There are about 7,000 languages currently spoken on this planet. By the end of this century, all but 600 will have disappeared — the inevitable result of an unstoppable process as the last speakers of the world’s little languages die out, usually leaving no trace, for the vast majority are spoken only, with no written record. But even languages which have had the good fortune to be written down face their own extinction as their individual writing systems struggle to survive. Hundreds and hundreds of unique alphabets, as much as 90 percent, face oblivion. Enter their gallant rescuer Tim Brookes, a British-born, Vermont-based writer, who is on a one-man mission, having set up his Endangered Alphabets Project in 2010 and is now offering this splendid sampling of some of the world’s threatened scripts.

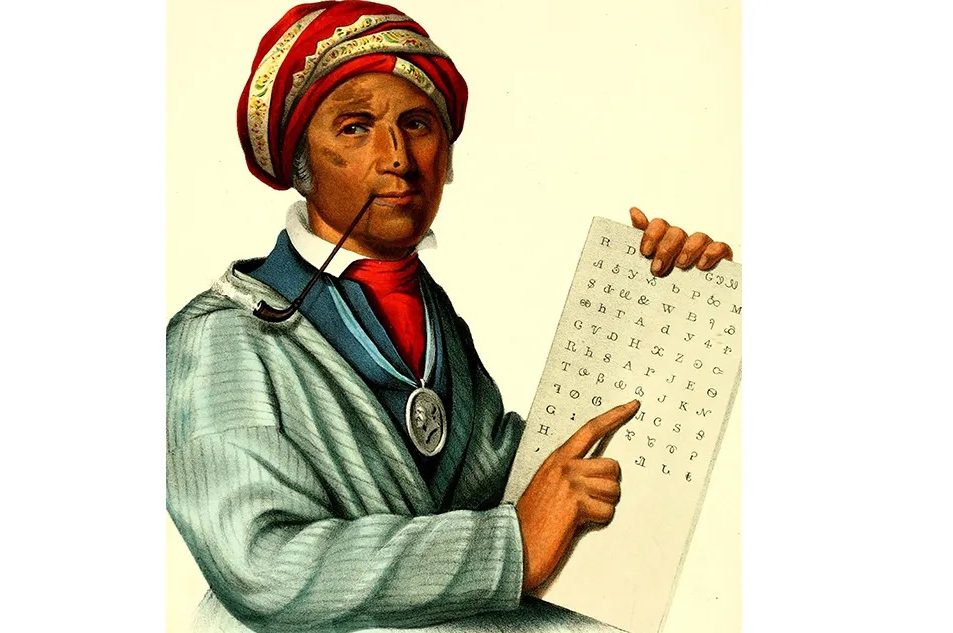

One calligraphic hero is Sequoyah, the Native American who devised a writing system for the Cherokee

They may be dicing with death but the weird and wonderful alphabets in this book do have the great advantage over ours of being written for the language they are recording. The price of the Latin alphabet’s dominance in Europe — and barring a few runes, that dominance has been total for the last 1,000 years — is that each language has had to fiddle, amend and bodge its written conventions. There are variations within each accent, of course, but the usual estimate is that English has between fourteen and twenty more vowels and consonants than there are letters in our alphabet. The result is that, for example, a serves for the long and short vowels in RP’s bar and cat; ch and ng are drafted in to denote consonants which have their own symbols in the phonetic alphabet, and th for the sounds in both either and ether. As for the much maligned glottal stop, that’s just completely ignored.

As well as being more comprehensive than ours, some of the scripts, in An Atlas of Endangered Alphabets, Brookes presents here carry a spiritual significance quite lacking in our resolutely mundane ABC. Many of these endangered alphabets are thought to have been divinely granted and some are practiced mainly or solely by shamans or priests. The Warang Chiti script used for the Ho language in eastern India starts with a letter representing om, the sound of the universe, which rather puts our a in the shade. The 1,500-year-old alphabet of the Mandeans, a much persecuted pacifist people who had the bad luck to live in Iraq and are now scattered throughout the world, is considered to be as holy as the words they represent in their sacred texts, with each letter carrying its own mystical meaning. In Vietnam, the script of the Cham language is taught in a four-day funereal crash course by priests to the dead so they can read and write in the afterlife.

There have been a few state-sponsored language revivals — notably for Hebrew and Irish Gaelic — but the ethno-linguists currently running round the Amazon rainforest and Papua New Guinea with notebooks and tape recorders are painfully aware that there’s really nothing that can be done to stop the ongoing process of language extinction. However, the prospects are brighter for many of the world’s threatened writing systems, thanks to the dedication of heroic individuals. These are men mostly, given that preserving or creating an alphabet is the kind of activity done by kids in their sheds. But a loud shout has to go out to one of the rare women mentioned by Brooke — Prasanna Sree from Andhra Pradesh who has come up with bespoke alphabets for nineteen of her region’s minority languages.

One of the earliest and most celebrated of this book’s lone calligraphic heroes is Sequoyah, the Native American who devised a writing system for his Cherokee people and language early in the nineteenth century. Overcoming ridicule, the widespread suspicion that he was dabbling in witchcraft and an arson attack by his disgruntled wife, who tried to burn down his cabin, Sequoyah persevered to create a script. He taught this with such success that within ten years the Cherokee had a printing press, a weekly newspaper and as many as 90 percent of them could read and write their own language — “a much higher literacy rate than their white oppressors.”

As Sequoyah discovered, setting letters into type and getting them into print has been a vital step for any new or threatened alphabet. Recent technology has proved hearteningly useful, with the internet hosting many dedicated websites and classes being taught on FaceTime and WhatsApp.

The enlightening text is accompanied by lots of examples, often one squiggle to a page, so that I can heartily recommend this book not only for calligraphy and language nerds but anyone looking to get an unusual, beautiful and quite possibly sacred tattoo.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.