Sunjeev Sahota’s novels present an unvarnished image of British Asian lives. Ours Are the Streets chronicles a suicide bomber’s radicalisation, and its Booker-shortlisted successor, The Year of the Runaways, follows illegal immigrants in Sheffield — where Sahota now lives, having been raised in Derby by Punjabi-born parents. China Room, his most autobiographical work to date, mines his adolescence in deprived 1990s Chesterfield and imagines that of his great-grandmother in rural Punjab.

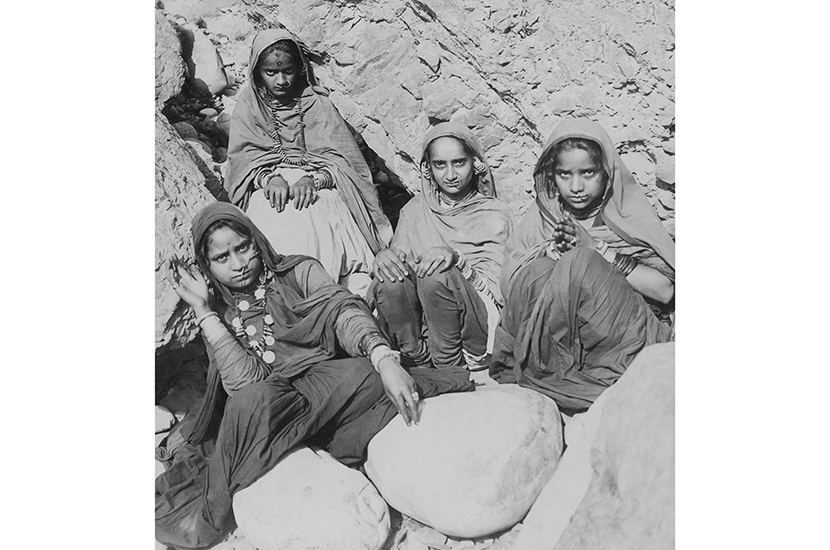

In 1929, a 15-year-old girl is married to one of three brothers. On a remote farm, Mehar shares confined quarters with the best china and two other veiled brides — each competing to conceive a son first. Couplings take place in darkness, at their Machiavellian mother-in-law’s behest, so the girls can’t tell which brother is their husband (this unsettling premise is based on Sahota family legend). There’s an erotic thrill when Mehar falls in love with hers, for any bond feels illicit in this claustrophobic atmosphere.

A fortysomething narrator’s memories are interwoven, echoes passing between the two threads. In 1999, aged 18, he arrives from northern England at his uncle and aunt’s house in Punjab, sick with heroin withdrawal, and then occupies the abandoned family farmhouse to get clean over the summer. Sleeping above the barred room his great-grandmother Mehar inhabited, he forges an unexpected friendship with Radhika, an alluring doctor on secondment.

Connections are transient, spun as much from imagination as from reciprocal feeling. Both past and present love stories count down to a departure, giving China Room its momentum. Sahota’s prose is a finely modulated instrument that moves from subtle minutiae to cosmic magnitude — ‘the animal’s black eyes seem to contain the night; perhaps the universe entire’. Its metaphors, drawn from the natural world, embody the latent violence of this ‘unkind house’: the teapot spout resembles ‘a cobra rearing back for the strike’.

Incarceration appears in many guises. The girls’ autonomy is stripped with dehumanizing completeness — at Mehar’s wedding, ‘she couldn’t walk, talk or hear’. Small-town life exposes outsiders to resentment and reveals the impact of politics on working-class lives. In 1929, Free India revolutionaries recruit fighters by force; in the 1990s, immigrants become scapegoats for an English community’s economic decline. As vanishing blue-collar jobs leave a void, Britain’s class system seems almost as rigid as India’s.

Exhibiting the narrative control and psychological acuity of Rohinton Mistry and Jhumpa Lahiri, Sahota’s tale of trans-generational trauma is quietly devastating.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.