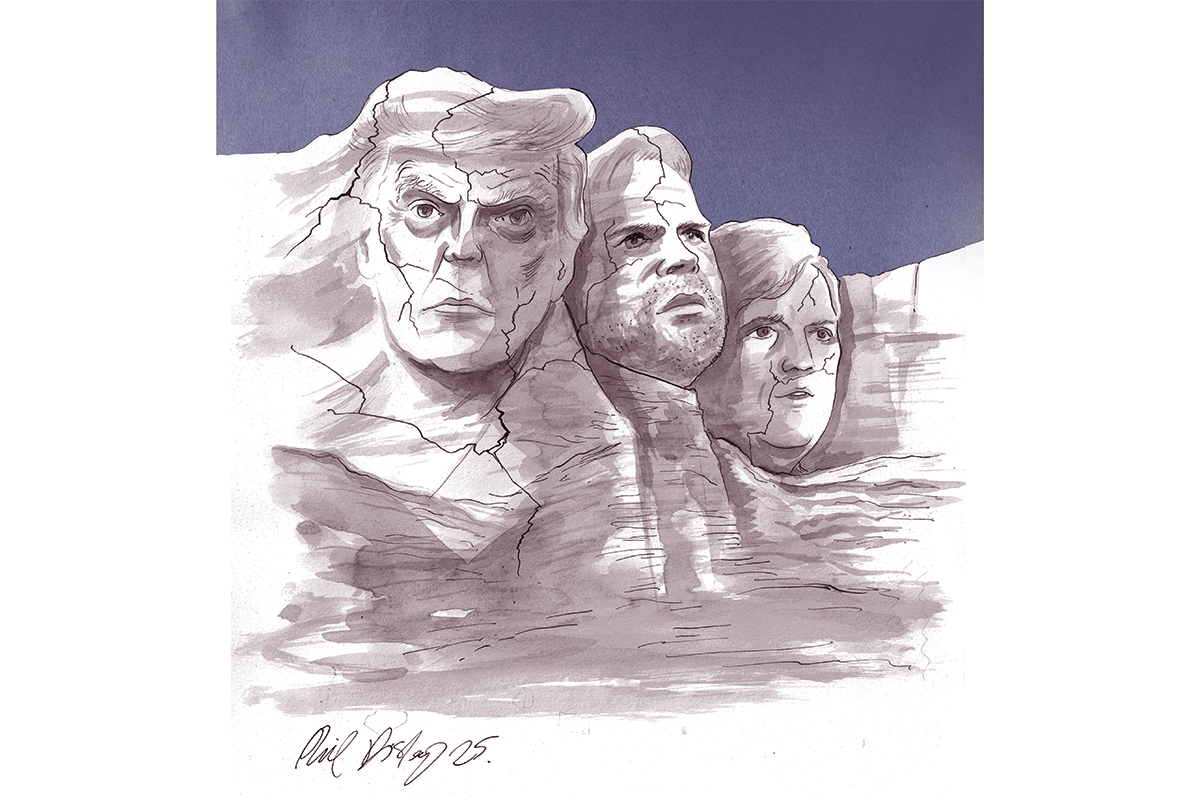

Giles is fiercely critical of Europe’s passive dependence on US leadership of NATO that has led most countries’ own militaries to atrophy. He clearly hopes that the Biden administration’s pusillanimous stance towards Russia will not be an excuse for President Trump failing to reverse it, but Giles’s all too obvious personal loathing for Trump unfortunately leads him to accept at face value some of the most deeply distorted partisan journalism concerning Trump’s supposed affinity for Vladimir Putin. Giles nonetheless hopes for Trump to understand not only that “the great majority of ‘aid to Ukraine’ is spent in the United States and secures American jobs,” but also that “stopping and punishing Russian aggression now is the best way to deter Chinese aggression in the future.”

Yet Giles rightly worries about how dependable US commitment to NATO and the security of its European allies will be going forward. “If the US is not willing to confront Russia over what it has done to Ukraine, how sure can Ukraine’s western neighbors be that when it is their turn, Washington will honor its commitments to them,” he understandably asks. Thus Giles addresses the new reality that European states must look to their own defenses to deter Russia, and he could not be more worried by what he sees.

Notwithstanding the official state of denial reflected by the top European official quoted earlier here, Giles perceives a belated but growing recognition across the continent that immediate action is essential to prevent more widespread war with Russia. Yet he wonders whether Western European leaders possess the political courage required to act decisively in the face of the Russian threat, since “most political leaders west of Warsaw have done an exceptionally poor job of explaining to their electorates what that entails — that huge reinvestment in defense and the industries supporting it is a matter of survival.” Giles worries that “far too many European citizens consider Russia’s war on Ukraine to be a quarrel in a faraway country, between people of whom they know nothing,” yet he emphasizes that the cost of defense is the price that must be paid for sharing a continent with Russia.

Giles concedes that “there’s no doubt that Europe, collectively, is more than capable of dealing with Russia if it develops the collective will to do so,” and he rightly acknowledged that “the clearest recognition of the challenge to Europe’s security from military aggression comes from the frontline states” — Finland, Poland and the three Baltic republics of Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia — whose historical experience of past Russian domination drives national determination to fight rather than submit. Giles recognizes that an eastward shift in the center of gravity of leadership in Europe is overdue, particularly on account of the essential lack of seriousness in Germany about security against external threats.

While France, at least so long as Emmanuel Macron’s term-limited presidency endures, is one of the most useful European contributors to the security of the continent as a whole, other large states such as Italy and Spain, never mind Germany, continue to fall far short of doing what’s necessary. A trio of smaller countries — Denmark, the Netherlands, Czechia, plus the UK — have joined the Baltic states in forthright military support of Ukraine, but front-line Finland, which shares a long border with Russia, is clearly far better prepared to mount a credible defense posture than any other European state. All across the Finns’ deeply unified society, strong defense is understood as a fundamental necessity rather than an option or a luxury.

Close on Finland’s heels is Poland, whose enormously ambitious program of rapid expansion of its military since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 sets an example for NATO allies of what can and must be done. Giles notes that “if the remainder of Europe treated their national security in the way that its easternmost neighbors do, the continent would be vastly safer” than it is today, and he starkly warns that “only a radical transformation of their defenses will render them capable of actually surviving a full-scale war” with Russia. NATO and its European member states will not be ready if they continue to prepare at their current pace.

To this reader, there is no denying Giles’s underlying pessimism about what the future holds. While the most immediate need is for “a concerted effort by the West to fully block Russia’s oil revenues,” which are what allow Putin to fund his war machine, he rightly worries that “ruling out NATO membership for Ukraine” inescapably provides “an incentive for Russia to ensure the conflict” indeed does not end. Giles names neither Hungarian president Viktor Orbán nor American commentator Tucker Carlson, but he rightly rues how there are public figures willing to excuse or applaud Putin now as there were for Hitler and Stalin in the 1930s.

Who Will Defend Europe? deserves a wide readership, not only in western European capitals and parliaments but also at the top reaches of the Trump administration. Giles’s richly documented and persuasively argued case makes all too clear that to bring about Europe’s greatest tragedy since the 1940s, Russia only needs to persuade NATO that the costs of confronting Moscow are unaffordable.

Leave a Reply