When the news of Gene Hackman’s death at the age of 95 was initially reported, ghoulishness quickly overtook sorrow. The unsolved-crime aspects of his death dominated the coverage.

The actor, his wife Betsy Arakawa and one of their pet dogs were found dead in their New Mexico home in February. They were likely to have died as many as ten days beforehand. The police were swift to suggest that, while initially unfathomable, there were no signs of foul play. Still, this did not stop the usual conspiracy theories, including the indomitable Randy Quaid declaring that Hackman was murdered by the “Hollywood Star Whackers,” who also “got” Heath Ledger and David Carradine.

It remains unclear exactly why the “Hollywood Star Whackers” would wish to kill a nonagenarian who had been living in blameless seclusion since his retirement two decades earlier. There will be plenty of reasons cited in the far-reaching corners of the internet, I’m sure. But these theories are irrelevant when it comes to an assessment of the actor’s work. And it is no exaggeration to suggest that Hackman was the greatest character actor of the past half-century: a versatile performer who could segue between hard-bitten thriller and outrageous comedy with ease. His Marine-trained intensity could be used to denote cold-hearted villainy or all-American righteousness.

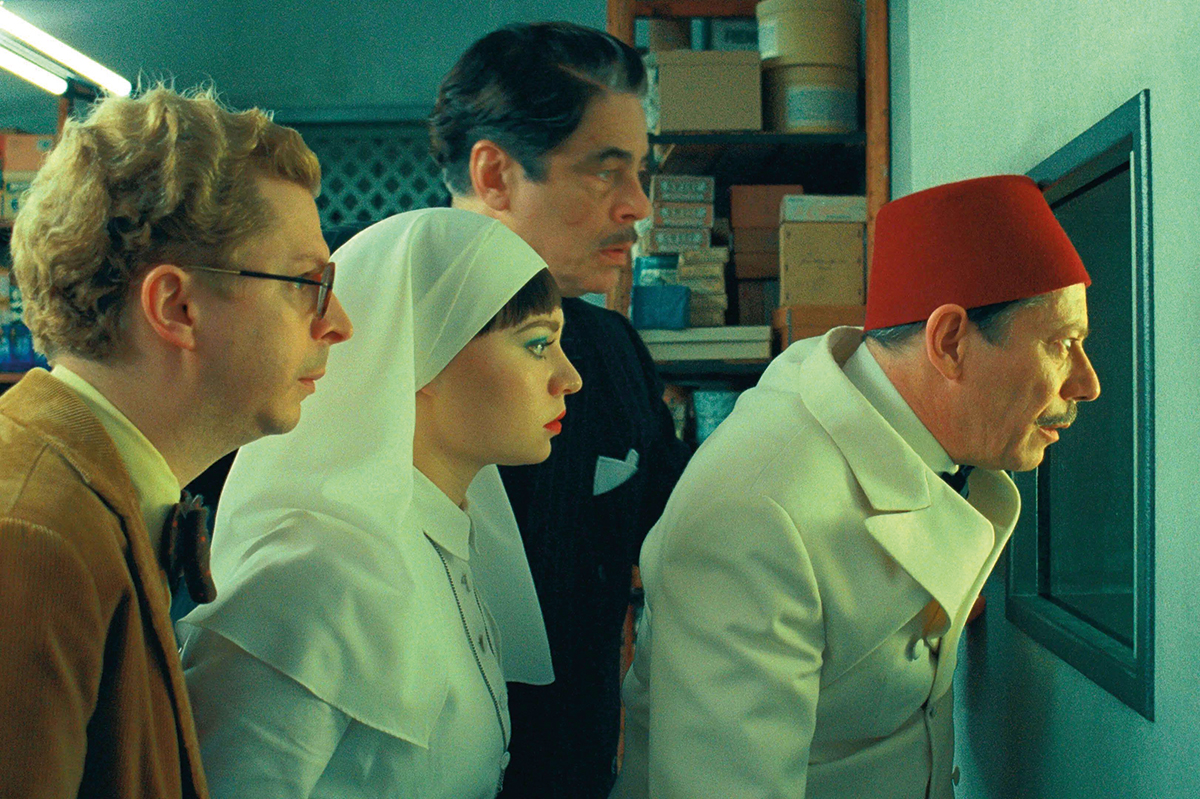

The broad assessment of Hackman’s career since his passing was that he had a quiet 1960s until he broke through with his Oscar-nominated performance as Warren Beatty’s elder brother in Bonnie and Clyde. The decade was followed by a thoroughly successful 1970s, a largely disappointing 1980s, an imperial 1990s and then a largely non-existent 2000s – the exception being his sublime late performance in Wes Anderson’s The Royal Tenenbaums.

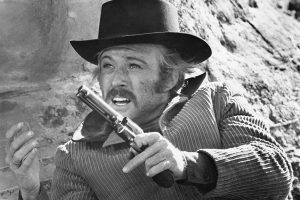

The 1970s were a particularly important period for Hackman. It is hard to think of many other actors who could have appeared in The French Connection (pictured), The Conversation, Night Moves, Superman, Young Frankenstein and The Poseidon Adventure in less than a decade and given wholly distinct but equally brilliant performances in all of them. It is also hard to think of an actor who could have appeared in the notorious 1975 flop Lucky Lady, taken a then-huge$1.3 million salary and walked away from the wreckage wholly unscathed.

The 1980s produced some of Hackman’s most interesting performances, including his brief cameo as a newspaper editor in Beatty’s Reds, his gruffly inspirational coach in the now-classic Hoosiers or, perhaps most intriguing of all, his indulgence of his usually suppressed arthouse side in Nicolas Roeg’s Eureka, in which Hackman plays a gold prospector based on the real-life Sir Harry Oakes. While it is very hard to think of his being actively bad in any film he made, his reprisal of his Lex Luthor role in the dire Superman IV: The Quest for Peace did him no favors whatsoever.

If the 1990s were not as rich a decade for this versatile performer as the 1970s, they were still the years in which he gave many of his most iconic and interesting performances, including the only one on stage as a mature actor, in Mike Nichols’s 1992 staging of Ariel Dorfman’s Death and the Maiden. What he did in cinema was no less compelling. He won an Oscar for his vile but somehow comprehensible sheriff in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, exclaiming “You can’t do this to me! I was building a house!” as he meets his end.

This triggered a range of casting for fascinatingly nuanced villains and antiheroes, from Crimson Tide and The Quick and the Dead to an unbilled performance as a morally compromised lawyer in The Firm. The filmmakers tried to gender-switch and cast his role with Meryl Streep until John Grisham, who wrote the book on which the film was based, said firmly: “I had Gene Hackman in my head while I was writing. Can you not just go out and cast Gene Hackman?” They promptly did, and the result was another magisterial, gently regretful performance that stole the show from the putative star Tom Cruise.

Although Hackman was a consummate professional, he also had a short fuse and frequently clashed with his directors. No clash was bigger than with the relatively untested Anderson when they made The Royal Tenenbaums. The irony of their reported spats was that Hackman gave one of his warmest, wittiest appearances in the film.

In interviews, Hackman never showed Tommy Lee Jones levels of gruff, nor was he a Jeremy Strong-esque figure, talking endlessly about his “process.” Instead, the veteran seemed to talk to the press in much the same way that he would once have dealt with military boot camp: simply get through without taking, or inflicting, any damage.

Still, he let the odd memorable quip fly, telling Premiere in 1990 that “Hollywood is a place where they’ll pay you a thousand dollars for a kiss and fifty cents for your soul.” He observed once: “I don’t read reviews. If I believe the good ones, I have to believe the bad ones, and I’d rather just live in ignorance.”

But perhaps the most profound thing he ever said about acting came after his retirement. In 2008, he said: “I don’t think I’ve ever been comfortable with the idea of being a star. I’m just a working actor who got lucky.” It’s hard not to think we were the lucky ones.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply