What connects pistachios, hay, and Mr. Krook in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House? Asked this question on a recent episode of the British TV quiz show Only Connect, the contestants noted all three are prone to spontaneous combustion, although, as one player exclaimed, “I can’t imagine that happening in a novel, but things were different back then.”

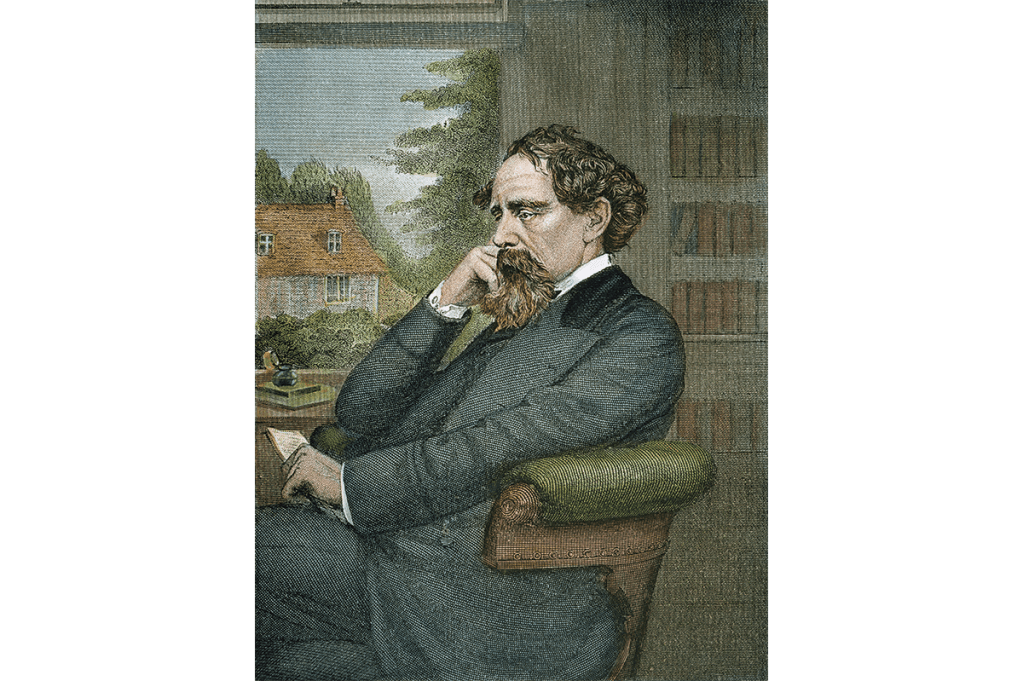

Novels contain novel imaginings, but people back then were equally skeptical. Dickens eventually had to defend the death of Krook, the sozzled owner of a rag-and-bottle shop, by listing the historical precedents. He knew a thing or two about a rapid reaction between fuel and oxygen that emits a fiery blaze of energy. By night he walked and walked, to still his beating mind. “If I couldn’t walk fast and far,” he said, “I should just explode and perish.” The heat and light radiating from his pages are the result of a combustible creative imagination for which the eminent scholar Peter Conrad has provided a new map.

Dickens the Enchanter is a patchwork of loosely thematic essays forming a series of night walks through a unique mind: shadowy, horribly restless, concerned with the devilish and the insane. This is not Dickens the cartoonist or Dickens the psychologist, nor yet Dickens the angry campaigner for social justice. These many guises are grouped within an otherworldly portrait of Dickens as some dark wizard, an “enchanter,” a “sorcerer,” the “Great Magician,” a “conjuror” – of worlds and words. Dickens becomes a tangle of Hamlet, Macbeth and Prospero: melancholic, haunted by ghosts, a magus of “traumatic” art. Magic, or just magic tricks? In life, as in art, Dickens didn’t shy away from bells and whistles. Conrad sees him as both designer and Foley artist, supreme at lighting and sound effects. Gaslight flares; lamps are extinguished; we hear the “Whirr-r-r-r-r-r-r-r” of a grindstone or the “tink, tink, tink, tink, tink” of a locksmith. But the old questions about realism in Dickens – whether his characters are a parade of flat freaks or a fair copy of human nature – are recalibrated by a study that shows him calling forth his own world, with its own reality. He called it Planet Dick.

Even in Hard Times, a short, sharp novel of Victorian industry far from the fairy tale invention of The Old Curiosity Shop or Little Dorrit, the description of a factory town is not a monochrome proto-Lowryscape. Instead, it is a wild vision, the river flowing purple, a piston rearing its head “like an elephant in a state of melancholy madness.”

As an insomniac, Dickens envied others their easeful unconsciousness, a state of mind over which he became obsessive. He populated his fiction with ghosts and revenants, animated the inanimate and made the living an incorporeal pile of limbs and clothes to be displayed: a row of wooden legs or a collection of waxworks in the curiosity shop of his pages.

Attending one of Dickens’s famous dramatic readings, the writer Charles Kent claimed that “character after character appeared before us, living and breathing, in the flesh.” Kent’s vividly nonsensical description is one step away from the modern, colloquial use of “literally.” For the only flesh was that of Dickens, increasingly weakened by the intensity of the performance. “His individuality,” wrote Kent, “altogether disappeared.” The conjuring blotted out the conjuror. Conrad’s book shows us a man blinded by his own glare.

Voices were Dickens’s speciality. When the original drafts for T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land were revealed in 1968, the most curious finding was a discarded heading from the poem’s opening section: “He Do The Police In Different Voices.” The phrase in question was soon found, in Our Mutual Friend, Dickens’s last completed novel. It was a line of Cockney slang, a music-hall turn. A babysitter, Betty Higden, describes living with her foundling assistant, Sloppy: “I ain’t,” she says, “much of a hand at reading writing-hand… but Sloppy is a beautiful reader of a newspaper. He do the Police in different voices.” In her precise and sloppy grammar – a careful twist of singular and plural – lies the astonishing fact of Dickens: a multiplicity that exploded from one god-like creator, in many voices and even in bad grammar.

Dickensian is a language, not an adjective. Conrad speaks it fluently. One of Betty’s foster children eventually dies in the arms of someone he calls “the boofer lady.” Sentimental, perhaps (“one must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing,” as Wilde notoriously quipped). But beauty, or booferness, has been in scant supply during the boy’s short life. The word is new on his lips; he and Dickens coin it together. Conrad never forgets that words, refashioned, heard anew, are the means by which Dickens saw the “romantic side of familiar things” – and, as this book argues, vice versa. Dickens heard how people speak, and, taking dictation, chafed against the strictures of “the English langwidge.” “Langwidge,” in his work, becomes phonetic stage directions for how to do the voices. Conrad helps us hear through Dickens’s ears, and listens to Dickens listening. In the acknowledgments Conrad thanks his publisher, “who understood at once what I wanted to do.” It took me a little longer, for the introduction does not set out the aim or scope of the book, and the blurb, which promises a “creative biography of [Dickens’s] life,” overlooks the fact that orderly biographical information is at a premium. Conrad read Dickens extensively through the Covid lockdowns. This is a feat of reading and remembering. Dickens’s prolificity is not irrelevant: the 15 major novels are made of nearly 4 million words. Conrad does not limit himself to the full-length works, incorporating biographical anecdotes and gleanings from the journalism, short fiction and correspondence.

He holds this great wodge of Dickensiana in his brain, or in a well-indexed set of notes, and flies about in it. Like Miss Mowcher, the diminutive chiropodist in David Copperfield, he is “here and there, and where not, like the conjuror’s half-crown in the lady’s handkercher.” He plays a good game of Only Connect with the obsessions and patterns, the occurrences and recurrences, to reveal the frightening and frightened mind at their center.

Untethered from chronology, what could such a study be but restive, a dragonfly exploration of a vast corpus? Vastness leads to claustrophobia, and the riches of Conrad’s book are not shown to best advantage when read for review, which is to say cover-to-cover and in long stretches. The text is a smog of names and quotations, seldom settling on a single book for more than a paragraph. A six-page analysis of David Copperfield appears like a comfortable bench on a vigorous walk. The writing falls into a fidgety structure that rarely lets up, continually positing an idea or noticing a leitmotif, and then providing a list of confirmatory examples. Page 103 is not unusual: “[Dickens’s] novels run through a prolific legion of names, pseudonyms and nicknames for the devils who make mischief in them.” Then we run through them: “in Dombey and Son… in The Pickwick Papers… in The Old Curiosity Shop… in Bleak House … Oliver Twist emerges… in The Cricket on the Hearth… In Little Dorrit… in Our Mutual Friend… in A Tale of Two Cities…” With synopses kept to a bare minimum, this parade could overwhelm anyone not already steeped in the material. For devotees the array of noses, umbrellas, wooden legs and so on will be familiar from John Carey’s great The Violent Effigy, “a study of Dickens’s imagination” to which Conrad’s lack of notes or bibliography permits no doff of the cap.

Dickens, Conrad argues, “found no respite from the inflammatory alarms of his own mind.” In this light – or gloom rather – the coincidences and sentimentalities of the fiction read as efforts to wrestle these dangerous imaginings into the safety of conformity and pattern, and the ringleted nymphets who pass for angels become a means of exorcizing the devils that stalked his pages and thoughts. He ran from his characters, but they gave chase. “I have been pursued by the child,” he wrote of Little Nell. He was doing the police in different voices, but those different voices policed his doings. Working on Bleak House Dickens felt his “head would split like a fired shell!”

Only such a head could have conjured Krook’s fate. This conjuror was good at vanishing acts: a puff of smoke, and abracadabra. Thackeray could have described a similar end for an epicure who drank to excess, but Dickens writes in another key. In his world London is built on dust and fortunes appear from nowhere before evaporating into the wind. The human soul extinguishes itself, leaving remains to be buried in overstuffed graveyards; houses are built on stilts and collapse into the streets; and shadowy characters called “Nemo” – no one – move, lost, through the fumes of industrial chimneys and vinegary opium. Even a hero such as David Copperfield is unnervingly soluble, dissolving into his own story to be remade by those around him, as Doady, Davy, Daisy or Trot. The combustion is not a satire of foible and gluttony but the invention of a man concerned by the light grip that Victorians had on an existence that had become tenuous, submerged by the fog of a newly industrialized, and newly godless, world.

Excellent on Dickens and God, and on Dickens as god, this dark and illuminating book gives us a figure observing from on high. Mr. Krook’s combustion occurs in those sections of Bleak House that are told, in the present tense, by an anonymous third-person voice, what Conrad calls the “omniscient narrator, an observer [offering] breezy surveillance of human confusion.” Yes, Dickens is always there, “in the spirit at your elbow,” unignorable. But on occasion he throws off his godly omniscience and plunges from his authorial crow’s nest straight into the pea-souper, as lost and blind as the rest of us. On the discovery of the greasy charred remnants of Mr. Krook, the third-person narrative combusts, and then splits – like a fired shell: “Oh, horror, he IS here! And this from which we run away, striking out the light…” The italics are mine, for in that “we” it is possible to see an author taking his readers and characters by the hand, running in darkness and fear from the red-hot cinders of his own invention.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply