You will doubtless recall the model villages of your childhood holidays: the cold rain beating down upon you as you wander, confused, from the 1:15 scale Stonehenge to the 1:18 Houses of Parliament to the 1:32 scale model railway, before sneaking your foil-wrapped sandwiches into the tea shop to share a pot of tea. Or maybe that was just me and the Queen, who famously visited Bekonscot model village in Beaconsfield as a child back in the 1930s, clearly the perfect day out for any monarch-to-be, to be able to survey a ticky-tacky kingdom made entirely of resin, foamboard and nostalgia for a past that even then had never really existed.

Simon Garfield’s In Miniature is a book not just about model villages, but also about miniature books and portraits, flea circuses, miniature battleships, tiny furniture, and architectural models — anything that is a ‘reduced version of something that was originally bigger, or led to something bigger, and… consciously created as such’. Despite its subtitle, it’s not really a book about small things but about scale. Indeed, not everything he discusses is small: Miniatur Wunderland in Hamburg, for example, boasts ten miles of model railway on its 7,000 sqm site housed inside a warehouse, and features no fewer than 260,000 figurines, thousands of which are apparently ‘kidnapped’ every year by visitors seeking souvenirs.

‘The miniature world is more than an artless conglomeration of miniature things,’ claims Garfield; ‘it is instead a vibrant and deeply rooted ecosystem.’ This far-reaching, rhizome-like ecosystem he traces all the way from the history of the Hilliard miniatures to the Miniature Book Society’s Annual Convention at the Marriott Hotel in Oakland, California, where he is tempted to buy a copy of the Shiki no Kusabana, a book produced by the Toppan Printing Co. in Japan, and which measures just 0.7 mm by 0.7 mm and consists of a single illustration of a flower with 22 pages of text.

He also travels to Las Vegas to visit the various mini-resorts, reveals the identity of the man who was the model for the character of the model-maker in W.G. Sebald’s novel The Rings of Saturn, and marvels at Queen Mary’s Dolls’ House at Windsor, with its Cartier longcase clock, its HMV fully workable wind-up gramophone, and its miniature jars of Frank Cooper marmalade.

In a series of short chapters, Garfield offers not just intriguing snapshots of curiosities but some rather interesting history lessons. Did you know that William Wilberforce used a miniature model of a slave ship to promote the anti-slavery cause? Or that H.G. Wells was an enthusiastic gamer who published not one but two books all about role-playing games for children and adults? In The Game of Wonderful Islands — apparently of his own invention — Wells explains that the purpose is to ‘land and alter things, and build and rearrange and hoist paper flags on pins, and subjugate populations, and confer all the blessings of civilization upon these lands’. Harmless family entertainment.

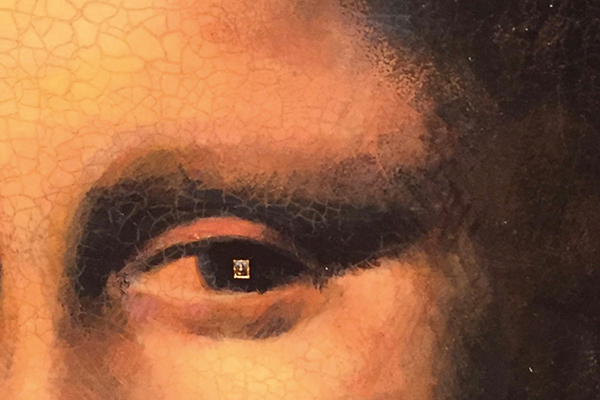

Garfield also interviews people working at the teeny-tiny cutting edge of the art of small things, including Mark McCloud, a curator of acid-blotter art in San Francisco, the artist Willard Wigan, the creator of micro-miniature sculptures, and — inevitably — Jake and Dinos Chapman, with their bizarro mini-tableaux. He also gives honorable mention to amateur miniaturists such as the Egyptian Hagop Sandaldjian, a musician and micro-modeler who specialized in carvings on grains of rice and strands of hair, and to the Vitel family, from France, who in the 1950s made a 70kg matchstick model of the Eiffel Tower, with full working electrics.

But the book is undoubtedly at its best when discussing model towns and villages. Though they can be found elsewhere they are, according to Garfield, ‘disproportionately’ a British obsession. In an era of instability and uncertainty, with an upsurge in nationalism and a backlash against globalization in all its forms, it is surely only a matter of time before we recognize our model towns and villages not only as national treasures but as symbols of our ambition to go it alone in a scaled-down world.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.