It’s a dazzlingly staged event that evokes the ancient theater, Italian operas, elaborately choreographed Busby Berkeley films and an open-air spectacle on par with WrestleMania at Caesar’s Palace. I’ve watched it knowing that as a small boy, I tugged on my mother’s blue jeans and asked a question informed purely by cinema: “Is Cleopatra the most beautifulest woman in history?”

“No,” replied mother, with a cigarette stuck between her clenched teeth. “Elizabeth Taylor is.” I was, of course, picturing Elizabeth Taylor as Cleopatra.

The event I’m referring to isn’t mere cinematic overindulgence; it is a monumental moment — six decades after moviegoers first saw it — which transforms a movie star into a deity. On May 8, 1962, after months of rehearsal, the scene was finally ready to be shot. It would last nine minutes. It would depict Cleopatra arriving in Rome to conquer the hearts and minds of its citizens and senate. The pageantry of the scene would soon dwarf anything Rome had seen in its thousand-year history. Director Joseph L. Mankiewicz was understandably anxious — he needed the footage to justify the film’s ballooning cost. The scene was to be designed by John DeCuir, who had spent months developing a Roman forum that was double the size of the actual one.

DeCuir’s forum would cost $1.5 million; constructing it so depleted Italian building supplies that more had to be imported. Hermes Pan, the choreographer known for his collaborations with Fred Astaire, was flown to Italy to pull off the most spectacular scene of his career. The script called for somewhere between 4,000 to 10,000 extras (depending on what you read), dozens of horsemen, chariots, magicians, flamboyantly outfitted archers, Watusi warriors, gold-winged dancers, trumpeters, human pyramids, girls on elephants, dwarfs, zebras and scantily-clad python dancers. Sic semper extravaganza: most of it was edited out of the final cut.

The scene’s star was a nervous wreck that day, according to costume designer Irene Sharaff. Between March and April, Elizabeth Taylor had become the leading lady in “le scandale,” as paparazzi zoomed in on her affair with costar Richard Burton. They filmed their first scene together in January 1962, but by March, the tabloids were reporting on their smoldering romance. Gossip columnist Hedda Hopper wrote that Taylor had “done more to degrade the women of this world than any mistress of any king.” As many as 30 million Americans read Hopper’s column. Elizabeth Taylor had become the serpent of the Nile.

In April, an Italian paparazzo named Elio Sorci hid under a car and caught the first picture of Burton and Taylor kissing (both married to other people; both in bathrobes). The same month the Vatican printed an open letter describing Taylor’s behavior as “erotic vagrancy.” The headlines about John Glenn orbiting the earth had been eclipsed by “le scandale.” Georgia congresswoman Iris Faircloth Blitch announced that Taylor had “lowered the prestige of American women abroad and damaged goodwill in foreign countries, particularly Italy.” At one point, Jackie Kennedy asked her publicist Warren Cowan whether the two stars would marry. This is the backdrop of the scene.

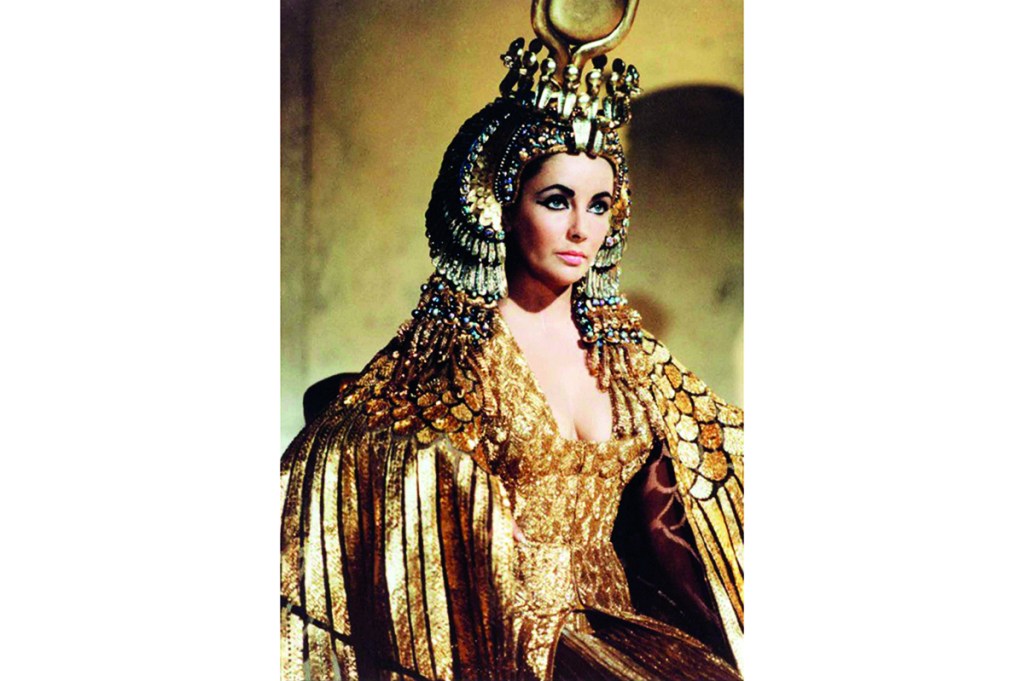

With Taylor bleeding across the headlines, lashed by the Vatican, there was a genuine concern that filming Cleopatra’s triumphal procession could result in the Catholic extras becoming violent. There were fears of an assassination attempt. It got so tense that armed guards blended into the scene to protect Taylor, who would arrive under the Arch of Constantine atop a golden float; behind her, there would be a thirty-five-foot-tall black Sphinx. She would be wearing a couture gold gown that morphed her physique into a mythological creature that merged the cobra with the phoenix — her crown decorated with ornate cobras forming around the erect wings of Isis (the costume was sewn with actual gold thread). When she passed under the arch, the crowd would chant:

“Cleopatra! Cleopatra! Cleopatra!” That’s how it was scripted.

The first time I watched the procession scene was on a wood-encased Magnavox TV that did nothing to enhance its visual splendor; even gorgeously shot Technicolor can look flat on an old tube TV. This time, sixty years after the film was released, I watched it on a fully restored, digitally remastered Blu-ray version that made the scene’s colors (gold, hot pink, vermilion, violet, stormy blue) burst off the screen like its most alluring special effect: Elizabeth Taylor’s face, this immaculate painting that nearly bankrupted its collector, 20th Century Fox.

Cleopatra cost Fox $44 million, making it the most expensive picture of its time. It forced the studio to sell off its backlot to foot the bill. When it became the highest-grossing film of the year — pulling in nearly $30 million in 1963-64 — it was still a financial failure.

The film’s stats are comically extreme: the wardrobe budget was almost $195,000 and included sixty-five different costumes for Elizabeth Taylor (a world record at the time). Fox had initially contracted Taylor for $1 million; making her the highest-paid woman in the history of Hollywood. There’s kitschy newsreel footage of her signing the contract, which included a 10 percent share of the film’s profits. Taylor would eventually earn $7 million for her work on the film.

She was paid, according to Hedda Hopper, in doled-out checks of $9,000 per day. She spent her time away from the set in a fourteen-room mansion in Rome called the Villa Papa. On September 28, 1961, Walter Wanger, the producer of Cleopatra, wrote that “Elizabeth is truly the Queen of Rome.” Taylor had also forced Wanger to use her Todd-AO 65mm film format, developed by her late husband, Mike Todd. The studio had become her servant. Cleopatra may have brought Caesar to his knees, but Taylor had practically cuckolded Fox.

Because of the aura of Elizabeth Taylor, the film’s couture gowns and exotic accessories, designed by Renie Conley, Irene Sharaff and Vittorio Nino Novarese, would shape the boho-chic trends of the sixties. Alberto de Rossi (the film’s makeup artist) designed the “Sphinx eyes” that Taylor would turn into a style trend: “If looks can kill…this one will!” was the slogan for the “Cleopatra Look” by Revlon.

In 1961, Taylor had become so ill with pneumonia that an emergency tracheotomy was performed to save her life. The tabloids reported that she had died. A month later, still convalescing, she would take home the Oscar for Best Actress for her role as a call girl in Butterfield 8 (1960). It was great PR for Cleopatra: The tracheotomy scar across her throat appears in the procession scene. “I was pronounced dead four times,” she told Vanity Fair. The scene would depict her rising from the ashes like a phoenix.

Cleopatra would become more of a scandal than a film, a celluloid backdrop to the paparazzi’s obsession with the lurid dalliance between Burton and Taylor. All the drama and decadence caused Life to call Cleopatra “the most talked about movie ever made.” The film itself caused hysterical reactions. It was as erotic as a Playboy magazine spread, campy when it needed to be melodramatic, delusional in its grandeur, more Beverly Hills than first-century BC. And all the time, filling the newspapers were photos of Burton and Taylor yachting off the Bay of Naples — which is why in the course of filming Cleopatra’s skin tone shifts between pale and toasted brown, which adds a dash of camp to the film’s aesthetic.

Cleopatra is, above all, an Elizabeth Taylor-worshipping vehicle. The procession into Rome is its apogee. I studied the scene like a paparazzo with a telephoto lens. I watched hundreds of slaves pull the sphinx in unison, slithering to the rhythm of Alex North’s exotic score. Liz Taylor is stoic, her physique a statue. She is as cold as an icepick. Her kohl eyeshadow glitters with diamond dust. Trumpets blare over heavy drums. The Roman senate is hypnotized. What is she thinking? Not Cleopatra, Elizabeth Taylor: heretic, homewrecker and perpetually divorced movie star. “Cleopatra was the most chaotic time in my life,” Taylor told Vanity Fair. “What with ‘le scandale,’ the Vatican banning me, people making threats on my life, falling madly in love… oceans of tears — but some good times too.”

She was thirty years old and at the height of her powers as a movie star; the procession scene was her red-carpet moment. When she slips under the arch, thousands of Romans applaud and scream like paparazzi begging for a glimpse of her face: “Leez! Leez! Leez!” instead of “Cleopatra! Cleopatra! Cleopatra!”

Hedda Hopper would later write: “She has become Cleopatra to the life now, and the world is her oyster. What she wants, she takes, come hell or high water — and this includes Richard Burton.”

The scene ends with Cleopatra descending from her float in complete silence. She is carried by sinewy slaves colored in black and gold. She pauses… bows to a rising Caesar… and the crowd erupts into rapturous applause and feral screams. I could have passed out right then and there, but then she raises her head, smiles, and winks at Caesar to remind him where the real power lies. It’s a shocking moment. It’s a wink she would rehearse with Mankiewicz; a wink that hisses with multifariousness: this is all a performance, nothing more than open-air spectacle, or maybe something more — a sly acknowledgment that while Cleopatra had conquered Rome, Elizabeth Taylor had brought the Pope to his knees. In nine minutes of masterfully choreographed veneration, Elizabeth Taylor (the movie star) becomes the only Cleopatra worthy of religious worship.

As she raises her gold-winged crown, we zoom into her voluptuous frame in a low-cut bodice that reveals what she describes to Caesar earlier in the film (somewhat ridiculously) as “breasts filled with love and life.” As she smiles with a restrained glimmer in her eye, with thousands of Romans worshipping her, Elizabeth Taylor blends the myth of Cleopatra with her movie star face: pale skin, heavy eyeliner stretched toward her ears, glittering eyeshadow, light-pink lips and scars depicting a woman more deified, and demonized, than Cleopatra herself.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.