Six months after she took her own life aged 41, Virginia Roberts Giuffre’s “memoir” Nobody’s Girl, written with her professional collaborator Amy Wallace, has been published. It is bound to evoke distinct and intensified feelings in readers because the account of her suffering, coupled with the manner of her death, increases the emotional impact of the narrative.

The writing style and tone of the book feel authentic. Giuffre, who was born in 1983, uses words like “rad,” meaning awesome or cool, and “stoner dude,” to describe someone who smokes a lot of weed plus her constant reliance “on music to make the world make sense” seem very “Xennial” as late Generation Xers or early millennials are sometimes called.

If Giuffre is to be believed, one could not fail, surely, to be moved by her account, which is quite graphic in places, and by the arc of a tragic life that is chronicled in four parts with emotive titles: “Daughter,” “Prisoner,” “Survivor” and “Warrior.” There’s no index, however, so the book could have done with a dramatis personae to help keep track of who’s who in a large cast of characters. Above all, it would have benefited from a detailed timeline of her life and the key events she describes.

Precision, particularly as to accurately identifying named abusers, when and where the alleged abuse took place and crucially how old she was at the relevant times, is not, however, the author’s strong point when it comes to standing up her narrative version of events. This precision really matters in the sexual abuse accusations Giuffre levels.

Who cares, you may ask, if she was 16, 17 or 18 when she met Jeffrey Epstein, who she accused of years of abuse? It isn’t a trivial difference, however, when it comes to statutory-rape charges. At my sister Ghislaine’s trial, as Giuffre herself notes, to her manifest disappointment: “Two of [the] accusers testified only after the judge instructed jurors that their description of alleged sexual conduct could not be used to convict [Ghislaine] of the crimes charged… “Kate” was above the age of consent in the [relevant] jurisdiction… and “Annie” [was not considered a minor in New Mexico where the alleged sexual contact had occurred].”

Giuffre had previously accused Alan Dershowitz, a sometime Epstein lawyer, of abusing her no fewer than six times – including in the Netflix series Filthy Rich – but later admitted she “may have been mistaken.” Yet in her memoir she writes: “Some critics have insinuated that there’s no way I could remember these men… But to them, I say simply this: when a man has been on top of you, his face just inches from your own, you remember him.” But if that’s true, how could she have been mistaken about Dershowitz?

When it comes to Giuffre’s firsthand account of her time “in Epstein and Maxwell’s orbit,” Amy Wallace in her preface states: “[It] was supported by thousands of pages of public court documents, including sworn depositions… [containing] the full names of many of the men who Virginia alleged she had been trafficked to. Their contents are supported by numerous other sources including… published books on the subject by authors such as the Miami Herald’s Julie K. Brown [and] Virginia’s former attorney Bradley Edwards…” As if the sheer quantity of such material and the implied quality of the names in support are standalone proof of Giuffre’s overall veracity. This is a surprisingly Stalinist approach to corroboration.

Giuffre herself states in the introduction to her memoir, “Until now I have never told my whole story. Doing so allows me to fill in gaps, to provide context where it has been sorely lacking, and in key places to set the record straight.” She confirms, however, that she did in fact “complete a 139-page typewritten manuscript entitled The Billionaire’s Playboy Club.” Although unpublished it found its way into the court record.

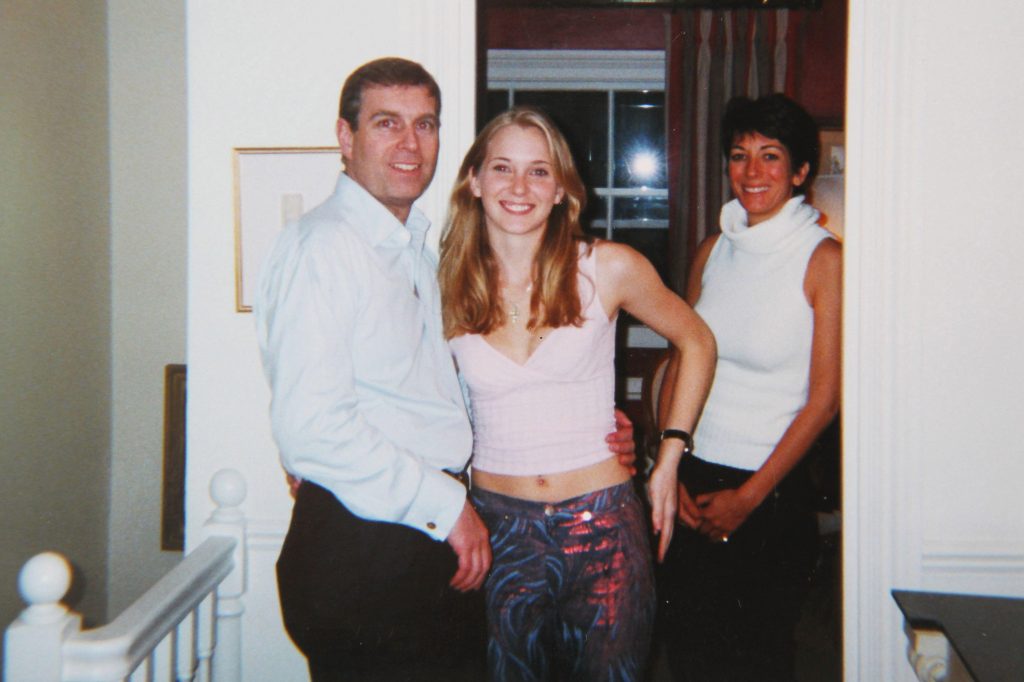

The “context” she then provides about that version of her life is to blame the Mail on Sunday reporter Sharon Churcher for advising her (in 2011/12) to fictionalize parts of the narrative to avoid being sued. This, she says, accounts for why “my third encounter with Prince Andrew… occurred at Zorro Ranch [in New Mexico], not where it actually occurred: the Caribbean.” It wasn’t until 2019 that Giuffre’s own lawyers had to admit in a court document that the manuscript was indeed “fictionalized.”

It is from this disclaimed memoir that Julie K. Brown directly quotes Giuffre verbatim or paraphrases her in her 2021 book, Perversion of Justice. The book is dedicated to Giuffre, which might explain why Brown was happy to corroborate her version of events to Wallace. Is it any wonder, therefore, that Giuffre’s credibility issues were one reason she was neither named as a victim nor called as a witness in my sister’s prosecution? She claimed she was not called as a witness because she would have been “a distraction” but that’s a self-serving lie.

At Ghislaine’s sentencing hearing, despite not featuring in her trial in any capacity, Giuffre – who was never cross-examined under oath in any legal proceeding – was allowed by the judge to provide a victim-impact statement. The statement itself could not be subjected to cross-examination and Giuffre’s most serious and untested allegations added time to Ghislaine’s sentence.

Giuffre frequently writes lines such as, “I didn’t want money. I wanted justice,” and mentions her charity, SOAR. Yet despite having reportedly received more than $20 million in settlements – including at least $2 million from Prince Andrew – the charity was never fully established, lost its tax-exempt status due to inactivity and has no record of charitable giving.

Nearly three-quarters of the way through the book, readers are asked if they “can remember America before the #MeToo movement” which reached its apex in late 2017. In the pursuit of “justice,” #MeToo was a wave that Giuffre, guided by her ruthlessly adept advisors, skillfully – and above all, profitably – rode to their mutual benefit.

While that movement has clearly raised increased public awareness of sexual misconduct, it has also generated an important debate over the erosion of core principles of natural justice. The bully pulpit of social media too often bypasses traditional mechanisms of due process, with allegations leading to devastating reputational consequences before a formal investigation or hearing can occur.

By May 2020, presidential candidate (as he then was) Joe Biden, facing allegations from a former staffer of sexual harassment 27 years earlier, produced a more nuanced interpretation of the original #MeToo slogan, “Believe women,” when he said: “[There is a] belief that women should be heard… that [they] deserve to be treated with dignity and respect… and that their stories should be subject to appropriate inquiry and scrutiny” (the italics are mine).

Even if only parts of Giuffre’s account are true, she is still a person who suffered and deserves sympathy. But that cannot excuse the fact that she accused innocent people of serious crimes and destroyed reputations and lives.

Her claims – like anyone’s – must be carefully vetted. To approach this book with the assumption that she is telling the truth necessarily means imposing a presumption of guilt on everyone she has accused of sexual assault, placing the burden on them to prove their innocence. This is contrary to all principles of natural justice.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 10, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply