We don’t all get to achieve what we could have achieved in life. And yes, I know, so what? Tough luck. Cry me a river, build me a bridge and get over it. But, like it or not, some people really do have the odds stacked more heavily against them than others and yet somehow carry on regardless. In The Secret Painter, the scriptwriter Joe Tucker (Parents, Big Bad World) tells the true story of his Uncle Eric, born in 1932 — an ordinary man who never gave up.

Let’s be honest, The Secret Painter could have been absolutely terrible. I mean, it sounds like a bad idea: a biography of an overlooked northern artist written by his fancy, cosmopolitan, London-living nephew might easily have turned into an irritating meditation on the meaning of Art, and Family, and North versus South and the Class Struggle. It could have been toldas the tale of some misunderstood genius or tragic outsider battling against the establishment. Rather, it’s a plain-speaking, thought-provoking, thoroughly sweet and unassuming story about a plain-speaking, thought-provoking, thoroughly sweet and unassuming working-class man from England’s Warrington, whose delightful, self-defeating ordinariness is what makes the story extraordinary.

“By any conventional measure,” writes the author, “my uncle Eric Tucker achieved nothing in life.” Which is true: he lived with his mother, worked as a laborer, liked a few drinks and putting on a bet and going out at the weekends to the clubs in Manchester. Just, life. But he was also quietly devoted to painting.

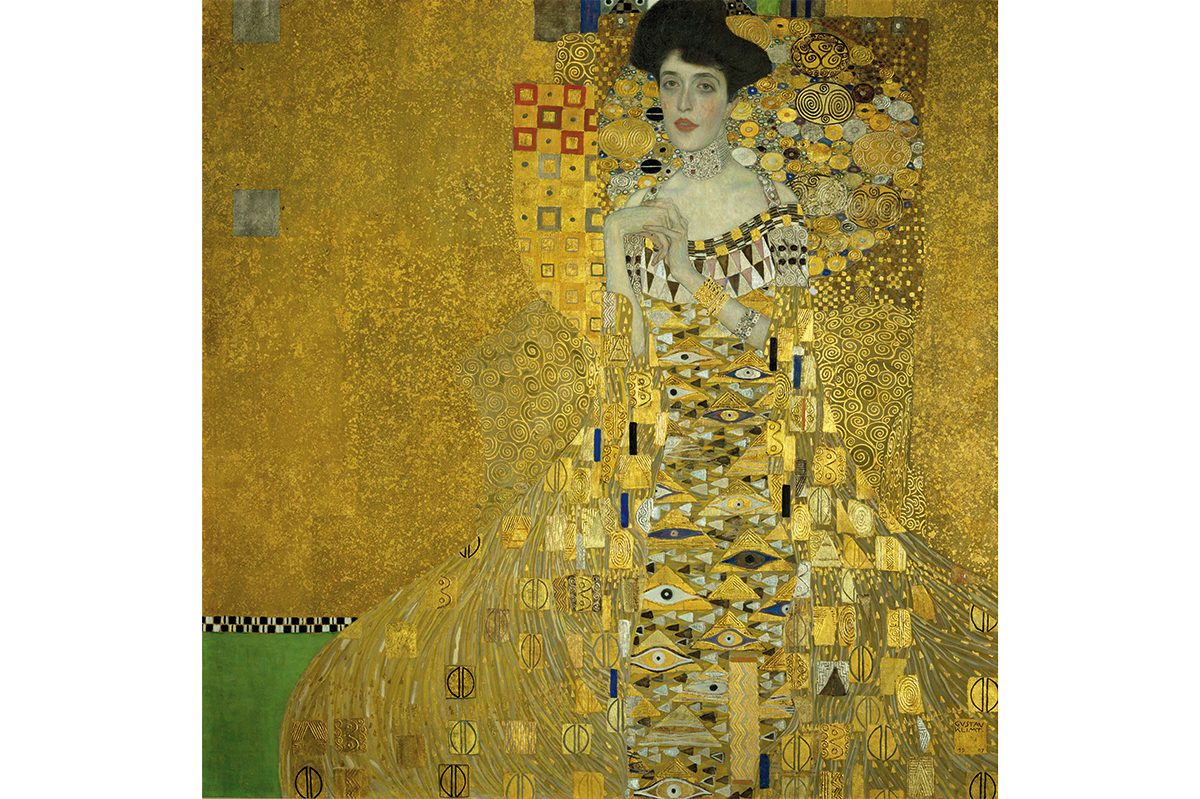

In the modest confines of his mother’s front room, behind a lace curtain and beneath a solitary lightbulb, in the evenings and at weekends, Eric would create his art — not for exhibition, nor in pursuit of fame, but simply because he felt compelled to do so. And he did it consistently for sixty years.

The family, of course, knew about the painting — and occasionally helped him get an exhibition in a gallery. It doesn’t seem to have been lack of talent that kept him from public recognition; rather, an inherent shyness, maybe a touch of cantankerousness and just a general unwillingness to style himself as an artist. He wasn’t interested in self-promotion or in declarations of his ideas and artistic aspirations. As Tucker points out, his uncle never spoke about his work. For Eric, art seems not to have been a career or a means to an end but a deeply personal and solitary act.

Eric would paint not for exhibition, nor in pursuit of fame, but simply because he felt compelled to do so

But art demands to be seen — and so, in the final stages of his life, suffering from a congenital heart condition, Eric asked his brother, Joe’s father, if it might be possible to arrange a solo exhibition. It’s this simple request that sets the stage for The Secret Painter, which follows Tucker’s attempt to bring his uncle’s work to the public eye. It’s an uphill struggle — partly because Eric wasn’t quite odd enough. A piece about him almost featured in the New York Times, but was rejected, not for lack of merit but because Eric didn’t fit the typical narrative of the outsider artist. A true outsider, he was not outsidery enough. “His great victory was that, to a world that told him in innumerable ways that he couldn’t be an artist, he proved that he was, and that he couldn’t not be.”

Eric died in 2018, and we learn just how much of his life was overlooked or dismissed. He seems to have been a man who simply got on with life, with little or no need for validation – or indeed love. There was a brief holiday fling, but otherwise there’s no hint of romance. Eric refused not only to adhere to the expectations of the art world; he refused to adhere to the expectations of any world outside his own.

Tucker is deadpan, witty and tender in his portrayal of his uncle — much like Eric’s art itself, which is a little bit Beryl Cook-y, with perhaps a hint of the Impressionists. He evokes a strong sense of place, bringing to life working-class Manchester and Warrington and Eric’s favorite haunts, including the legendary Tommy Ducks and Liston’s Bar and Yates’s Wine Lodge. He also lovingly describes the delightful characters who populated Eric’s world, including “Buller” Crompton, a man who “used a J-Cloth as a handkerchief.”

The book ultimately suggests that Eric’s greatest artistic achievement was not any single painting but the act of creation itself. In our era, which demands novelty and spectacle even from politicians, Eric’s calm, modest, unwavering commitment to his work offers a poignant reminder of the power of persistence. I really hope Timothy Spall’s agent reads the book: the actor would be perfect casting.