In the fall, a middle-aged man’s fancy turns to thoughts of death. As shadows lengthen, decay takes root in the raised beds, and the “spooky season” recalls the shortening of our days. It also provides an opportunity to reflect on how one artist embraced this time of year.

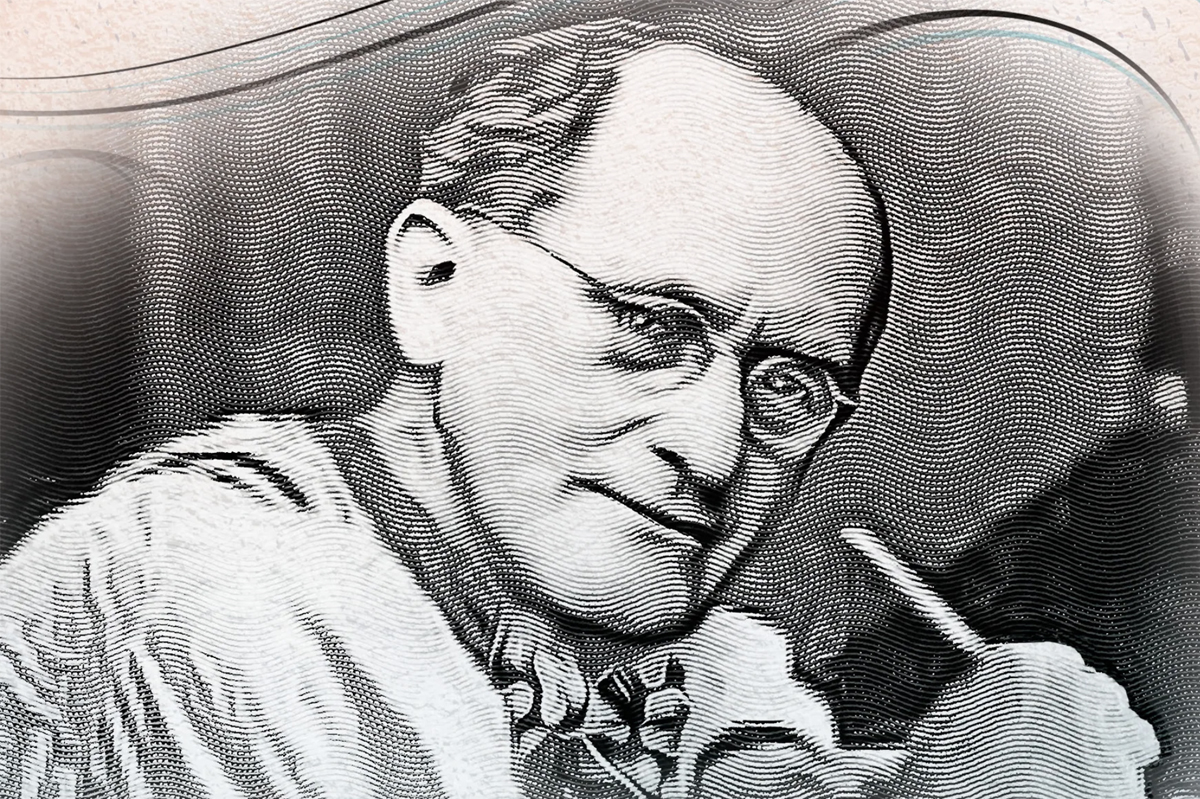

Much of the life of the Basel-born Symbolist Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901) was haunted by the specter of death. His first fiancée died before they could marry; he himself nearly died of typhus. Of his fourteen children, five died in childhood; three others predeceased him. His daughter Maria was buried in the English Cemetery in Florence, where Böcklin spent much of his life. Scholars believe that the cemetery partly inspired Böcklin’s most famous work, 1880’s eerie “The Isle of the Dead.”

The painting depicts an island shaped like a natural amphitheater, bathed in autumnal light and pockmarked by antique tombs. A grove of unusually tall cypresses stands at its center, while in the foreground a small boat approaches, bearing an oars- man, a figure dressed in white and a draped coffin. The artist never explained the meaning of this image, terming it “a picture to dream over,” but the dream in question was not solely the product of Böcklin’s subconscious.

When the American photographer Marie von Oriola visited the artist’s studio in 1880 and saw the painting in progress, she requested a copy but with the addition of some funereal aspect commemorating the death of her first husband. Böcklin obliged by adding the boat with its passengers and, struck by the result, went back to the original and included the same elements. On sending the completed picture, the artist enclosed a letter — with this work, he said, “you will be able to dream yourself into the world of dark shadows.”

For a time, “The Isle of the Dead” became one of the most famous paintings in the world, and Böcklin would complete five versions of it between 1880-86; a sixth, begun in the fall of 1900, was finished after his death by his son Carlo. Widely circulated prints of the picture furthered its popularity, so that by the 1930s novelist Vladimir Nabokov observed that reproductions of it “could be found in every home in Berlin.” Books and musical compositions were based on it and other artists created their own interpretations. The picture even inspired a 1945 horror film starring Boris Karloff, which director Martin Scorsese has called one of the scariest films ever made.

In his work, Böcklin often revisited the theme of death as perceived through the lens of the past. For example, in the richly colored landscape of 1877’s “The Elysian Fields,” a nymph and a centaur cavort beside a swan-filled stream shaded by autumnal trees. Despite its liveliness, the picture reflects death in both its foliage and its title. 1884’s “The Sanctuary of Hercules” captures the lonely feeling of a cemetery at the end of the year, with falling leaves caught up in cold winds. As in “The Isle of the Dead,” an embracing stone circle draws visitors into the memorial space.

You might conclude from these examples that Böcklin mourned the loss of the classical world, but the artist was contradictory on this point. “The ancients did not want to make antiquity, as far as I know,” he once scoffed, “only we want to do that.” Odd, then, that his morbid reflections are often deeply rooted in the past, even when he’s not depicting scenes from antiquity.

In his 1872 “Self-Portrait with Death Playing the Fiddle,” for example, the painter comes under the spell of a skeletal Death leaning over his shoulder, sawing away at the last remaining string on his violin. Though Böcklin wears contemporary dress, the painting recalls a much earlier memento mori portrait of the Tudor courtier Sir Brian Tuke accompanied by Death bearing a scythe. (In Böcklin’s day, the picture was attributed to Hans Holbein the Younger, another artist whose formation took place partly in Basel.) Like “The Isle of the Dead,” Böcklin’s image captured the imagination of many, including Gustav Mahler, whose widow later maintained that the painting inspired the second movement of the composer’s Fourth Symphony.

While for many years Böcklin’s work was hotly debated, today it is largely forgotten. The American art critic Clement Greenberg dismissed it as “one of the most consummate expressions of all that was disliked about the latter half of the nineteenth century.” Of course Greenberg, the self-anointed arbiter of kitsch, also believed that drop-cloth dauber Jackson Pollock was the greatest of all American painters, so at best his opinions should be considered as mere historical curiosities. Since each generation looks afresh at the art that preceded it, can we take a different approach to Böcklin, finding meaning where others find strangeness and irrelevance?

Perhaps Böcklin’s greatest strength lies in his unflinching take on the solitariness of death. Birth, childhood and adulthood are all shared experiences. Death, however, is the ultimate personal experience: even if you are attended at death, and later made the subject of funeral rites, mourning and obsequies, the last road is traveled alone.

Something to muse over, as you kick about the fallen leaves.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply