This extraordinary summer of protest and upheaval has sparked the most pervasive and sustained interest in the question of what it means to be black in the United States that I have witnessed. The American people, it can be said in all earnestness, are finally having that proverbial ‘national conversation’ on racism. And yet, one of the more fascinating consequences thus far has been the emergence of White Fragility, a text written by the Italian-American academic and corporate consultant Robin DiAngelo, and How to Be an Antiracist, by the historian Ibram X. Kendi, as the two most sought after (by a wide margin) explanatory aids for understanding our moment.

Both books posit race — and racial difference — as something real and practically essential. Both books reduce the complexity of individual experience to membership in undifferentiated, monolithic masses defined by ancestry and skin color. For DiAngelo, whites as a category are inherently racist. There is a breathtaking circular logic that follows: to deny her proposition is to prove one’s racism, just as to admit its validity amounts to the very same revelation. For Kendi, not only white people but every single aspect of human affairs — each idea, policy or action — is either ‘racist’ or ‘anti-racist’ with nothing in between. Both of these enormous bestsellers introduce a kind of racial Manichaeism to the discourse that is religious in scope and fervor.

But there are many other texts — some recently published and some more and less forgotten classics — that offer alternative, nuanced visions. In my wildest dreams, these are some of the books Americans would reach for when the time demands a paradigm shift in our racial thinking.

Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life

By Barbara J. Fields and Karen Elise Fields

Imagine if we lived in a society where the book atop the bestseller lists in the wake of the killing of George Floyd was Barbara and Karen Fields’s criminally neglected masterpiece from 2012. What would that say about us and the world we wished to create? The sisters throw into question the entire black-and-white framework each of us helps recreate consciously and unconsciously on a daily basis. Two of their key insights are that the ideology of white supremacy is foremost a product of prior economic exploitation and that racism creates race — not the other way around.

The Omni-Americans: Some Alternatives to the Folklore of White Supremacy

By Albert Murray

Murray, a blues philosopher, novelist, genuine Renaissance man, lifelong friend of Ralph Ellison, and co-founder of Jazz at Lincoln Center, makes, with tremendous flair, the case that America is fundamentally a mongrel nation and that ‘any fool can see that the white people are not really white, and that black people are not black.’

Black Boy

By Richard Wright

For my money, the single best black male autobiography ever written. It is the template for everything that followed. Without Richard Wright, there is no James Baldwin.

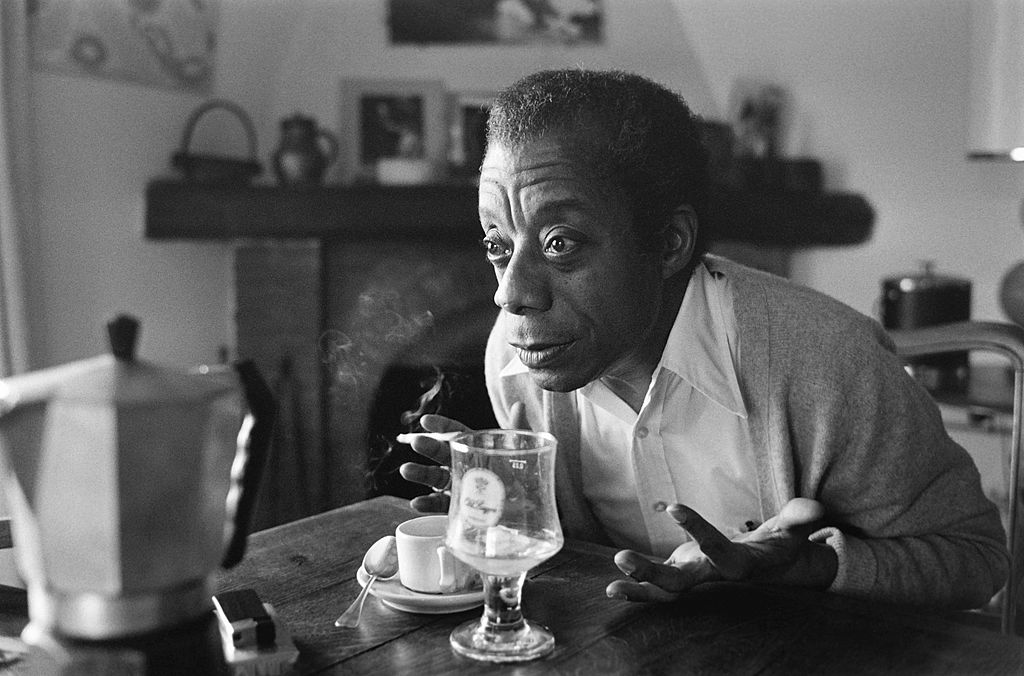

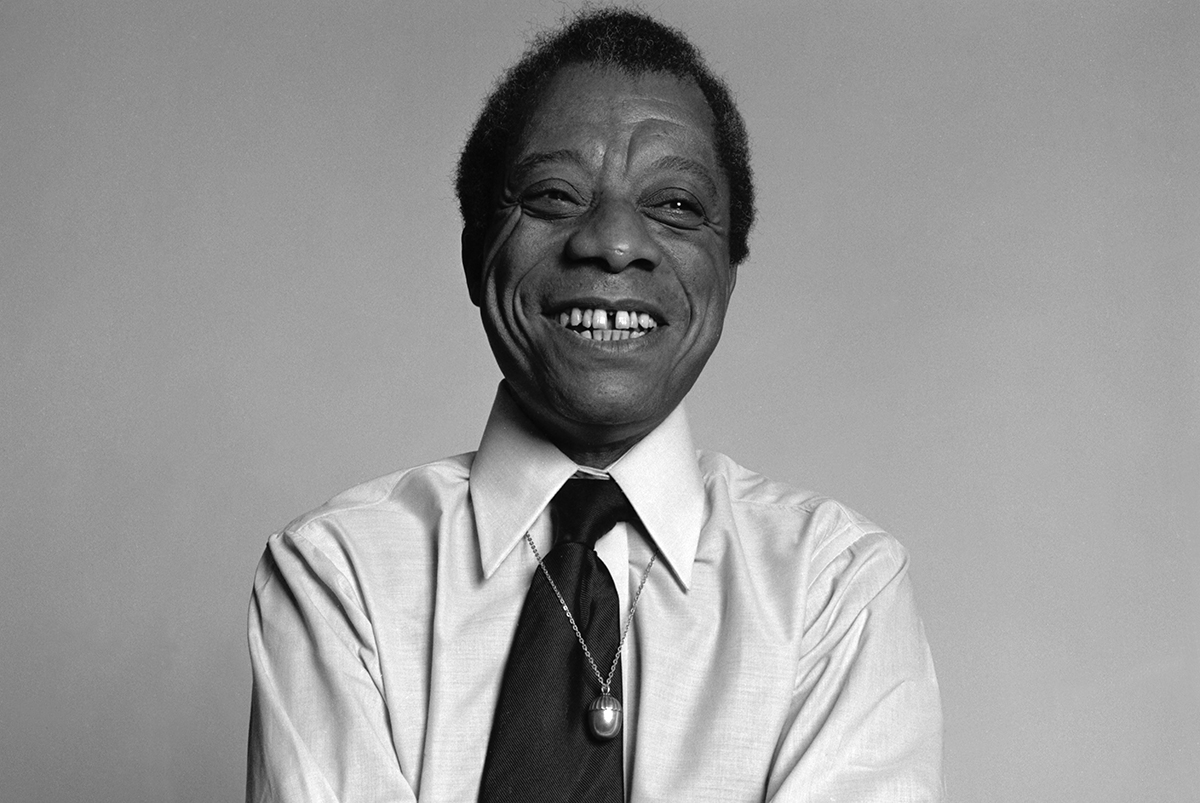

Notes of a Native Son

By James Baldwin

No one writes sentences like Baldwin — not in the English language. The greatest American essayist arrived on the scene fully formed. Notes of a Native Son, his debut collection, is suffused not with rage but with a clarifying tough-mindedness tempered into wisdom. His is a generous sobriety of which we are sorely in need.

Felon

By Reginald Dwayne Betts.

Betts is a polymath — a poet, memoirist, journalist and Yale-trained lawyer. His path to the life of the mind was less forgiving than others, wending through eight years of adult prison starting when he was still a minor. It has left him a genuinely fearless writer. The wordplay and structural inventiveness in this collection are astonishing.

Shadow and Act

By Ralph Ellison

Everyone knows Ellison wrote what many consider to be the greatest American novel — in that rarified air where only Moby-Dick and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn remain visible — with his sui generis debut Invisible Man. Fewer people realize he was also one of the 20th century’s finest essayists. Shadow and Act is a tour de force of precise and original thinking.

Writing to Save a Life: The Louis Till File

By John Edgar Wideman

A slim, unclassifiable and totally original evocation of the absurdity, intergenerational trauma and ontological stigma of the racial construct. This genre-bending account of the brief and terrible life of Louis (Saint) Till — the forgotten father of Emmett Till, the Chicago boy whose horrific lynching in Mississippi in 1955 helped spark the Civil Rights Movement — is the late-phase masterwork of, as Wideman once put it to the Paris Review, ‘a person who’s still scarred and outraged and mystified by the experience of Europe and Africa and slavery and the relationship between those continents.’

Survival Math: Notes on an All-American Family

By Mitchel S. Jackson

Jackson is an extremely talented novelist and born storyteller who, much like Betts, transformed his experience of incarceration into the subtle magic of art. His elaborately constructed portrait of life in Portland, Oregon provides one of the most bracing and sensitive glimpses into the contemporary intersection of blackness and poverty — and the indomitable spirit of the individual who will not be denied — that I have encountered in recent literature.

[special_offer]

The Souls of Yellow Folk

By Wesley Yang

The truth is that the subject of race in 21st-century America is far from simply black and white. Yang’s collection of elegant and staggeringly frank essays probes the complicated and liminal space in which Asian American identity is made and contested.