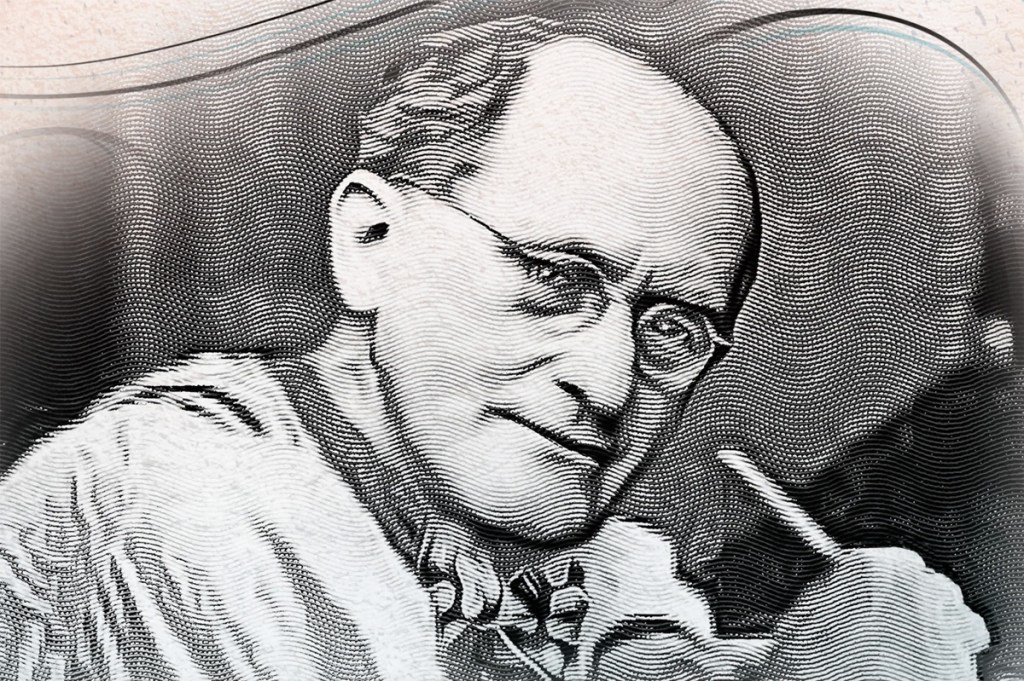

Bryan Garner has performed a remarkable act of cultural recovery with his vigorously written new book, The Etcher: The Life and Art of Oskar Stoessel, a long-forgotten Austrian artist who had total mastery of his form and deep understanding of the human face. Stoessel (1879-1964) attained success in the US in the 1940s after fleeing from the Nazis in 1938 with the help of US Minister to Austria, George Messersmith, who introduced him to elite American circles. Stoessel went on to etch portraits of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull, among many others, and exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC. He found his greatest supporters and subjects in the Supreme Court – he sketched all the sitting justices in 1941 and more in subsequent years. This association with the Court is the core of the book and of Garner’s interest. Despite such distinguished patrons, Stoessel eventually became reclusive, and moved back to Austria in 1960.

Garner is one of the leading experts on the English language and has revolutionized learning about grammar and usage through such essential books as the compendious Garner’s Modern English Usage (now in its fifth edition from Oxford) and The Chicago Guide to Grammar, Usage, and Punctuation. He is also a law professor and author of books on legal writing. His path to his discovery and fascination with Stoessel’s work was as a collector of jurisprudence memorabilia: In 2014 he purchased an etching by Stoessel of Justice Robert H. Jackson. Garner bought it for the subject, not thinking about the artist. A few months later, Justice Antonin Scalia, Garner’s close friend with whom he co-authored two books (and whom he wrote a memoir about), noticed the etching in Garner’s office and asked, “Who was Oskar Stoessel?” Garner didn’t know, but Scalia’s question led him on the path to find out.

Stoessel does not, as of this moment in fall 2025, even have an English Wikipedia page. Garner’s labor here was completely uphill. Such archival digs of unknown figures are not an easy sell, and Garner and his publisher have done a service by rescuing Stoessel’s art and social world from the void. Garner had to do some extensive trawling through correspondence of various Supreme Court justices, now held in the Library of Congress, to piece together the story of how Stoessel found work through and won the respect of these men. The Etcher kept reminding me of a similarly heroic recent book, To Anyone Who Ever Asks: The Life, Music, and Mystery of Connie Converse (2023) by Howard Fishman. Fishman recovers the unusual life of a long-forgotten original folk singer who (like Stossel) became reclusive and (unlike Stoessel) disappeared, yet who (like Stossel) left behind significant archival traces through her social circles.

Garner covers the process and history of etching, which held great prestige before photography – and long after among European aristocracy – but was falling out of fashion by the time Stoessel reached middle-age. Stoessel received rigorous formal training; he entered the highly selective Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna in the year that Adolf Hitler’s application was rejected for the second time. Stoessel sought a teaching position in the US after 1938, but despite his training and connections, could not find one. He lived with his wife in the apartments at Carnegie Hall, an affordable enclave for people involved with the arts. Garner notes that Stoessel did not seem to look beyond DC and New York for teaching work yet could have looked farther afield; the University of Southern California employed a professor of etching in those years. Stoessel’s younger brother, Ludwig, attained success in California, first as a character actor in movies and television, and then as “that Little Old Winemaker” in Italian Swiss Colony wine commercials.

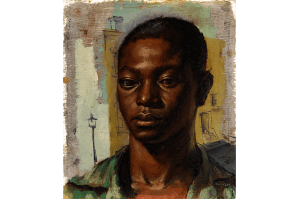

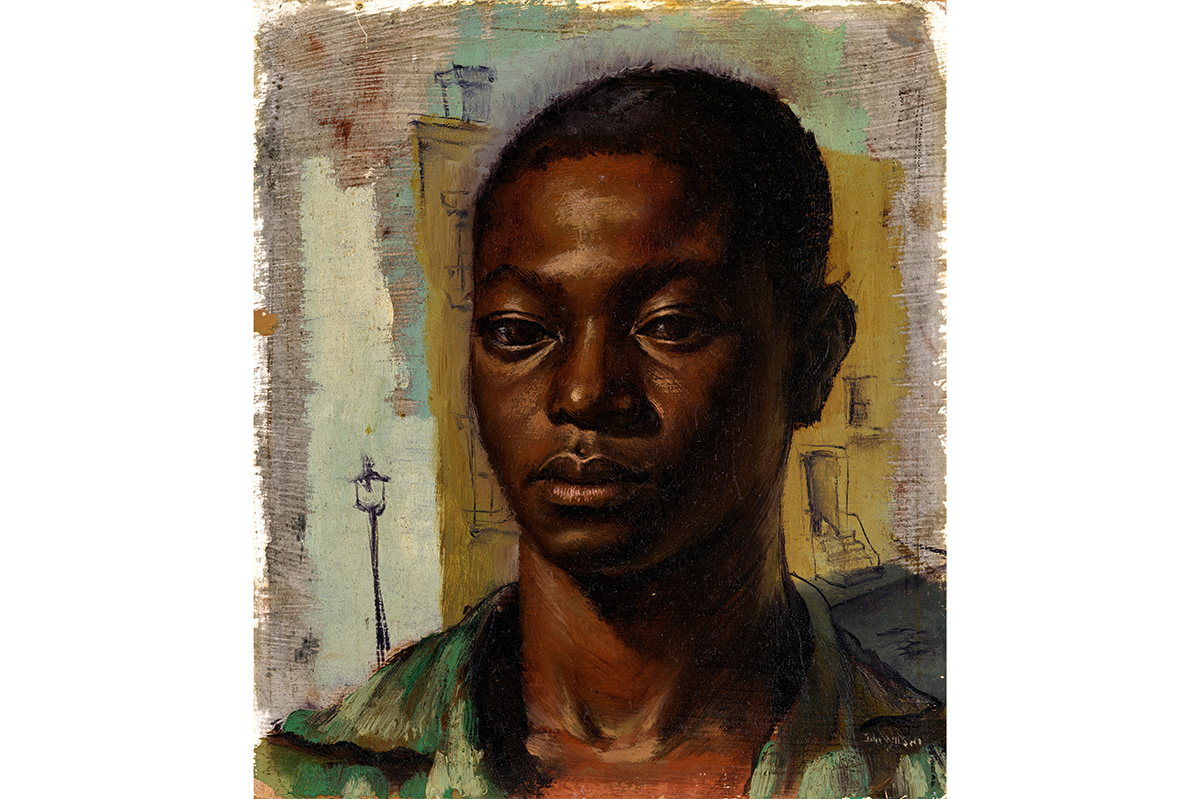

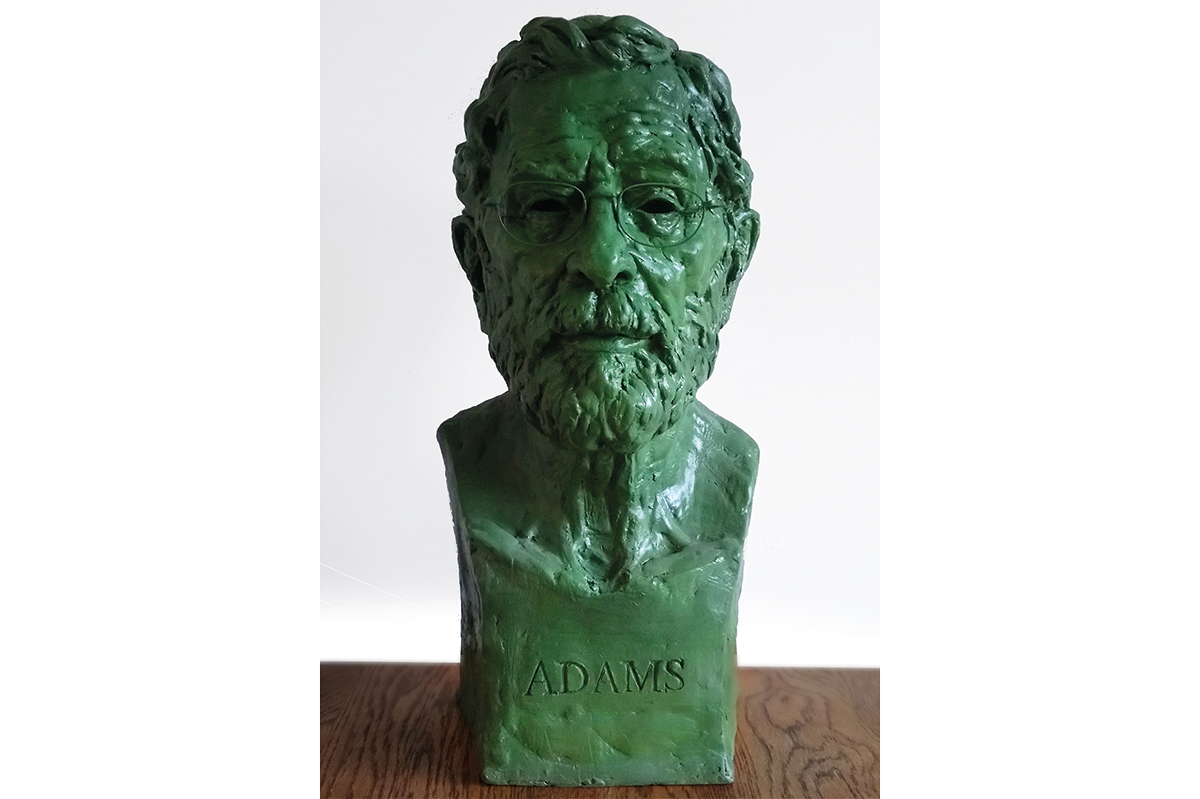

In addition to its biographical narrative, this is also an art book. It contains one striking, soulful etching after another. It’s unfortunate that the form went into decline – it would be nice to have more etchings of more historical figures. A master such as Stoessel seems to capture something that photography cannot. Stoessel also painted in oils, and the book includes a few of those – an oil self-portrait, as well as a stunning portrait of a young African American woman, whom Garner speculates may be Billie Holiday. I’m not sure about that, although it is not entirely out of the question. I think it is more likely that the sitter is the jazz pianist Mary Lou Williams. Another supporter of Stoessel’s was David E. Finley Jr., director of the National Gallery of Art from 1938 to 1956 and head of the “Monuments Men,” who donated four portraits by Stoessel to the newly established National Portrait Gallery in 1962. They were the first works accessioned by that institution. Garner notes that Stoessel, back in Austria by then, may not have known of Finley’s donation. The author writes, “People come and go in this world. Stoessel came and went. Messersmith. FDR. Hull. Stone. Jackson. Finley. Eleanor Roosevelt. They strutted and fretted their hour on the stage, and then were heard no more. Those with a historical bent know the names to one degree or another. They were famous, but fame is fleeting. Oskar Stoessel’s plunge into obscurity is particularly fascinating.” Indeed, it is.

Leave a Reply