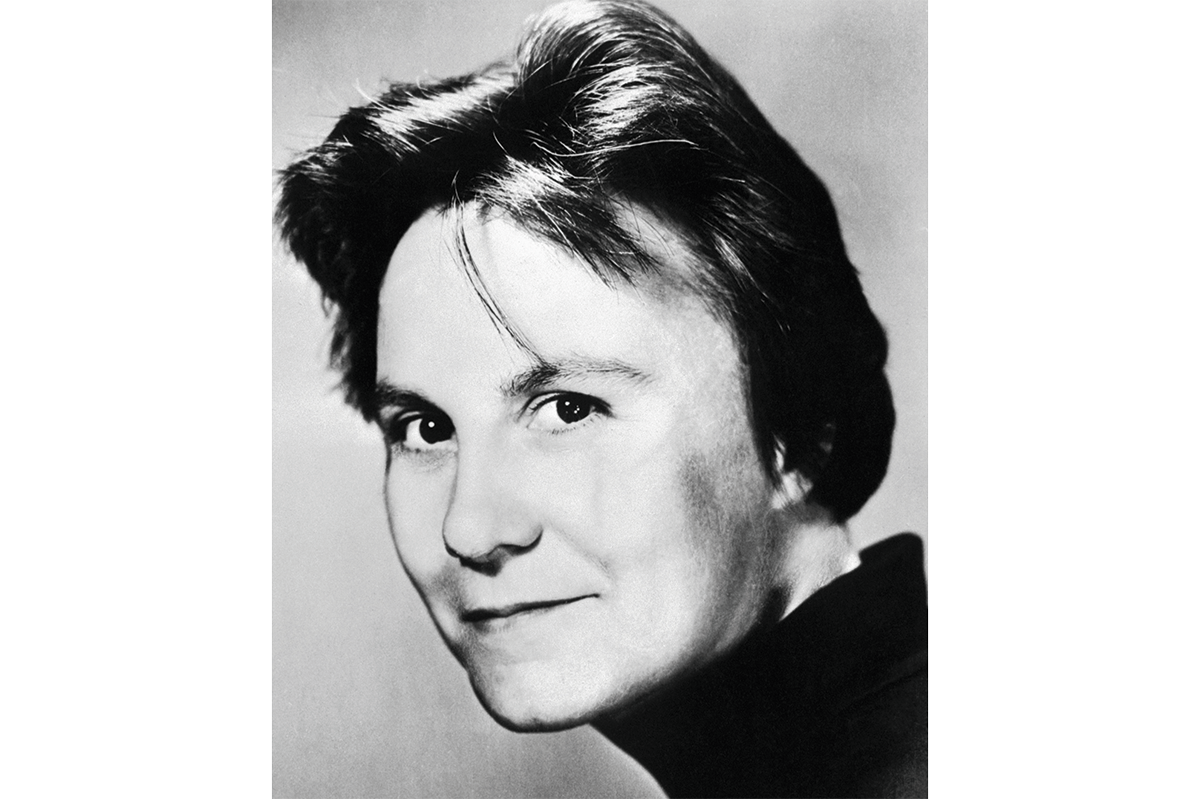

Eliza Clark’s first novel, Boy Parts, centered on a self-destructive woman taking explicit photographs of men. Her second, Penance, was about a journalist constructing a “definitive account” of a seaside murder. Last year she was named one of Granta’s best young novelists; but she has now produced a sadly uneven short story collection, She’s Always Hungry. These eleven tales do not hang together thematically, aside from a broad emphasis on the corporeal.

The good ones are full of brio: “The Shadow Over Little Chitaly” is composed entirely of hilarious reviews of a takeway that offers Chinese food alongside pizza. The feedback is bizarre from the start: the first mentions that the restaurant is 125 miles away and the customer complains that they rang 117 times for a refund. Later commenters are appalled that the Hawaiian pizza contains apple rather than pineapple and that the vegan option is simply a block of uncooked tofu. But the different reactions to the delivery service build into a haunting narrative. Clark plays this absolutely straight, so that at first glance these really could be Just Eat reviews, which is partly what makes it so funny.

Some stories have an implicit feminist intent. “The Problem Solver” cleverly portrays a man complacently strategizing in the aftermath of his friend’s rape, even though she explains: “I don’t want you to do anything. I just wanted to talk about it.” The rape is not described in any detail, so that the focus is squarely on the way members of the victim’s social circle react.

The title story is set in a matriarchal village where “being the mother to a bad man was a worse sin than being daughterless.” How refreshing and clever this is — the old-fashioned setting of a fishing village making it particularly unexpected that the men are subject to systemic repression. Other stories meander less satisfyingly, not least “Extinction Event,” in which a new plant-like species may save humanity.

Faber have taken what is still the relatively unusual step of including a “content guide.” For example, the entry for the penultimate story reads: “‘The King’ contains graphic descriptions of violence and cannibalism, as well as references to racism, sexual violence and apocalyptic themes.” This may be wise — although anyone seeking out an Eliza Clark collection should know what they’re getting.