They passed into the harbor of Favignana at the beginning of spring, the island’s single small mountain heaving into view from the Trapani ferry, burned brown by centuries of parch and abandonment. A disused Bourbon castle sprawled upon its summit, while below it near the water stood an old tuna-processing factory with nineteenth-century industrial chimneys. The raffish little port lay alongside. They came down on to a deserted quay with the harbor on their right filled with the pale blue and copper boats of the bluefin fishermen listing in shallows. The fishermen seemed to have walked off into a different life, perhaps never to return.

In the main square there were shops selling cans of local tuna with the Rais, the sea shaman who led the harvest of the bluefin tuna every year, pictured on the lids. A man with a curling white beard, à la Neptune. Even the servizi turistici was open, its walls advertising nautical adventures. When they ventured inside, an old lady, who had just opened up shop without expecting a soul to appear, looked up from her newspaper and coffee and said, with resort-town English: “Are you serious?”

The freezer was filled with steaks, though the agent had said nothing about permission to eat them

“You’re open,” Ben said, and put down the bag he was shouldering. “We can’t be the only ones.”

The woman gave him a smile edged with a little grimness. “You are the only ones.”

They all shook hands.

“Well, we are the only ones then. We are looking for a house. For a month.”

“Not a problem,” said the relieved agent.

Behind them on the wall, the island map was pinned. Shaped like a butterfly, the island was mountainous in the west, flat and gently rolling in the east. Between the two “wings” was a small isthmus where the town lay with its port. In the east, most of the holiday homes that were rented out for summers.

A wealthy architect in Rome owned a villa at a place called Cala Rossa. The woman put her finger on the place. It was a cove, a cala, with only a dirt road approaching it. It was only two or three miles to the port, but a mile on Favignana felt like ten elsewhere. The rent was reduced because of the season: $500 for a large house with its own herb garden. The architect had made it modern inside. There was no internet now, but the fridges were American. “We’ll take it,” Raphie said immediately, and within a quarter of an hour the agent was driving them to Cala Rossa herself.

In a Fiat Uno they barreled between low walls infested with paddle cactus, the fields broken up by flat-roofed houses and by tormented pines, bursts of African primroses. Here and there among the cheaper cinder-block houses stood sleek whitewashed villas surrounded by walls with satellite dishes mounted on their roofs. They contrasted strangely with the empty quarries still open to the sky and filled with ladders left behind by the dead. The land littered with white stones. Bleached and shadeless, with the dark tourmaline sea behind it, like Ireland or the Hebrides, except for the gardens planted in tufa pits to spare them the wind. Gardens called hypogea.

A half mile beyond the Cala the rental villa stood on the edge of a field of grassland that shelved gradually towards the sea. It was called “Aegusa.” The shutters Sicilian blue, the lintel above the main gates bearing a limestone dolphin with a human face. The windows were Arabic in style, covered with pale-green metal grilles. The whole whitewashed complex shone as if reflecting the sky’s subtle luminosity.

Raphie got out first and went to the edge of the wild scrub, where there was no wall. She felt elated after days on the road driving from Milan. When Ben came up behind her to fold an arm around her shoulders, she said: “See, we’re saved. Look at it.”

“A place near the far side of the world,” he thought, a little more pessimistically but enjoying the pun.

The main room was crossed by high beams and the tall windows were brand new, double glazed. The furniture, the agent said, was from Milan. Moroso. Did they know it? Molto chic. But there were also gloomy Sicilian antiques. “Dottore De Angelis won’t be back for the rest of the year. I told him you were a film director and your girlfriend is a writer. He was very pleased to have artists in his house. Between you and me, I think he is hoping you settle in for a while.”

They chatted for a while. Once the island too had been called Aegusa, like the house. Island of goats. But where then were the goats? The agent made it sound like a dark secret.

After she had left they showered, made love on the sofa and then picked some grasses from the garden to put into vases. The house already had their scent. Beyond the cathedral windows the steady line of the sea calmed them.

“You know it’s the architect’s love nest,” Raphie said. “No one has ever lived here. You can tell.”

“Now us.”

“We can make it ours, don’t you think?”

They rifled through the kitchen and found that it was over-abundantly stocked. The freezer of the huge American fridge was filled with steaks, though the agent had said nothing about permission to eat them. They decided that it was understood they could. There was even vacuum-packed Bavarian bread. They opened some cans of soup and had lunch at the kitchen bar with its forlorn Moroso stools. Now, as if for the first time, they heard the wind battering the casements.

“I tried to call home,” Ben said, “while you were in the shower. But no luck. I was relieved. It’s a relief not to have to talk to them.”

“I know. I got through to my dad while you were in the shower and then I hung up.”

“Good. We’re free. Shall we walk up to the Cala and have a look?”

By the time they reached the tufa cliffs, storm clouds had appeared over Levanto, the small island opposite them. The shallows around the old quarries were dark red with algae, giving the appearance of spilled blood. A path wound its way over them past a multitude of dark man-made buttresses.

Here they found chiseled geometric doorways and caves leading into unlit passageways which had once served as mineshafts. The entrances were covered with decades of carved graffiti. After a while they chanced upon a huge block with an accidental seat carved into its surface. They climbed up on to it and unpacked the slowly defrosting cakes which they had brought with them.

Out of the wind, it was warm enough to take off their jackets and they lay back, sheltered by the stone. Ben soon sat back up, however, and scanned the cubist cliffs opposite them. It was easy to imagine it during a normal high summer, infested with semi-nude sunbathers and people swimming in from yachts moored in the shallow bay. Typical Sicily.

Yet just as he was thinking this he felt that someone unseen was watching them — among so many hundreds of perches and ledges it would hardly be difficult. It was a voyeur’s paradise.

He felt that someone unseen was watching them — among so many hundreds of perches and ledges

Looking up at the same cliffs a second time he now caught sight of someone lying in the same way as themselves, a girl laid out on a small blanket and listening to earphones. So their remote environment was not entirely free of other people. He lay back and watched the woman for a minute or two, curious then slightly aroused while he let Raphie snore contentedly. Then in just a few moments — as he looked up again — the apparition on the blanket disappeared. Had he imagined it? Either way he decided to say nothing about it.

That night they made a fire outside in the pit in which they barbecued pork chops from the freezer. They cracked open cans of German beer and toasted their bare feet at the fire; the French windows of the house were opened and a rich torrent of musical sound poured into the garden: the Dave Brubeck Quartet, “In Your Own Sweet Way.” Even twenty-four hours earlier, as they had raced south in their rental car — which they had abandoned in Trapani on the mainland — they had never imagined that they would land in such a sweet spot. “I thought this afternoon,” he said now, “that it was too perfect that we ended up here. It’s as if someone we don’t know planned it. As if they were waiting for us.”

“The Fates.”

“Something like that.”

She said: “It’s strange how you can hear the gulls even from here. They must be a quarter mile away.”

Some could even be seen, wheeling above the bluffs.

“I feel,” Ben said, “that I could get some work done here. Maybe. It isn’t what I was expecting. It’s more gentle.”

“Is it?” she thought.

To her it was just the opposite. The wind had a venom to it; it was why the islanders built their gardens underground.

During the night she listened to it while Ben slept. Sheared off leaves ricocheted off the glass panes and there was a sizzle of hurled dust. Quite suddenly, in the space of a single day, her mind had become attuned to something different and new which was symbolized to her by that distinct wind, which must have been an Egadi wind, a wind particular to that place. The favonio. But it was surely not possible that it was speaking to her. It merely kept her awake, playfully, and toyed with her sweet exhaustion. Later, Ben woke as well and they made love again, with unusual ferocity. It was not at all like their previous amorous siestas, which had always been tinged with self-consciousness and even a little irony. Now all that was gone. She hardly recognized him.

Afterwards they lay in their sweat, numbed into semi-consciousness, while the shutters downstairs rattled and slammed where they had forgotten to hook them in place. Her previous life, all words and social whirl, had become miniaturized in her own perspective until it seemed like a theater play of little human dolls.

Then a violent thought rose into her consciousness. I must be pregnant. It simply has to be. Yet since there would be no way of verifying it, the thought would lie in beauty inside her for a long while, day after day, and she wouldn’t say a word about it to him. But someone had once said to her that one always knows. The spark inside you lets you know.

*****

She got up long before him and went downstairs to make toast and jam. Overnight the weather had completely changed. Now it was clear and mild, warm even. It was as if another season had stepped over the Mediterranean from Africa and imposed itself. The mountain on the far side of the island appeared hazily remote and insubstantial, suggesting an optical effect created by an atmospheric quirk. The island was like some animal lying on its side half-asleep, yet aware of the small parasites crawling over it. Gusts of hot wind burned her face.

She went out with her toast and coffee and wandered down to the bluffs. The thyme quivered there happily and at the bottom of the cliff almost at once she noticed a small jetty obviously attached to the house. Roped to this, in turn, was a small skiff with an outboard motor. A visitor.

Her heart missing a beat — a second-long panic — she scanned the cliff until she spotted the visitor. It was a girl about her own age but blonde, dressed in nothing more than a bikini and carrying in one hand a pair of scissors with which she was snipping tufts of wild herbs from the cliff and stuffing them into a plastic bag tied to her waist by a length of string.

A German hippy, maybe, but at any rate an intruder into private property. Annoyed, Raphie called down to her in English and the girl looked up with pure blue eyes. There was nothing in them but antic hay and sardonic good humor.

“Are you the renter?” she called back up in English, making it clear she wasn’t German after all.

“Who are you?”

“I’m Erica, the architect’s daughter. I didn’t know you’d be here yet.”

“Well of course we’re here.”

The girl clambered up to Raphie, all springtime sweat, tanned flesh and feral agility. Finally they shook hands and the sweat came off on Raphie’s palm. A touch of oil. The eyes were so bright they were a little crazy.

“That’s our family boat,” she said, pointing to the skiff. “We keep it in Marsala. Faster than the ferries.”

“Did you come over to get herbs?”

“Actually I was thinking of making myself dinner and staying over a night. Papa said it would be fine with you guys.”

“He did, did he?”

“We keep an open house. Open table and all that. Why don’t I make you dinner with these?”

And she held up the bag of herbs.

“I should ask my husband though —”

“Oh, he won’t mind. Let’s go see him.”

‘If you were the designated demon you would go as far into the labyrinth as your nerve would take you’

No one had mentioned a daughter, an open house or a private boat belonging to the property but Raphie felt herself giving way under the impact of a strangely pleasurable momentum. Erica gave her the herbs and they walked gaily back to the house, the visitor telling her that she had been scuba diving in the submerged tufa quarry caves. Outstanding. They found Ben making himself coffee in the kitchen and his three seconds of complete surprise didn’t last as long as Raphie thought they ought to.

“Dinner with a visiting cook?” was all he said in the end. “All right. Erica, are you sure you’re not a mermaid?” “Not at all.”

“She says she wants to stay the night. Are we OK with that?”

“Well, we can’t send her back into the open sea at night. Even if she is a mermaid.”

“She’s not a bloody mermaid,” Raphie said.

“Which room do you usually take?”

Erica replied that the room next to the kitchen on the ground floor was usually hers when the family was at Aegusa. She was fine with it.

This arranged, they took a pitcher of lemonade mixed with gin and went down to the pool where pieces of “Greek” statuary evidently looted from roadside stalls stood among the lemon trees. The British couple stripped down to swimmers and plunged into the water, instantly galvanized and stimulated by the small doses of gin. The visitor was now welcome, amusing, because of course she was a diversion. So they chatted for an hour and swam together and finished the pitcher of gin. Raphie went up to the house to make another. Since they were alone together for five minutes in the pool Erica said to Ben: “I’ve seen you before somewhere. Do you ever go to Vienna? Milan?”

“We were just in San Remo,” he began.

And he explained his debacle.

“Allora I wasn’t there,” she said. “I’m sure you’re exaggerating about the debacle.”

He didn’t want to say it but there was something contrived a little under the surface of her borrowed English. There flowed a deeper current of something alien moving contrary-wise against the surface. A few vowels pronounced in such a way that wider horizons were suggested. But Raphie then returned before he could say anything and as the pitcher of spiked lemonade was set down by the pool Erica suggested that, since they had the whole day before them, why didn’t they take a little trip in her boat?

“Where?” Raphie said.

“There’s an abandoned quarry called the Labyrinth of Caves up the coast a bit. Want to go see it?”

“Well sure,” Ben said. “I’m always up for a labyrinth.”

*****

High noon. The waters had become still; golden sponges glowed through the aquamarine from the seabed. They passed along the coast in the skiff towards a place called Punta San Vituzzo, the bleak stone formations baking in morning light, fragments of wall glistening with prickly pears. Before long they were abreast of the Labyrinth of Caves. It looked like a Stone Age city abandoned before the invention of writing. All along it the rock had been broken by both machines and by the elements, and above this shattered waterline rose geometric doorways leading into the caves. There they tossed anchor and dived into the water, then swam to the submerged platforms underneath the Labyrinth. As they lounged there in the sun Erica said: “We used to play here as children. It kind of has bad memories for me.”

“Play what?” Ben said.

“Hide and seek. Things like that.”

She had other children to play with in those days? She was an only child or she had siblings?

“Children from the villages. We used to dare each other how far into the caves we could go. Then the search party would go look for them. If I’d had siblings we would have done more dangerous things.”

They drank freely, a little too freely, and ate in the same way. A hazed moon rose over the sea

“What did your parents say?”

“Obviously we never told them. It was a secret game. The adults were superstitious about the caves.”

“About what?” Raphie asked.

Erica combed her hair with her fingers and talked with her eyes shut, her face tilted up to receive the sun. It was like someone drinking after a long thirst. Children, she said, are not as afraid of the past as adults. For the children at that time the Labyrinth of Caves induced fear for different reasons. There was no end to those underground passageways, no knowledge of where they led.

For the adults it was different. The caves were a place where the Phoenicians had buried their dead. The islanders did not cease to mention these facts, which they treated as some kind of tremendous archaic gossip. Over millennia the rocks had become encrusted with bones and pottery and secrets. Libyan prisoners of war had been deported there during World War One and many were still there entombed in the quarries where they had died of malnutrition and malaria.

“But tell me about the game,” Raphie said.

The children drew straws to see who would be “it” and then the designated person would have an hour to lose herself inside the labyrinth.

“But being selected as the ‘it’ was always the last thing you wanted to be. You would be called the demon and the game was ‘catch the demon.’”

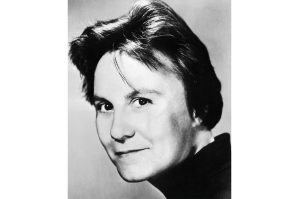

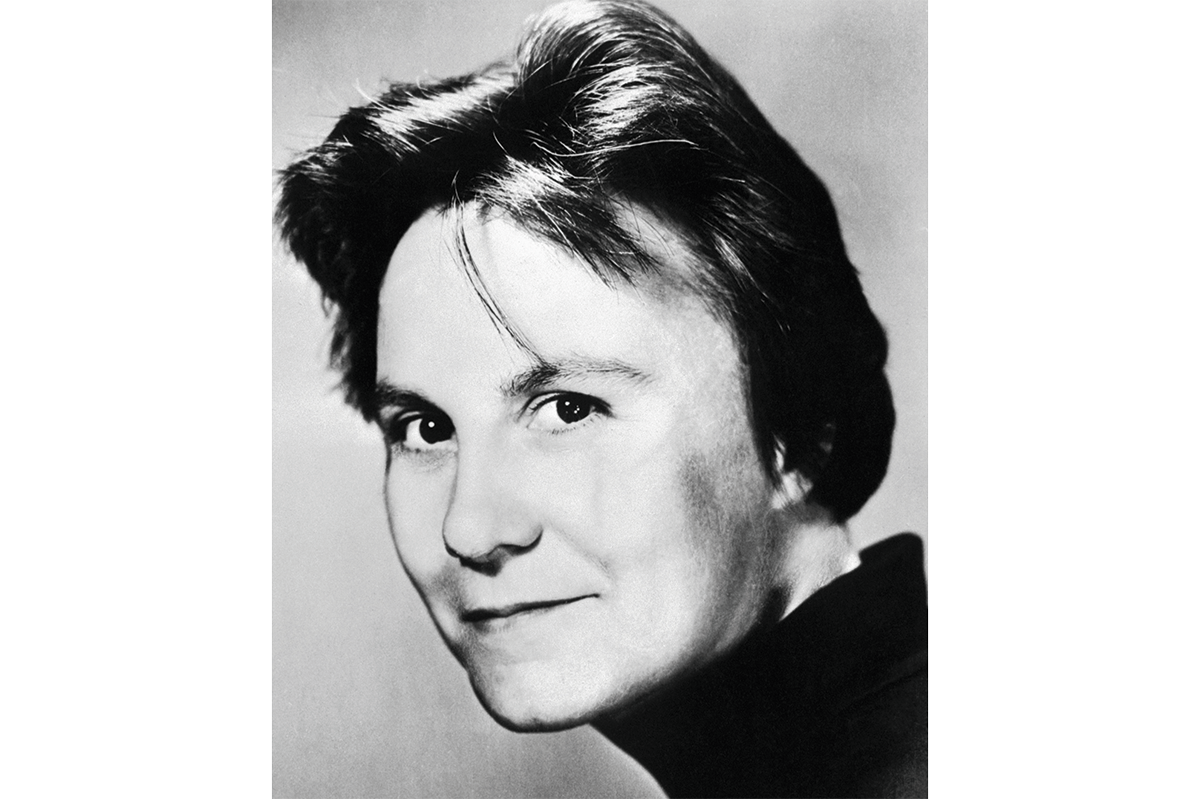

(Alex Green)

(Alex Green)

“Children are sick,” Raphie sighed.

“If you were the designated demon you would go as far into the labyrinth as your nerve would take you. If they couldn’t find you, you could come out alone and claim victory. Then the others had to buy you ice cream.”

The word for demon in Sicilian dialect was dimoniu.

After a while they swam back to the boat. Erica had brought along a small plastic kitchen box with a kind of jam in it, a dark paste made, she said, from the jujubes that grew in her father’s garden. To be eaten on crackers, which she had also brought with her. It was figs, jujube, sugar and tramodolo. The last a substance the British couple had never heard of.

Jujube, Erica said, was a stimulant beloved of the Romans. It came from the lotus tree. “Go on, give it a whirl. If you throw up no one’s here. You’ll literally be lotus eaters.” And the paste was surprisingly tasty. It was thought by the ancients to make people fall in love.

After that, they lay naked and wet in the boat and Raphie, for one, thought that she could hear the wings of dragonflies flying over the water’s surface, but slowed down so that each beat was audible.

By the time they had returned to the house the sea had gone slightly darker. Swallows flitted over it. They went up to the pool and Ben and Raphie had a cool-down swim while Erica continued on to the kitchen to make dinner with the herbs that she had collected earlier.

“I feel a little stoned,” Raphie said as she held Ben’s hand by the pool. “Or just happy. I can’t tell which.”

“Same.”

She pointed at the architect’s garden. “Those are the lotus trees then. Is that why?”

Ben shrugged. “Who cares? It’s the mood that matters.”

“It must be so weird for her coming back to her own house and finding two strangers in it. Don’t you think?”

“That’s why she’s going out of her way to be nice.”

“Did you believe all that stuff about the dimoniu?”

“Sure. Demonia. The designated demon. Love it. It’s a creepy place. Kids always seek out creepy places.”

“That’s what I thought.”

Erica returned with a casserole filled with the chicken she had made and they ate it with a bottle of Marsala which the daughter of the house had plucked from her father’s cellar located in the tunnel system under the house. Ben read out the label: De Bartoli. Vecchio Samperi. Erica explained that it was not fortified like the Marsala preferred by the British. It was pre-British, a style called perpetuo.

“Perfect,” Raphie said. “Since we’re post-British and all.”

The chicken was intensely herbal and rich with lemons also from the garden. They drank freely, a little too freely, and ate in the same way. A hazed moon rose over the sea. Below the wall, clumps of Tree Spurge had taken on a pale golden tint and the mastic trees around them were now underlaid by a dark moist gloom as the heat receded. Slopes of sumac and thyme still seething with crickets and purple-tinged night moths, puckish visitors from the underworld. Enchantment had fallen upon them and Ben and Raphie began to lose the threads of their thoughts. Words came out of their mouths that made no sense but which made them giggle and utter still more nonsense.

Abandoning etiquette, they began to eat with their hands. Their laughter became loud and unhinged, and as Ben looked into Raphie’s face he found it hard to recognize her. Something crazed and archaic had come into it. A thread of saliva fell in slow motion from her lower lip and attached itself to her plate.

“I need to take a piss,” he said then, and got up unsteadily. The two women looked at him with an acid merriment.

“Don’t be long,” Raphie said.

He staggered through the garden, reeling from side to side, and crashed through the kitchen door into the house. On the table there he saw Erica’s travel bag and next to it a box of medication called Kolibri with tramadolo chloridatro clearly marked on the side. A vague feeling of unease swept through him but he was unable to hold on to it. In the bathroom he had to hold both walls to stay upright. “I’ll lie down in bed,” he thought. “Just for a moment.” And this he did, collapsing into the matrimonial four poster and quickly falling asleep. The last thing he saw was the tile triskele above the door to the bathroom and the white slope of the mosquito net. When he woke he realized at once that hours had gone by. He went groggily into the bathroom and turned on the light. In the mirror he saw that his face was covered with lipstick kisses and there was a small bruise on his neck. “Raphie,” he thought. She must have come to find him and yet she hadn’t stayed. Only a lover’s bruise.

In any case she was not in the house. He went back down to the pool and found her there fast asleep on the wall with a garden cushion laid under her head. The remains of the dinner had been cleared away and, now that he collected his thoughts, he recalled that Erica’s things were no longer on the kitchen table. Then what about the lipstick on his face? His whole body felt out of joint, the skin rubbed almost raw and now tender. He couldn’t wake Raphie without wiping off the lipstick first; this he did in the pool. Of course: she never wore lipstick.

Sitting on the wall next to her, he took her feet in his hands and warmed them. It then occurred to him that he should go and check on Erica in her room, since there was already a streak of dawn light in the sky. Yet he didn’t want to abandon Raphie either. Torn, he finally decided to creep back to the house and see if Erica was asleep in her bed. The idea was quietly exciting, since he had now come to the conclusion that those lipstick kisses could only have come from her, though how and why he could not say. Accordingly he went to her room, only to find it empty. She had clearly not slept in it and, as he had noted before, the kitchen was equally cleaned up. In a state of bafflement, he returned to his own room and, impelled by instinct, he took a quick look at his valise and found that his wallet had been emptied of all its cash and cards.

‘No,’ she said in a hushed voice. ‘Don’t touch me.’ Some sly spirit had quietly come between them

“Well, well,” he said aloud, but found himself smiling as if he didn’t care as much as he should have. Erica must have felt entitled to take everything after spending hours in his bed. Yet during the day, after Raphie had finally woken, he didn’t mention either of these events to her — though suggesting that it was perhaps time to move back to the main island where he could get some extra money from his bank in London.

“Why?” she said as they drank coffee by the pool again, and after she had noted — as if in passing — that the boat was missing from the jetty.

“I just may have miscalculated the money thing,” he said as airily as he could manage.

“She’s gone off,” Raphie then said, lowering her gaze until the sea’s glitter filled it. “Just like that without a word.”

“Rich kids.”

“They’re not terribly polite are they?”

“Not at all.”

“Still, she could have said goodbye. What an oddity.”

*****

A week later at the Villa Igiea at Rocco Forte in Palermo, Ben left Raphie in a hot bubble bath in their room and went down to the pool overlooking the sea in a bathrobe. As he sat there drinking a negroni, a waiter came to him and said that there was a call for him from Signore Di Angelo, the owner of the house on Favignana. The hotel would like to put the call through on Ben’s mobile. He agreed. The architect at last, the man with the strange daughter. The voice garrulous but cosmopolitan.

“We were worried about you,” the architect in far-off Milan said. “I called the agent and she said that you weren’t answering your messages. Anyway, I hope everything was all right. You cut your stay short. I can’t refund, I’m afraid.”

“It’s quite all right.”

“May I ask, did you have any visitors while you were there?”

“No. I was wondering actually if maybe your daughter…”

“We don’t have children, thank goodness. But I was thinking about someone else.”

“Oh?”

“We had a maid whom we fired six months ago. She was stealing my wife’s earrings. Bloody Serbians. She used to stay with us at the house in the summer.”

“Is that so?”

“She probably stole some of my wine last time. Never mind. The alternative world of Serbian maids.”

There was a cracked laugh.

“Quite,” Ben said. Later he sat on the bed next to Raphie, her eyes not glancing to acknowledge his presence, and he quietly laid a hand on her stomach under the bathrobe. It was hot and moist and, she murmured, whatever was inside her had felt like a volcano coming to life all day long. An animal life asserting itself. The test they had done at the fertility clinic in Palermo had confirmed her pregnancy. “Must have been the island winds,” she had thought to herself at that moment of discovery.

Looking at her face, he noticed that it was covered with drops of sweat, as if a fever had swept down upon her. She hadn’t complained about it. He took her hand and it was hot as well. He reached out to touch her brow and she recoiled slightly, still not looking at him. “No,” she said in a hushed voice. “Don’t touch me. It’s all right.” Some sly spirit had quietly come between them.

At dinner that night they hardly spoke as they ate their lobster bisque and squid ink pasta and he tried to distract himself with a whole bottle of Greco di tufo. He talked about his idea for a new script, the film he was going to make next. She said nothing, but he felt that she was listening in her way. Careers and plans seemed to matter a lot less than they had a month before.

“I think it’s going to be a girl,” she said at length. “Should we call her Erica?”

“I don’t know. Should we?”

She reached out for a moment and grasped his hand.

“She’s moving already.”

“Look, I think you should sleep properly tonight and we’ll talk about it tomorrow. Fair deal?”

A quick fury came into her eyes but then subsided as she realized that it was hopeless with him. He had gone cold.

Ben slept more deeply than he had expected to as he lay next to her and his dream was beautifully preposterous. There he found himself in a forest of the north, the forests he knew from his childhood, descending in bare feet along massive steps cut into a hillside that plunged down to a river of broad and powerful sweep. Along the far bank, a row of massive logs made from fir trunks bumped their way through rapids demonstrating the nearby hand of humans, and yet he could sense that it was thousands of years in the future. Midstream, a stag struggled to make its way across the same rapids, its legs splayed as it lost its footing. It was midsummer, in the eternal peace of nature. On the far side and half lost in the shade of the great elms, he saw Erica smiling at him, lying naked on the grass among dandelions but seeming to know what he was thinking and feeling. “You’re late,” she said in a voice that simply appeared in his mind, and then he began to wave as if from a moving train window. “You’re carrying my child,” he said back to her, and he could tell from her expression that she didn’t deny it.