Only two of the Beatles’ pop contemporaries are depicted on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. One is Bob Dylan. The other is Dion DiMucci. In a pleasing third-act twist, Dylan contributes the liner notes to Dion’s new album Blues With Friends — an act of deference that the recipient is still processing. ‘I asked him, I didn’t know if he had the time, but he sent me back those paragraphs and said that I knew how to write a song.’ He whistles. ‘That’s from a Nobel Prize winner. I thought, I’ll take it, I’ll take it!’

So he should. Dion — like Kylie, a single moniker suffices — is one of the last living links to the early days of street-corner rock ’n’ roll. A rough-around-the-edges Italian-American from the Bronx, he headed the first wave of smart-assed tough–talking urban singers. As the front man of vocal quartet Dion and the Belmonts, he enjoyed huge success in the late 1950s with doo-wop perennials ‘Teenager in Love’ and ‘Where or When’. After going solo, he recorded ‘The Wanderer’, ‘Runaround Sue’ and ‘Ruby Baby’. Later, he made the shift to socially conscious singer-songwriter (Dion recorded the original version of ‘Abraham, Martin and John’ in 1968, quickly picked up by Marvin Gaye), negotiated heroin addiction and converted to evangelical Christianity.

Bruce Springsteen, one of numerous A-list guests on Blues With Friends, describes Dion as the link between Frank Sinatra and rock ’n’ roll. Lou Reed inducted him into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1989. Simon & Garfunkel performed ‘Teenager in Love’ at their farewell concert in 1970. He’s well connected. A made guy.

It turns out Dylan and Dion go way back to 1962, but then Dion goes way back with pretty much everyone. Rock ’n’ roll history spirals inside him like the rings in an old oak. The recent death of Little Richard prompts a memory of touring with the great bawler, where he observed the contrast between Richard’s bug-eyed preacher persona and the private man. ‘When I was alone with him, he was very thoughtful, very considerate and just very present. He was not a self-centered crazy guy, the way he would appear on stage or on talk shows. He had another side to him.’

He toured with Sam Cooke, who ‘sheltered me and championed my cause. He took me to see James Brown in the black nightclubs, and looked out for me. He was a very refined guy’. In February 1959, Dion was offered a seat on the tiny single-engine plane that crashed and killed Buddy Holly, the Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens. Traveling together on the Winter Dance Party tour, following a concert in Clear Lake, Iowa, the four men discussed flying to their next booking. Dion felt the $36 ticket price was a stretch and opted instead to slog it out on the tour bus. ‘I was the only guy in the room who was alive the next day,’ he says.

Before Holly died, he told Dion: ‘I don’t know how to succeed, but I know how to fail: try to please everybody, that’ll make you fail.’ He took the advice to heart. He’s especially proud that Blues With Friends features 14 original new songs. ‘I don’t care about nostalgia,’ he says, and I believe him. ‘I don’t care if you remember the old days.’

At 80, he still has plenty of accentuated Noo Yoik moxie to burn. Calling from his lakeside home, where he is self-isolating with his wife, Susan (they met when he was 17 and she was 15, and have been married for 57 years), he describes himself as a ‘rhythm singer’. He’s a rhythm talker, too. Hard facts are ‘bona fide certified’. He works like ‘a donkey with diamonds on my back’. On a hot writing streak, he ‘steps under the spout where the glory comes out’. His aphorisms aren’t just quirky; they feel useful: ‘A good song never gets tired; only the singer does.’

On Blues With Friends Dion has pulled rank, calling in favors from many of the second-generation rock-and-rollers he influenced over the years. Hence the contributions from Dylan, Springsteen, Paul Simon, Van Morrison — ‘I go back with Van to “Brown Eyed Girl’’’ — as well as younger acolytes such as Joe Bonamassa and Samantha Fish. He haggled with Morrison. Dion wanted him to play saxophone; the Irishman insisted on singing — ‘and lemme tell you, you haven’t lived until you sing with Van Morrison’.

He regards his elder statesman status philosophically. He’s clearly proud of it, but seems uncomfortable being reminded of the fact. ‘Paul Simon lived in Queens, and he grew up with my music. They’ve all told me how they listened, but sometimes it’s hard to receive it. They say the last stage of humility is learning how to receive. I don’t think I’ve gotten there. I still push back. But these guys have kept me young over the decades, and inspired me back.’

The swaggering protagonist of Dion’s signature song ‘The Wanderer’ is an archetype, he says, drawn from the tattooed vest–wearing hard cases who prowled his old Bronx neighborhood — with, I suspect, an element of self-portrait thrown in. ‘I was born knowing everything,’ he laughs. ‘Meanwhile, you don’t know anything. It’s that bullshit thing. “The Wanderer” is a funny song: “I roam from town to town, I go through life without a care / I’m as happy as a clown, with my two fists of iron, but I’m going nowhere.” The guy’s in on it. I thought he was worth a song. It seems like every decade or so, that same theme reappears. On this album it’s “I Got the Cure”. Same guy.’

***

Get three months of The Spectator for just $9.99 — plus a Spectator Parker pen

***

On ‘I Got the Cure’, a brash, braggadocio blues, Dion sings ‘Don’t need no smack, or crack cocaine’. He cleaned up from heroin in 1968, thereafter devoting himself to the Lord rather than the needle. ‘It does seem like a different lifetime, but it’s something you never forget,’ he says. ‘There was a time when I thought that wealth, pleasure, power, honor would fill me up. I thought that was what I needed. Then I found out different. Fifty-two years ago I got on my knees and said, “Man, I need some help.” ’ The catalyst was the death from an overdose of his friend and fellow doo-wop singer Frankie Lymon. ‘I was devastated. I said, “God, help me.” I didn’t know God from a hole in the wall — but I asked, and I spun around. I haven’t had a drug or a drink since.’

Perhaps he knew God better than he realized. Rock ’n’ roll mythology is, after all, simply a variation of religious fervor. ‘I was always a weird kid anyway,’ he says. ‘I always liked to read Thomas Aquinas, St Augustine, St Francis, Thomas Merton. They were so radical! I heard that St Francis gave up all his money and walked around with no shoes — what the hell was all that about? I wanted to know.’ The blues, for Dion, is a form of sacred communion. ‘I define it as the naked cry of the human heart, longing to be in union with God. Like the Psalms. King David wrote these songs — if you retitle them, you could call them the blues.’

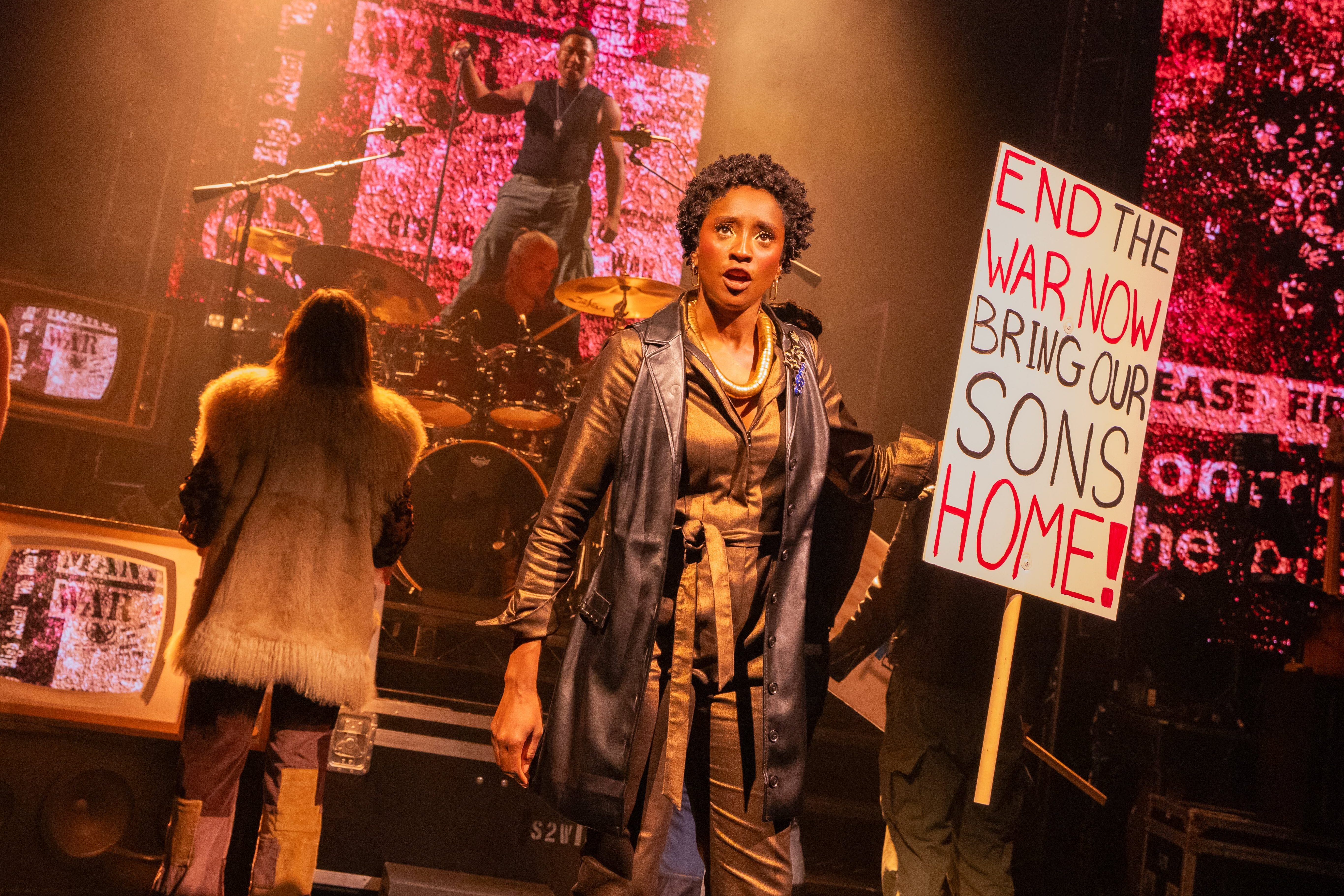

A jukebox musical based on his life and music was due to open Stateside this month, but has been delayed by COVID-19. The Wanderer, with a book by Charles Messina, will premiere next April. Dion watched it develop, saw his four-score years unspooling before his eyes. ‘This kid wrote some story,’ he says. How could he not? It’s been some life.

Blues With Friends is out on June 5 on KTBA Records. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the US edition here.