The worst celebrity memoirists write first-person Wikipedia pages. Like Michelangelo carving a beautiful posterior out of Italian Carrara marble, the best celebrity memoirists edit their lives into tawdry yet moving epics. When they work, celebrity memoirs are the Warhols of American literature. When they fail, they’re the literary equivalent of a CVS receipt: boring and destined for the trash. Cher: The Memoir, Part One falls somewhere in between.

It takes a miracle to reach Cher’s narrative peak. For more than a hundred pages, she details her childhood criss-crossing America as her mom marries and divorces man after man. I lost track of how many jerks Cher’s mother married, but according to Google, she married six different men (Cher’s heroin-addict biological father twice). Cher breaks up the trauma monologue with page after page of going to Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. I like reading personal accounts of going to the movies; however, Cher reveals little about seeing Disney’s Cinderella, other than that she wanted to be a princess like a million other little girls. OK, Cher, get in line.

Later, Cher claims she dated different boys each week of high school because she saw herself as Holly Golightly from Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Ungallantly, while reading this section, I wondered, “Isn’t it more likely you’re a slut because you’re mirroring your mother’s serial marriages?” The most compelling childhood incident is one Cher omits. Early in her life, her mom dumps her at a Catholic orphanage. Instead of blaming her mom, though, Cher blames the nuns, which is in keeping with her struggles to admit how she feels about her mother.

But I felt for Cher, listening to the audiobook as I read the book. (Following Oscar nominee Michelle Williams’s rendition of Britney Spears’s The Woman in Me, publishers have treated celebrity-memoir audiobooks as an artform in their own right. To get the whole experience, you must indulge in both, which, of course, means buying it twice.) At points, Cher lets the Tony-winning actress Stephanie J. Block take over the narration of her mom’s misdeeds and other traumas. Cher claims it’s because dyslexia prevented her from reading the whole memoir, but I wonder if she was protecting herself from the hardest parts.

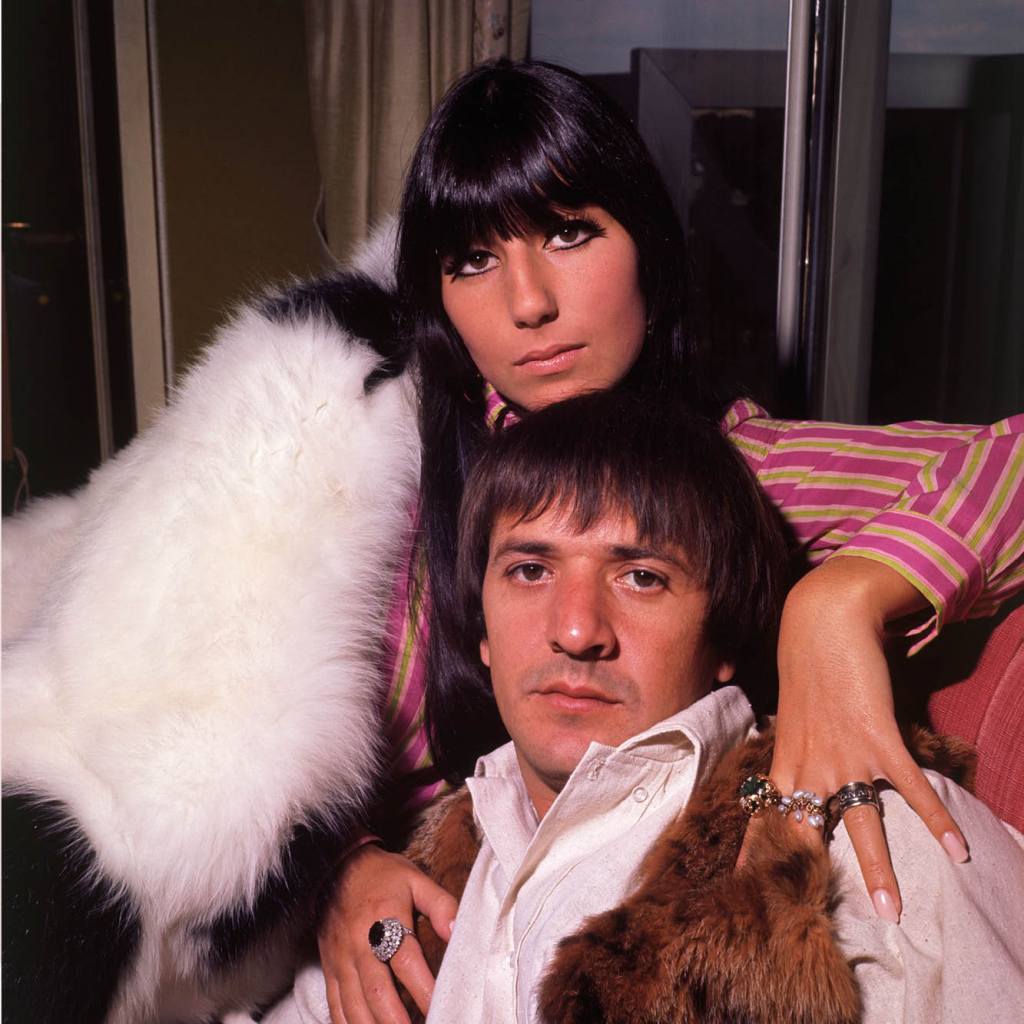

The saga of Cher and Sonny Bono, though, is a Hollywood story Cher can and does tell, and she tells it like the once-in-a-century relationship it was. Aged sixteen, she meets a then-unknown, already divorced single dad, Sonny Bono, at a restaurant. She moves in with him. He scores a job working for a new record producer named Phillip (you know him as the genius/murderer Phil Spector), and his teenage roommate tags along with him to work. One day, Darlene Love gets stuck in traffic, so Phillip pushes Cher into the recording booth with Sonny. Together, Sonny and Cher become the de facto back-up singers for future classics like “Be My Baby” and “Christmas (Please Come Home),” the style of which Spector called his “Wall of Sound” and critics deemed “teenage opera.”

Cher’s book comes to life in the Sonny sections. Like her acolyte Britney, Cher relied on three ghostwriters for her memoir. Unlike Britney and her trio, Cher and hers deliver details that linger in your mind. For days after I read the book, I wondered what Cher meant when she describes how she and Sonny lived in an apartment whose owner bought the building because they needed their daughter to stop being a stripper in Vegas. How does buying an apartment get a daughter off a pole? A good question, and one Cher never answers.

She does, however, explain the root of Sonny’s genius. America rejects Sonny and Cher as recording artists. Seeing the British invasion, Sonny moves his now-wife to England. His logic: they’re too cool for the States, so they need to get famous in Britain for Americans to accept them. They make it as hippie celebrities within days of arriving in London. They sing on top television shows, such as Top of the Pops, and Sonny and their publicists-turned-managers plant stories in the tabloids. (My favorite is the anecdote that a Saudi prince asked Sonny at the Playboy Club if he could purchase Cher.) The PR savvy continues in Los Angeles. When Cher goes into labor, the driver ensconces her in the back of her “ridiculous Rolls-Royce limousine” to drive her to Cedars Sinai. Sonny greets the limo and his pregnant wife with a camera. He knows the importance of images of a Hollywood nepo baby’s birth. Cher’s reaction: “I didn’t want photos of me thirty pounds heavier.”

The tweetable writing — Cher maintains a wonderful, inimitable X account — supports a timelessly romantic story that doubles as a Hollywood business lesson. Following the success of “I Got You Babe,” Cher and Sonny spend every dollar they make. By the time they figure out they owe the IRS over $200,000, they’re has-beens. Hippies are over. At the time, Cher hadn’t yet earned her reputation as, variously, a comeback queen, the variety act chick who would win an Oscar, a semi-forgotten grunge-era punchline, an EDM icon with the auto-tune landmark “Believe” and, naturally, as the star attraction of a never-ending farewell tour. Of comebacks, Cher writes, “I’ve done it so many times.” We know, darling, we know.

Coming back is harder than getting famous. Cher learns the ropes from Sonny. As they try to pay back the IRS, Sonny agrees to every interview, even on local news, where the couple pretends it’s an honor to speak to a nobody journalist in Philly. They play Las Vegas, long before Spears turned it into a get for A-list celebrities, where they develop a sarcastic, bickering-couple routine over a series of dinner shows. It works so well that they sell it to CBS as a variety show.

Cher is the star and chooses her designer, the future fashion icon Bob Mackie, while Sonny manages the business. He books tours. Against Cher’s will, Sonny pushes her to record an album in a week. Sure, TV variety shows are cheesy, but like once-and-future President Donald Trump, Sonny recognizes the power of trash entertainment as a launchpad to dominance. It is no coincidence that Sonny served in the House of Representatives and advised Speaker Newt Gingrich’s media strategy in the Nineties. Were he alive today, you can easily see Sonny at Mar-a-Lago as a member of Trump’s twenty-first-century royal court. But back then, Sonny wanted Cher to capitalize on their TV show. Cher hates his pick for lead single, “Gypsies, Tramps, and Thieves.” It becomes a global hit.

Business succeeds; romance dies. Sonny’s need for control pushes her away. In a riveting vignette, he confronts Cher in a Vegas hotel room. What does she want? She responds that she would like to fuck their low-level employee. “How long do you need?” Sonny asks. “Two hours.” He lets her fuck. Divorce ensues.

After they break-up, they continue to play the bickering but loving couple on television. Their act is so convincing that it works just as well when they hate each other offscreen. Their inevitable break-up is one for the ages. Sonny sends private detectives after Cher as she cruises through the San Francisco fog with the employee she’s banging. To her horror, she discovers she signed a contract giving Sonny rights to everything they’ve done, including full ownership of Cher Enterprises. She, meanwhile, makes a pitiful salary. Her new manager/gay boyfriend, David Geffen, gets her out of the contract, but Cher is broke. Once again, she reinvents herself, this time as a solo star. It works. Just as I lose count of how many men Cher’s mom married, relying on an abacus to keep track, I am unable to work out how often Cher loses her fortune, forcing her to stage a comeback. No wonder, twenty years after her “farewell tour,” she is still performing.

After the court finalizes Cher’s separation from Sonny, the memoir sputters. The final two chapters detail tabloid rumors that Cher injects heroin, Cher marrying (then regretting marrying) heroin addict Greg Allman (of the Brothers) and Cher longing to act on the silver screen. The details may seem tawdry, but they bore us because Cher fails to connect them to her life. Her dad was a heroin addict, yet she seems unable to spot the connections between Greg and her father.

She concludes the memoir with what she considers a cliffhanger, and what readers might consider a mild tease. Her friend Francis Ford Coppola tells Cher if she wants people to see her as a serious movie actress, she needs to head to New York. Cher expects us to wait a year to buy Cher: The Memoir, Part Two. It’s the Wicked of pop literature. Still, Cher’s final chapter is no “Defying Gravity.” Cher may have wanted to act in movies, which undoubtedly meant something in 1980. But today, movies mean less than they did. (Do Gen Z kids even know what movie stars are?) There are better stories to be told, and as I close the book, I think of what I want to read in the next book. After Sonny dies, Cher remembers her love for him and records her trademark song, “Believe,” which becomes her top-selling single of all time. She was — talk about a comeback queen — fifty-two years old.

Will this make it into the next book? Your guess is as good as mine. The evidence of this one is that Cher doesn’t know what makes her Cher. She doesn’t know what makes her compelling. It ends up that Cher needs Sonny after all.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s February 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply