In Food for Life, Tim Spector’s book on the science of eating, the author gives the chemical makeup of a mystery food, listing more than 30 scary-sounding E numbers, sugars, acids and chemicals, before revealing that it is an… apple. Sally Coulthard’s book, The Apple, shows that it’s the apple’s complexity as well as its familiarity, that makes it the ideal punchline for Spector, and, for Coulthard, a perfect vehicle to carry the history of how we grow, trade, cook and eat together and take responsibility for each other and the environment (or not).

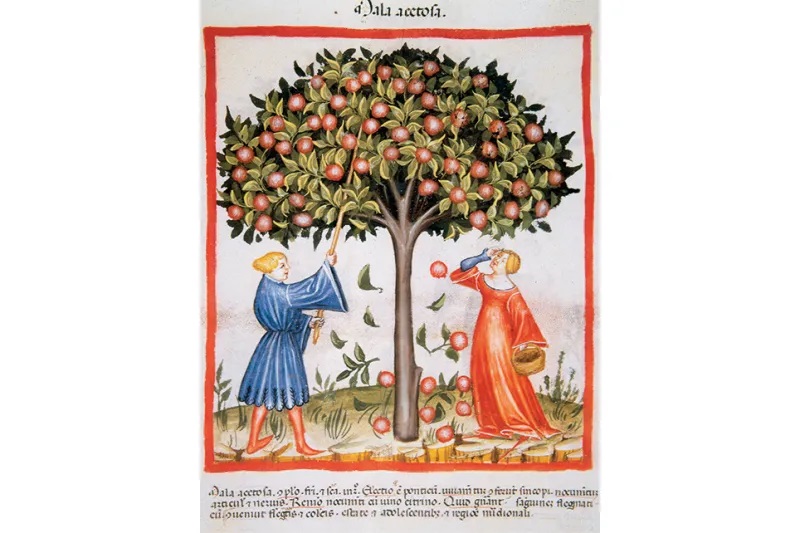

What we think of as an apple today – the sweet Japanese Fuji, the American picture-book Red Delicious or the sharper, Brit-friendly Cox or Bramley – owes its gamut of qualities to an easygoing readiness to adapt to local conditions. Coulthard’s story begins with the ancient ancestor of the Gala and Granny Smith, which hitchhiked west from the wild apple forests of the Kazakhstan mountains, promiscuously mixing with local crab apples along the way. The resulting hybrids produced fruit with qualities we still appreciate – sweetness and acidity, texture, disease-resistance and storability – and sweetened lives and flavored cultures as they traveled. Greeks, Romans, Norse and Celts rooted their fertility myths in the apple’s embrace. Milton retrofitted the apple to the Bible’s generic “fruit of the tree of knowledge,” making the most of the Latin malus for apple and evil.

The apple is core to our history. I make no promises the puns will stop there, because, as Coulthard shows, in this crisp and refreshing account, apples and humans have been through so much together, it is natural they should share a language too. They crop up in surprising linguistic by-ways: Avalon is the island of apple trees; the old-fashioned hair grease, Pomade, was made from the pulp of apples; costermongers sold Costards, which pop up in Edward I’s fruit bowl. Coulthard appreciates the pun-ability. I enjoyed “In-Cider Trading” as the title of a chapter on the hard stuff.

She has a taste, too, for juicy and gently myth-busting stories. William Tell’s arrow-pierced apple originated not in Switzerland but in Persia. Even before James Lind discovered that lime juice cured scurvy, Basque sailors held the disease at bay with unpasteurized cider (heat kills Vitamin C). The American nurseryman Johnny Appleseed planted trees he grew from seed (as part of a land grab) because his Swedenborgian beliefs outlawed grafting; the seeds produced “spitters” – too sour for eating and, ironically, only good for making the ferociously alcoholic “applejack” which sat badly with his religion’s teetotalism.

It is an easy book to chomp through, thanks to the cheerful prose and a structure that fruitfully grafts themes on to chronology. The taste and feel of the subject comes closest in the generous sprinkling of recipes from well-loved sources: dried apples from the Elizabethan writer on agriculture Hugh Plat; apple turnovers from the first American bestselling cookery writer, Eliza Smith. For all our contemporary obsession with recipe twists and innovations, we are oddly conservative with the apple in the kitchen. We have lost the knack of reducing apples down to the intense spread Jane Austen knew as black butter; or bringing a dash of sour with verjuice from crab apples; or floating “lambswool,” fluffy roasted apple pulp, on a bowl of steaming wassail. Give me a Norfolk Biffin over chocolate at Christmas any time: the “great compactness of their juicy persons” can almost be felt on the tongue, thanks to this nicely chosen quote from A Christmas Carol.

Britain reached a pitch of apple obsession when imported fruit from colonies past and present began pouring into our hungry markets; and Gladstone, galvanized by the threat, successfully inspired generations of orchard planters. However, in the century since, we’ve done badly in pomology, and the global growth of apple-growing has an increasingly bitter taste, which Coulthard runs through in her final chapter, “Crunch Time.” Economic demands for mono-cultures, grubbing up ancient orchards for reliable, homogenous fruit zapped with pesticides and herbicides, is not serving either the natural world of the orchard or our food security well. China now out-produces the US by a factor of eight, by massively overusing pesticides. Meanwhile, Britain exports pesticides to low- and middle-income countries, containing noxious chemicals which are banned in Europe.

Coulthard came to the subject because she lives in a Yorkshire farmhouse where, in the 1840s, a young vicar set about planting an orchard which has survived to this day. I found myself wanting to know more about that rare orchard – its moss and blossom, the tang of its fruit. But, although the sensory experience of growing and eating is a little elusive, Coulthard is cheerful and informative company on every leaf of this charming book.

Leave a Reply