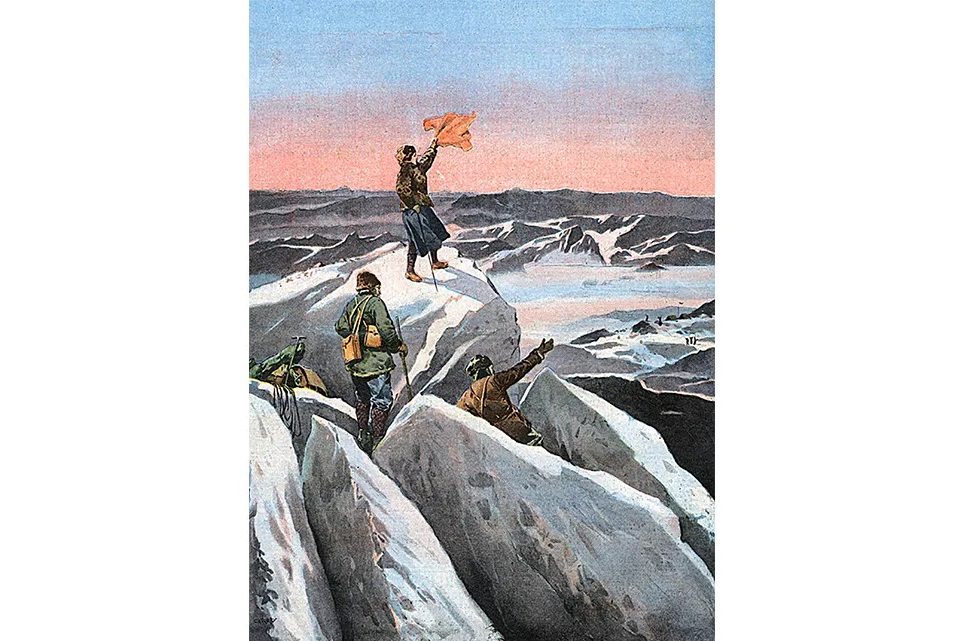

What makes men and women climb high? Most commonly, according to Daniel Light, “the prosecution of science or the advancement of empire.” It might also be general flag-waving or just personal fulfilment, as in the case of “private traveler” Godfrey Vigne, who opened his English eyes to the wonder of the Karakoram in the baleful 1930s.

London-based Light — “a keen climber, not a serious mountaineer” — has produced a colorful survey of mostly nineteenth century mountaineering across the globe, starting with the geographer and natural philosopher Alexander von Humboldt and his five-year expedition to South America. The baron came back convinced he had got within 1,000ft of the highest point on Earth, then thought to be Chimborazo in Ecuador, and told tales of a strange sickness that came on at altitude: vomiting, dizziness, shortness of breath and bleeding from lips and gums.

The White Ladder, Light’s hugely entertaining book, is divided into four sections, following four types of climbers in a loosely chronological narrative. They are imperial surveyors of Asia; sporting alpinists; “amateurs,” and the first to tackle Everest. The book ends after George Mallory vanishes “going strong for the top” — so before Sir John Hunt and the triumph of 1953. The author has a lot of fun as he makes his way up and down. In the closing paragraph of Part One he reveals:

The sport of ‘alpinism’ would bring a new urgency to the quest for the world’s highest peaks, personified by a man whose ego would eventually outgrow the mountains of Europe. He arrived with a bang, and his name was Whymper.

The tone is brisk, chummy and companionable: the reader feels safe on the end of Light’s rope. “There are fourteen mountains of 8,000 meters or more in the world,” he explains. “That’s roughly 26,250ft in old money.” Most lie along a 300-mile stretch of Nepal’s border with Tibet or in the Karakoram. Above all, the author showcases a beguiling gallery of characters. Albert “Fred” Mummery headed to India to bag the world’s ninth highest mountain, having knocked off all the trickier Alpine ascents. In 1895 he declared European peaks “overcrowded,” and ended up freezing to death on the slopes of Nanga Parbat with two Gurkhas.

Not all Light’s heroes sport iced-up beards. The American heiress Fanny Bullock Workman gets several chapters. She climbed higher than any woman had before, as well as lecturing at the Sorbonne and writing numerous travel books, such as her 1895 Algerian Memories: A Bicycle Tour over the Atlas to the Sahara. On the bottom rung of the white ladder is the detestable Aleister Crowley, busy even at altitude whipping the staff and pulling a gun on his tentmate.

As Light says, “no amount of imperial authority is a substitute for local knowledge,” and he pays tribute to the people who helped these mad white giants towards the top. Among them are 150 Balti porters who ferried provisions for Oscar Eckenstein’s 1902 expedition from Srinagar in lightweight wicker baskets called kiltas; the Kashmiri khansamahs who cooked the grub; and the Lepchas, Bhotias and, of course, Sherpas, “an ethnic group set to become synonymous with Himalayan mountaineering.” To many, the peaks held deep significance. Nanda Devi, “the bliss-giving goddess,” is believed to be the last refuge of a beautiful princess who dared to rebuff the advances of a Rohilla prince. She became the mountain, “its Devi or patron-goddess, and it is her eternal sanctuary.” A Tibetan translation of Kangchenjunga, “the most sacred of the eight-thousanders,” refers to five brothers who guard treasure stowed within its topmost snows.

Avalanches, cannonades, bivouacs, edelweiss and knapsacks… Light is above all a storyteller, and anyone who loves mountains will enjoy this book, especially if they prefer to experience the rasp of thin air from a base-camp armchair. On December 25, 1896, high in the Horcones Valley en route to the 22,837ft Aconcagua, Edward Fitzgerald and his team ate Irish stew straight from the tin, “slowly melting lumps of white frozen grease into our mouths and then swallowing them.” “Merry Christmas!” they said to one another. Robert Godwin-Austen calculated the position of his seventy-seven-strong team as they slogged up the Chiring glacier, a day’s march from the Mustagh Pass between Kashmir and Chinese Turkestan, by observing the boiling point of water, which drops half a degree below 200° F for every 500ft above sea level. One can’t help thinking this might have impeded progress.

The White Ladder is a collection of mostly jolly tales bound together with folksy sentiment, like this one, with which Light concludes his endeavor: “There are no real endings to mountain stories. Beyond one summit stands another. And death, the epilogue of one adventure, soon becomes a prologue to the next.” I wonder about that.