E.B. White was the author of two delightful children’s books, Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little, perhaps three if you count the lesser known The Trumpet of the Swan. White also wrote a great many not-so-memorable but often anthologized New Yorker and Harper’s essays.

But he is best known to generations of American students as the co-author of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style. The man whose name comes first on that pamphlet-sized compendium of do’s and don’ts, is William Strunk Jr., a Cornell English professor for forty-six years who would have sunk forever in death’s dateless night were it not for White’s sentimental resurrection of him in the pamphlet’s six-page introduction.

What makes Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little work as children’s lit is White’s simple pathos saved from cloying by touches of clever humor:

“Excuse me, sir,” said Stuart to the man who was turning her, “but are you the owner of the schooner Wasp?”

“I am,” replied the man, surprised to be addressed by a mouse in a sailor suit.

Or:

“Charlotte has another cousin who is a balloonist. She stands on her head, lets out a lot of line, and is carried aloft in the wind. Mother, wouldn’t you simply love to do that?”

“Yes, I would come to think of it,” replied Mrs. Arable.

The collision between the fantastic and the ordinary in White’s stories is much of their charm. I would have said that these books are best approached by adults when bedtime approaches for tykes not yet ready to slumber. But my copy of Charlotte’s Web sports an introduction by Kate DiCamillo, one of the finest children’s authors going, who confesses she was thirty-one before she submitted to the spidery book, and then only at the insistence of a writing instructor. So let’s say these books, drenched as they are in sentimentality, have an archness in the telling that adults can savor too.

Would that were true of The Elements of Style. Strunk, the primary author, was a charmless pedant. He compiled critical editions of works by Dryden and James Fennimore Cooper’s Last of the Mohicans, but he was not a practicing writer or an energetic scholar. He was rather a sturdy teacher of English composition at a time when that meant grammatical nicety. He self-published Elements of Style as a classroom handout, nicknamed “the little book.”

As generations of quondam college students know by now, White was one of Strunk’s undergraduate students, and he formed a lifelong attachment to Strunk and his “little book.” Strunk came across to those young men in Ithaca back in the day as the embodiment of a quirky didact. His Great Obsession was concision. If something could be said in ten words, it could no doubt be said better in five. Or three. And if it could be said in three words, the emptiness that followed could be filled by repeating those three words over and over.

Why anyone would think Strunk’s parsimony the key to good writing is a mystery. But White adored Strunk in all his eccentricities, and perhaps channeled him into Charlotte’s brevity. “SOME PIG!” is Charlotte’s silken motto spun over Wilbur’s sty.

In 1959, at the whim of Macmillan Publishing, White wrote an introduction to Strunk’s book and touched up the text enough for the book to become “Strunk and White.” White returned to it in 1971 with a new introduction and a new chapter “An Approach to Style” that adds twenty pages and bulks the whole to seventy-eight pages. It is, let’s say, enough.

Strunk and White is a rule book. Some of the rules are unexceptionable (“Enclose parenthetic expressions between commas”). Some are tedious (“Make the paragraph the unit of composition”). Some are obsolete (“Divide on the vowel”). Some are misleading (“Do not break sentences in two”). And some are infuriating (“Put statements in positive form”).

“Put statements in positive form” means “make definite assertions.” They provide examples of sentences that use negations to nibble away at a statement that the author does not want to assert outright:

“He was not very often on time,” is the bad example, which they correct to “He usually came late.”

The rejected example in classical rhetoric is an instance of litotes. Contrary to their rule, you won’t be sorry if you use it now and then. Ironic understatement by denying the contrary smooths the way in social situations. “He is not spill proof,” has a touch of humanity lacking in, “He’s a slob.” And the same is true in writing. Manners do matter. (Or you might say, “Treat the reader with the same etiquette you would a guest at your dinner table,” but that would be fifteen words, instead of three.)

I suspect Strunk’s (I think it his, not White’s) hostility to litotes is just another instance of his obsession with brevity. It takes more words to express an idea with nuance than it does to declare it outright.

Direct statements certainly have their place and a writer has to know how to use them. But is it wise to tell the novice to throw away perfectly good tools?

Another Strunkian rule is “Use active voice.” He warns — note how his phrasing contradicts “Put statements in positive form” —

“This rule does not, of course, mean that the writer should entirely discard the passive voice, which is convenient and sometimes necessary.”

Nonetheless, legions of English-teacher Javerts have hounded multitudes of student Valjeans to cure them of their passive voice sentences. The active voice was sung to me once on a sleepy afternoon, as it was among her cloudy trophies hung. Active voice usually works, but sometimes a little tactical vagueness sometimes comes in handy. Keats didn’t tell us who hung those melancholy trophies. The Washington Post saved itself the trouble of seeing human agency in “the Waukesha tragedy caused by an SUV.” Alec Baldwin knows something about the gun that was fired on the set of Rust. The cookies were eaten. The bank was robbed. That’s all I’m saying. But in the opening paragraph of White’s introduction to The Elements of Style, three of the four sentences are in passive voice.

The rule that presides over all other rules in Strunk and White is “omit needless words.” For sure, students use a lot of superfluous verbiage. A good instructor comes with a pruning hook. But all too many instructors come with a chainsaw. Ideally, you teach students to love words — to sense their contours, their subtle textures and the meanings inside the meanings. To teach the novice to slash away every needless word is to teach the student to hate the richness of language. Tacitus decried the Romans who plundered the world: “and where they make a desert, they call it peace.” Strunk defoliated English prose and called it “composition.”

Well, let’s be fair. Strunk lived in the age in which Hemingway and other writers were attempting to rid English writing of the mannerisms of late Victorian exposition. They had something to prove and Strunk was there to turn their unadorned sentences into a formal code.

White absorbed the code but violated it freely in his own writing, though it says something that his highest achievements as an author came in the tightly constrained form of talking animal tales for children. His instrument was not really tuned to the complexities of adult reflection. I say that having read through several hundred pages of his adult writing, e.g. “In the matter of girls, I was different from most boys of my age. I admired girls a lot, but they terrified me.”

Teaching college students to write via the hairsplitting rules of Strunk and White is akin to teaching children to swim by lecturing them on hydrology. Granted there may be students who need to be told that water is wet and that you ought not to inhale it. Some rules may be worth setting down. Strunk and White, taken in stride, may do little harm.

The real fault with the book is that so many instructors make so much of it and so many students take it as authoritative. The result is certain prissiness in writing, an unwillingness to discover what a versatile, vigorous sentence can do. Strunk and White set down the conventions of a meticulous editor who has no idea of the subtlety and stealth of imaginative writing that can transform even the most unpromising subject into an entertainment and a feast.

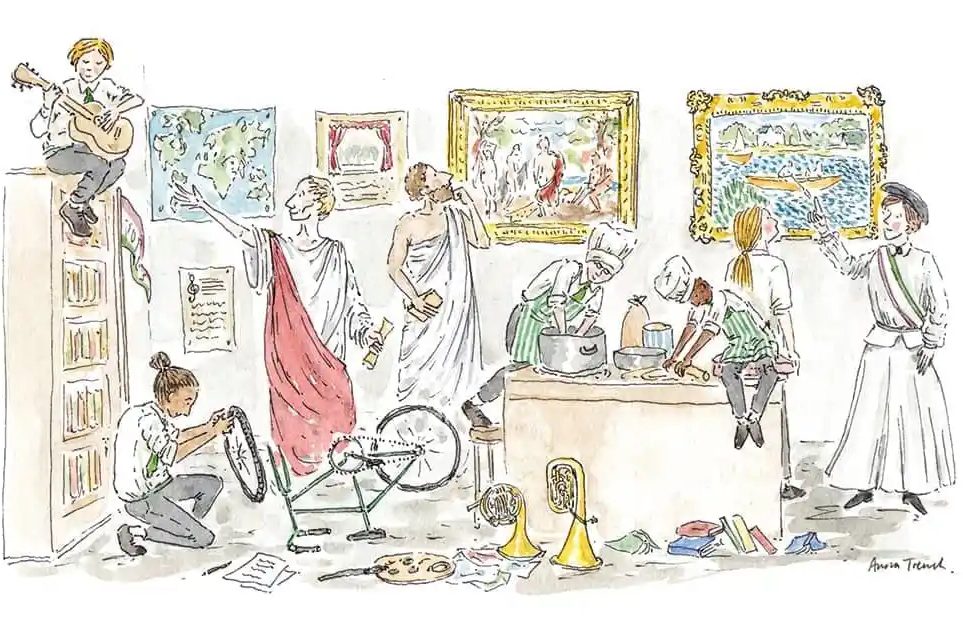

I’ve taught both composition and rhetoric to both undergraduate college students and (separately) prison inmates. I’m not a master of the craft of sprouting the seeds of rhetoric in the dry soil of unlettered students, but I take it as a victory if I free them from the trammels of Strunk and White, whose work offers only the stripped down simplicity of prison bars. The so-called “plain style” Strunk and White promote is a combination of COVID mask and AirPods, muffling the voice and deafening the ear. No wonder so many people turn to telegraphic messages adorned with emojis😡, which at least offer a way out of the Strunkian dungeon.

I should add that White’s twenty page supplement to the book, “An Approach to Style,” would require whole essay in its own right. His rules are far better than Strunk’s but are often traps for the unwary. “Do not explain too much.” (How much is too much?) “Write in a way that comes naturally.” (Only when you have learned how.) “Be clear.” (Thanks.) “Avoid foreign languages.” (Gracias.) My own counsel on style is: challenge your reader enough to keep him interested. No one wants to read what he already knows. Be playful. Spot unexpected connections. Break rules. And shun Strunk and White as the killjoys they really are.