We’re celebrating 250 years of circus this year. In 1768, the retired cavalryman and entrepreneur Philip Astley, together with his trick-rider wife Patty Jones (whose act was to gallop around the ring smothered in a swarm of bees) took a piece of rope, laid it in a circle on a piece of marshy land at London’s South Bank, and filled it with astonishing acts — tumblers, acrobats, jugglers, clowns. This was the very first circus. Every circus, anywhere in the world, began at that moment. The extraordinary new art form — a collection of street acts and horse tricks, infused with spectacle and risk and set in a circle — quickly trotted off around the world. It first sailed to Dublin, then spread throughout Europe and over to America, India and Australia. There has even been a circus in Antarctica. It’s Britain’s most successful cultural export.

Circus arrived in France in 1774, just six years after the first circus. French circus still flourishes, with an internationally acclaimed state-supported circus school in Chalons de Champagne and five circuses to appear concurrently this Christmas in Paris, one run by the book’s author. As Pascal Jacob points out, circus is an ‘intuitive diaspora’. A distinguished circus promoter and cultural historian, Jacob has donated his vast private collection to the French National Library. Most of the illustrations in this beautiful book — vibrant posters, architectural drawings of circus buildings and group photographic portraits of performers — come from there. These images are the stars of The Circus.

Controversially, Jacob begins his visual history not in 18th-century London, but in Mesopotamia and other ancient communities, ‘fascinated by balancing skills and great leaps in the air, feats of prowess on a tightrope or the skilful manipulation of objects’. In one of his many sweeping statements, as if throwing his arms out wide and calling the audience’s attention to the arrival of an act into the ring, he announces: ‘The history of humankind is in many ways characterised by the circle.’

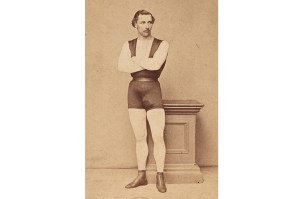

The book has a ‘mosaic effect’, which Jacob also identifies as the defining trait of a circus performance. He herds his facts like a ringmaster in a series of fabulous stories loosely held together by the arresting and colourful images. Some of the shiniest acts are the page-long portraits of circus characters that break in to the narrative: Jules Léotard (1838–1870), who invented the flying trapeze while wearing his signature tight-fitting bodysuit, giving his name to every gym outfit since (the song ‘The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze’ was written in his honour); Chocolat (1865–1917), a son of Cuban slaves who was fundamental in establishing the role of an auguste, a foil for the bossy white-faced clown; Sarrasani (1873–1934), born Hans Stosch in Berlin, who styled himself as a maharajah, wearing a bejewelled turban as he commanded 22 elephants; Claire Heliot (1866–1953), known as ‘the lion’s fiancée’ for posing regally on a throne, a lion’s mane on her lap, three more langorous big cats lying at her feet.

Around these jewels, the chronological history of circus is marked by milestones — the introduction of the menagerie; the construction of spectacular permanent circus buildings (only two remain in the Britain: the Great Yarmouth Hippodrome and the Blackpool Tower); the development of circus dynasties. But it is the arrival of the big top in 1825 that Jacob sees as the most significant. In the elaborate permanent circus buildings of the early 19th century, often resembling opera houses, horses lived in stables and the artists kept their costumes in dressing rooms. These buildings were an integral part of a town, not an interloper. But when circus became pop-up, all that changed:

The big top was a predatory presence. Seizing possession of an empty plot of land, it drastically disrupted the landscape… In the space of one night, land was turned over, long metal pegs were stuck in the soil, and a new, temporary city was erected… Such arrivals bore all the hallmarks of an intrusion.

These circuses constructed fences around their compounds, like a fortress. They were cut off from the surrounding community. They became more mysterious and enticing, but also more apart, and therefore menacing. Circus has remained in that liminal space since.

But don’t think all this wonder is history. I’m writing this in my caravan and, if I pull back my curtains, I can see the lights of the big top. My top hat waits on the table, ready for the ring. I can hear the music striking up now. The show goes on.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.