Thirty years after it was first released in America, Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula is returning to theaters, appropriately enough for a Halloween re-release. (It also serves as a soft preview for Coppola’s newly announced passion project, Megalopolis, an epic drama starring Adam Driver and Aubrey Plaza.)

It is hard to overstate what a difference the past three decades have made in Dracula‘s popular reception. Although it was a significant commercial hit upon release, thanks in part to Annie Lennox’s enormously popular theme tune “Love Song For a Vampire,” it was critically derided as poorly acted, overblown, excessively bloody without being frightening and a travesty of the original novel. Few would have imagined it would linger in popular consciousness five years later, let alone thirty.

Today, in a very different world, Bram Stoker’s Dracula is regarded as little less than The Godfather of vampire films. It is Coppola’s last masterpiece (to date anyway, perhaps Megalopolis may yet change matters) and is worthy of comparison to his unforgettable triumphs such as Apocalypse Now, The Conversation and, of course, The Godfather and The Godfather Part II. Yet the key to its reappraisal is in understanding what Coppola was attempting to do in 1992, something bold and operatic and innovative, which, in its own way, paved the way for any number of regrettable imitators, from Twilight to — dear God — Fifty Shades of Grey.

The film’s genesis came, in part, from the frustrations that Coppola felt with The Godfather Part III. He had originally cast Winona Ryder in the role of Michael Corleone’s daughter Mary, but when she dropped out, citing nervous exhaustion, Coppola cast his own director Sofia in the part. It was a move that led to mockery and ridicule. Ryder and Coppola later met to clear the air, and Ryder mentioned that she had been given a script for a new version of Dracula, to be directed by the British filmmaker Michael Apted. Coppola, who had been obsessed with Stoker’s novel as a younger man, pulled every string in his considerable repertoire to be able to make the film, and assembled the cast to die for.

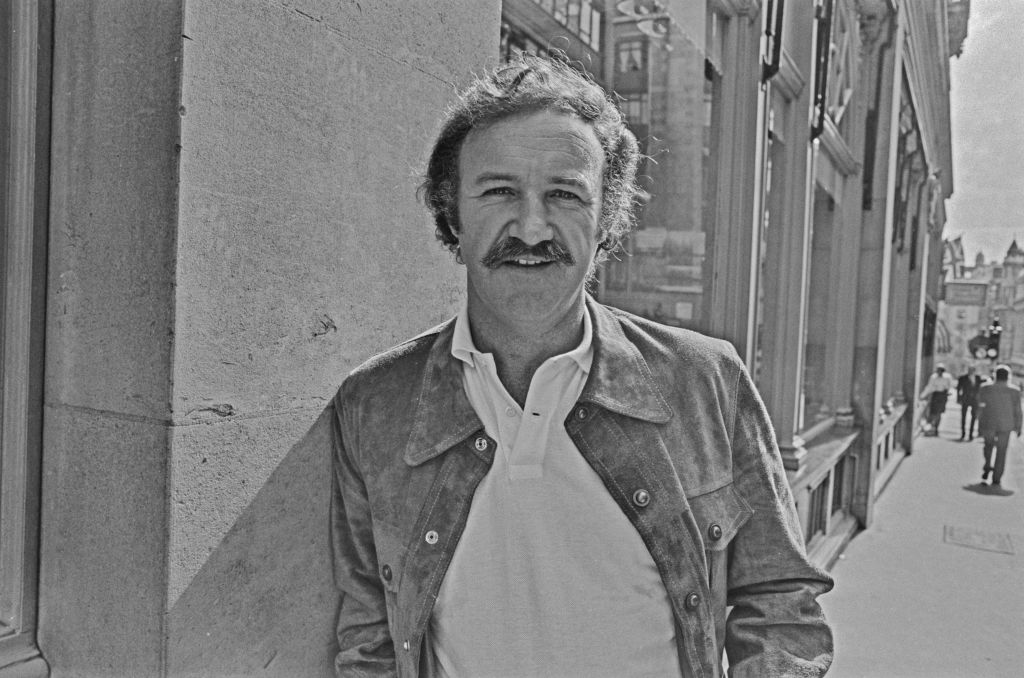

The intense British actor Gary Oldman was cast as Dracula, on the grounds that he could project the menace and charisma that Coppola wanted. Ryder would play Mina Harker, the reincarnation of Dracula’s true love Elisabeta. And Anthony Hopkins, fresh from winning an Oscar as Hannibal Lecter, took on the role of Dracula’s nemesis Van Helsing. A more controversial choice was Keanu Reeves, then best known for his roles in Point Break and Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, to play Mina’s fiancé Jonathan Harker.

Reeves’s heroic but doomed attempts at an English accent were one of the main causes of derision surrounding the film’s initial release. The presence of such fine character actors as Richard E. Grant, Cary Elwes and, as Dracula’s acolyte Renfield, the musician Tom Waits bolstered the project immeasurably, as would Coppola’s decision to film entirely on sound stages using old-fashioned special effects techniques. There would be no hint of modernity here, just the painstaking creation of a strange and disturbing world all its own.

As ever with Coppola, the production was troubled and expensive, with rumors that he verbally abused Ryder on set to get the suitably neurotic performance that he wanted from her. The relationship between her and Oldman also suffered, as the actress later said that she felt “there was a danger” in working with him. The Hollywood gossip machine decided the film would be another in the long line of Coppola’s grand, heroic failures, following The Cotton Club and One From The Heart. Early word asked why anyone would want to watch a long, bloody vampire film that was, at its heart, a Gothic romance.

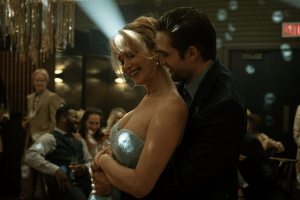

The answer, of course, was that the film was an enormous hit when it came out, restoring Coppola to the financial security that he has enjoyed ever since and bolstering everyone’s careers save for Reeves’s (he would have to wait for the likes of Speed and The Matrix for that). Seen today, it is obvious why Bram Stoker’s Dracula works so well. Coppola is faithful to the novel where he needs to be, but unafraid to bring in contemporary parallels too. Vampirism is clearly equated with HIV, and the central relationship between Dracula and Mina is swooningly romantic and played to the hilt by both Oldman and Ryder. In the film’s most famous line — it’s the reason Oldman took the role — Dracula declares, “I have crossed oceans of time to find you.”

This Halloween, it’s worth luxuriating again in a grand folly, one to marvel at and thrill to all over again.