It is easier to say what this book is not than to describe what it is. It is not a biography, nor a work of musicology. As an extended historical essay it is patchy and selective. It is partly about pianos and pianism, but would disappoint serious students of that genre. It is not quite a detective story — though there are, towards the end, elements of a hunter on the track of his prey.

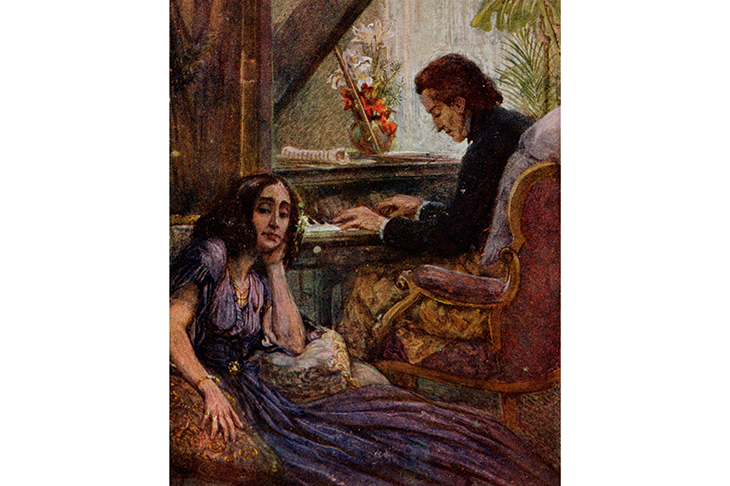

It is probably best to begin the book with no expectations of where it will lead. It starts in the Palma workshop of one Juan Bauza in the 1830s as he fashioned an upright piano — crude, even by the standards of the day — from local softwood, felt, pig iron and copper. This, it transpires, was to be the instrument Frederic Chopin would be forced to use in the brief stay he and Amantine Dudevant (aka George Sand) enjoyed — or endured — on Majorca in the winter of 1838–39.

Chopin had arranged for a more sophisticated Pleyel piano to be shipped out to the 13th-century abandoned Carthusian monastery in Valldemossa, but it arrived a few days before Chopin and Sand moved on. It was on Bauza’s instrument that Chopin was forced to compose some of his most beautiful masterpieces, including as many as ten of the Preludes. ‘It gives him more vexation than consolation,’ Sand wrote of the Bauza piano. ‘All the same he is working.’

So far, so good. The winter sojourn has been much trawled over before by previous biographers of both figures. Kildea notes elements of misogyny in the treatment — both contemporary and subsequent — of Sand. He muses on the French piano-building experiments of both Pleyel and Erard. He explores in some depth the structure and character of those Preludes thought to have been composed during this period and doubtless influenced by the one volume of sheet music — Bach’s 48 Preludes and Fugues — Chopin had taken with him. Kildea finds Chopin’s works enchanting and revolutionary: ‘In this collection of miniatures there is no throat clearing, no padding, no waste, no time to spare: the entire genetic make-up of each Prelude is present in the opening bars.’

We follow Chopin back to Paris. He splits with Sand, travels to England and back to Paris. By page 117 we have arrived in 1849 and Chopin is dead, yet we are barely a third of the way through the book. This, we are beginning to understand, is not a conventional biography.

Kildea’s focus now fans out in a number of directions. There is the subsequent history of the Preludes as compositions — did they lead directly to Debussy’s own works of the same name? — and in a tradition of performance (how much rubato?). There is the perennial question about whether Chopin is more French, more German or more Polish. We move on from Pleyel and Erard to the revolutionary innovations of Henry Steinway in devising an entirely new way of stringing a grand piano in the second half of the 19th century. The new pianos led to a different style of pianism. How, today, are we supposed to hear or perform Chopin on instruments so far removed from the more delicate and rudimentary instrument on which they were composed?

The pianism thread traces a line from Anton Rubinstein through Alfred Cortot to Alfred Rubinstein and Sviatoslav Richter. But Kildea takes a very large detour indeed to dwell on the Polish-French harpsichordist and pianist, Wanda Landowska (1879–1959). This is understandable, given her own parallel obsession with Kildea’s own quest. In her early thirties she retraces Chopin’s journey to Valldemossa to find — and purchase — Bauza’s piano which has sat, barely touched, for 70 years. The piano follows her back to Paris: we have a photograph of it sitting in her apartment, alongside her many other instruments.

Then, war.

Cortot — a mean, self-absorbed collaborator — comes to rule the artistic life of the French capital. Landowska flees to Spain and then New York. She makes a new life, beginning with the first dirty, battered upright piano she can lay her hands on. Meanwhile the Nazis helpfully catalogue, and then callously requisition, her own instruments and papers. The question of whether Chopin is more German, more French or more Polish becomes a more acute one.

After the war Landowska stays in New York, from where she launches a quest — it will take the rest of her life — to trace and recover her belongings. Kildea takes up the mission to track down the Bauza piano which had spent part of the war in Leipzig before being moved to Raitenhaslach in Upper Silesia. Kildea traces every rumour about the piano’s travels — including reported sightings in Munich and Florida. ‘There are long passages in Moby-Dick when we’re never quite sure Ahab will find the damn whale,’ he writes candidly at one stage of this prolonged search. ‘Hunting the Bauza piano feels a little like this.’

‘Perhaps the piano will one day show up; it seems impossible that an instrument of such hardiness and cultural potency should have been destroyed. Yet its disappearance is symbolic of a Chopin performance tradition that has vanished alongside it and which thoughtful musicians today attempt to track down. We must be patient on both counts — like Landowska in those final years, confidently anticipating Romanticism’s return.’

Chopin’s Piano is, in the end, an episodic, picaresque tale, woven confidently — at times even pacily — by Kildea. He writes knowledgeably and approachably about music and sympathetically about his cast of characters. It is the story of an obsession, but it manages not to feel obsessional. Even though — or perhaps because — I had no idea where it was going, I enjoyed it very much.