When a new book by an author often characterized as a conservative polemicist earns a rave review in the staid Economist, independent thinkers take notice. Christopher Rufo’s articles on recent US radicalism for the Manhattan Institute’s City Journal have long attracted wide attention, and now America’s Cultural Revolution has been praised as “meticulous” and “cerebral” as well as “persuasive and well-written.”

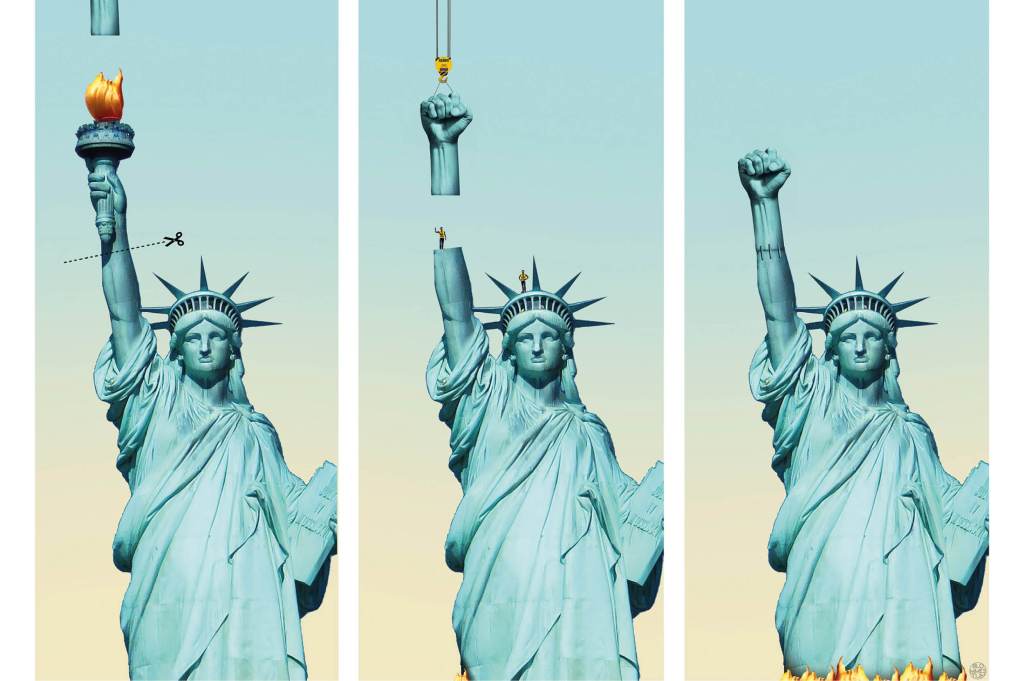

All true, for Rufo’s book is impressively erudite, reflecting a breadth and depth of familiarity with influential leftist writings that will shame any number of “woke” academics. Rufo seeks to expose “the historical development of the modern left and its ideological foundations” since 1968, and in doing so he identifies and richly profiles four seemingly disparate activist writers: philosopher Herbert Marcuse, black radical Angela Davis, educational theorist Paulo Freire and law professor Derrick Bell.

Marcuse may be a vaguely familiar name to many readers — more than Freire or, especially, Bell — but his insistent radicalism might surprise even those who read his best-known book, One-Dimensional Man, years ago. Marcuse called for a “dictatorship of the intellectuals” while also advocating “intolerance of movements from the right,” which “may require apparently undemocratic means.” His colleague Theodor Adorno accused Marcuse of encouraging “left fascism,” but Marcuse’s most famous teaching urged leftists to pursue a “long march through the institutions” by “working against the established institutions while working in them.”

As Rufo cogently details, starting in the 1970s, US academia became the uppermost target of the radical endeavor, and he quotes leftist historian Paul Buhle posing, and answering, the obvious question: “Where did all the radicals go?” after the New Left flamed out after 1968: “to the classroom.” It was in this crucial context that Freire’s work, especially his most important book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, played an especially influential role, for his “abstract appeals to liberation, revolution, and socialism have found a receptive audience,” Rufo writes, and have “had a profound influence in the United States.”

Nowhere has that been more decisive than among the faculties of American schools of education, which Rufo emphasizes “train the teaching force for American primary and secondary schools.” By inculcating racially-fixated identity politics in those teacher-training programs, critical race theorists “built a powerful transmission belt for their ideology, moving it from the universities into the public school system.”

Rufo argues convincingly that the overarching racial focus in present-day US academia, usually spoken of as “critical race theory,” owes more to the work of the late law professor Derrick Bell, who died in 2011 at age eighty, than to anyone else. I knew Bell for over thirty years, and taught his earliest law review articles to scores of students. Rufo quotes the heterodox black scholar Thomas Sowell as rightly observing that, into the early 1980s, Bell was “a sensible man saying sensible things about civil-rights issues that he understood from his years of experience as an attorney” litigating school desegregation cases in the Deep South during the 1960s for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

Bell joined the Harvard Law School faculty in 1969, but by the late 1980s his experiences in elite legal academia had led him to embrace what Rufo accurately terms a “relentless pessimism” about the prospects for black progress in America. “Racism is an integral, permanent, and indestructible component of this society,” he wrote in a 1989 book. Five years later, in a statement directed in part at one of his own black law school colleagues, Bell gave the lie to the widely-promulgated concept of diversity by declaring that “the goals of diversity will not be served by persons who look black and think white.”

The belief that there should be inherent limitations on how people think, determined by their skin color, represented a sad and pernicious descent for a lawyer who previously had devoted years of his life to litigating against white supremacist segregation. But Bell, a personally warm and charming individual — I saw him for a final time in 2010, eighteen months before his passing — attracted a gaggle of bright and articulate disciples, whose powerful writings eventually spread beyond the pages of law reviews.

For the better part of two decades, critical race theory had little footprint beyond law schools — and only a modest one within them — but over the past ten to twelve years CRT “has become pervasive in virtually every discipline in the universities,” Rufo writes. “The rise of critical race theory can only be described as an intellectual coup,” he adds, in a perhaps intentional double entendre, and he asserts that CRT would “change the face of American society” in the early twenty-first century.

The forcefulness with which Rufo argues his case — “there is a rot spreading through American life” featuring a “new nihilism that threatens to overwhelm the country” — can give one pause. Much of the work that critical theorists churn out amounts to little more than impenetrable, obscurantist jargon — consider “the imaginary power of commodified identities” or the “new structured mobilities and tendential lines of forces,” to cite just two examples.

Yet Rufo marshals important evidence to advance his case. Take, for example, Pew polling results from 2009 and 2017, bracketing Barack Obama’s presidency. When Democrat respondents were asked whether racism was a “big problem” in the US, in the earlier year only 32 percent said yes, but eight years later — after eight years of a black president — an astonishing 76 percent answered affirmatively, more than double the 2009 figure.

Rufo contends that such “Bellian” — my word — pessimism, indeed irrational pessimism, one might say, is the unsurprising result of how CRT’s fixation with racial identity politics spread beyond the universities during the Obama years. “The capture of the New York Times was a pivotal turn in the long march through the institutions,” Rufo writes, echoing Batya Ungar-Sargon’s perceptive 2021 book Bad News: How Woke Media Is Undermining Democracy.

Indeed, when it comes to race, Rufo memorably contends, the Times “accomplished what the Weather Underground and the Black Panther Party could not: persuade millions of Americans that the United States is a white supremacist nation that systematically exploits blacks and other minorities.” Rhetorical exaggeration? Not according to Pew, but then Rufo also points out how Derrick Bell himself once incisively noted “how easy it is to frighten whites.”

Over the past decade-plus, CRT has transmogrified into DEI — “diversity, equity, and inclusion” — across a widening range of institutions, not just universities and elite newsrooms. Rufo rightly labels equity “a deliberate obfuscation,” for the vast majority of Americans fail to grasp that for critical theorists and their followers that word “carries an entirely different meaning” than the far more familiar “equality,” signifying that “unequal outcomes of any kind” across racial categories are per se evidence of “systemic racism.”

Rufo emphasizes that DEI’s triumph has been primarily bureaucratic, as opposed to intellectual, for “hegemony is achieved not through ideological debate, but through administrative power.” Yet America’s Cultural Revolution concludes on a surprisingly optimistic note, for at bottom CRT is “empty professional class aestheticism, designed for manipulating social status within elite institutions” rather than bringing about actual social change for disadvantaged people of color.

“Critical race theory is, at heart, pseudo-radicalism,” he rightly argues, and its proponents are “parasitic, relying on permanent subsidies from the regime they ostensibly want to overthrow.” And, he predicts, “there will be a reckoning,” for “the simple fact is that the ideology of the elite has not demonstrated any capacity to solve the problems of the masses,” as was self-evidently true even decades ago when Marcuse and Freire first propounded their claims.

America’s Cultural Revolution marks Rufo as an important, deeply knowledgeable thinker, who merits the label of social critic rather than the inherently denigrating “polemicist.” And, thanks to the US Supreme Court, Rufo’s timing may in retrospect appear to be nothing short of perfect, for the landmark June 29 ruling in Students For Fair Admissions v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, declaring racially discriminatory affirmative action illegal, may in time come to be seen as what students of French history could call America’s racial Thermidor, the legal and political equivalent of 9 Thermidor Year II — July 27, 1794 — when France’s radically irrational revolutionary forces began to be vanquished. If so, America’s Cultural Revolution will be a book whose importance will only grow with time.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2023 World edition.