They didn’t call Diogenes “the Cynic” for nothing. He lived to shock the (ancient Greek) world. When I’m dead, he said, just toss my body over the city walls to feed the dogs. The bit of me that I call “I” won’t be around to care.

The revulsion we feel at this idea tells us something important: that the dead can be wronged. Diogenes may not have cared what happened to his corpse, but we do; and doing right by the dead is a job of work. Some corpses are reduced to ash, some are buried, and some are fed to vultures. In each case, the survivors all feel, rightly, that they have treated their loved ones’ remains with respect.

A teenager describes how, ten years after losing his father, he discovered they could still play together

What should we do with our digital remains? This sounds like one of those noodly problems that keep digital ethicists like Carl Öhman in grant money. But some of the stories in The Afterlife of Data are sure to make the most skeptical reader stop and think. There’s something compelling, and undeniably moving, in one teenager’s account of how, ten years after losing his father, he found they could still play together; at least, he could compete against his dad’s last outing on an old XBox racing game.

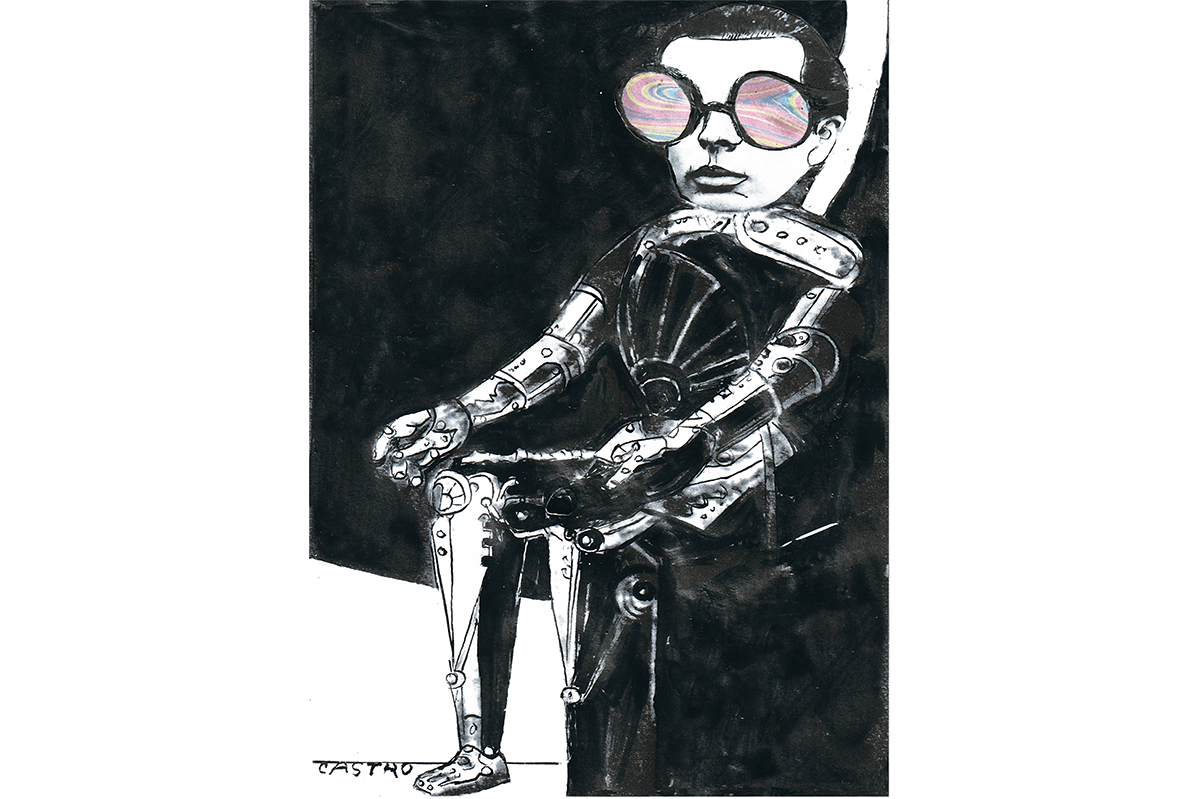

Öhman is not spinning ghost stories here. He’s not interested in digital afterlives. He’s interested in remains, and in emerging technologies that, from the digital data we inadvertently leave behind, fashion our artificially intelligent simulacra. (You may think this is science fiction, but Microsoft doesn’t, and has already taken out several patents.)

This rapidly approaching future, Öhman argues, seems uncanny only because death itself is uncanny. Why should a chatty AI simulacrum prove any more transgressive than, say, a photograph of your lost love, given pride of place on the mantelpiece? We got used to the one; in time we may well get used to the other.

What should exercise us is who owns the data. As Öhman argues:

If we leave the management of our collective digital past solely in the hands of industry, the question “What should we do with the data of the dead?” becomes solely a matter of ‘What parts of the past can we make money on?

The trouble with a career in digital ethics is that, however imaginative and insightful you get, you inevitably end up playing second fiddle to some early episode of Charlie Brooker’s TV series Black Mirror. The one entitled “Be Right Back,” in which a dead lover returns in robot form to market upgrades of itself to the grieving widow, stands waiting at the end of almost every road traveled in this book. Öhman reminds us that the digital is a human realm, and one over which we can and must exert our values. Unless we actively delete them (in a sort of digital cremation, I suppose), our digital dead are not going away, and we are going to have to accommodate them somehow.

A more modish, less humane writer would make the most of the fact that recording has become the norm, so that, as Öhman puts it, “society now takes place in a domain previously reserved for the dead, namely the archive.” (And, to be fair, Öhman does have a lot of fun with the idea that by 2070, Facebook’s dead will outnumber its living.) Ultimately, though, Öhman draws readers through the digital uncanny to a place of responsibility. Digital remains are not just representations of the dead, he says. “They are the dead, an informational corpse constitutive of a personal identity.”

Öhman’s lucid, closely argued foray into the world of posthumous data is underpinned by this sensible definition of what constitute a person:

A person is the narrative object that we refer to when speaking of someone (including ourselves) in the third person. Persons extend beyond the selves that generate them.

If I disparage you behind your back, I’m doing you a wrong, even though you don’t know about it. If I disparage you after you’re dead, I’m still doing you wrong, though you’re no longer around to be hurt.

Our job is to take ownership of each others’ digital remains and treat them with human dignity. The model Öhman holds up for us to emulate is Max Brod, tasked with deciding what to do with manuscripts left behind by Franz Kafka, who wanted them destroyed. In the end Brod decided that the interests of “Kafka,” the informational body constitutive of a person, overrode the interests of Franz his no-longer-living friend.

What to do with our digital remains? Öhman’s excellent reply treats this challenge with urgency, sanity and compassion. Brod’s decision wasn’t obvious, and really all you can do in these situations is to make the error you and others can best live with.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply