The fact that the master songwriter Bob Dylan is a fan of a literary allusion should come as no surprise. This is the man who, in his autobiography Chronicles Vol. 1, declared that reading the French symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud made “bells [go] off.” (Incidentally, it was Suze Rotolo, his first love whom he so cruelly lambasted in “Ballad of Plain D,” who introduced him to the poet. One feels that Dylan should have paid her a little more retrospective credit than the all-but-bitter love songs on The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.)

Rimbaud gets a name-check alongside his one-time tempestuous lover and fellow poet Paul Verlaine in “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go”:

Situations have ended sad

Relationships have all been bad

Mine have been like Verlaine’s and Rimbaud’s

But away from the stormy seas of symbolist poet’s love affairs (Verlaine and Rimbaud existed in a combination of poverty, opprobrium, and scandal, assisted by opium, absinthe, and hashish), Dylan’s literary interests do not pale.

Published in 1971 and written in the heyday of the ‘60s, Bob Dylan’s Tarantula is a prose-poetry attempt to ape the style of the Beat generation. High literature it is not, nor is it proof of a poetic talent that is able to sustain itself when unaccompanied by melody — but it is evidence that Dylan’s friendship with Allen Ginsberg was more than just good-natured bonhomie. In a 1985 interview, Dylan went as far as to say that “the Beat scene” had “just as big as an impact on me as Elvis Presley.”

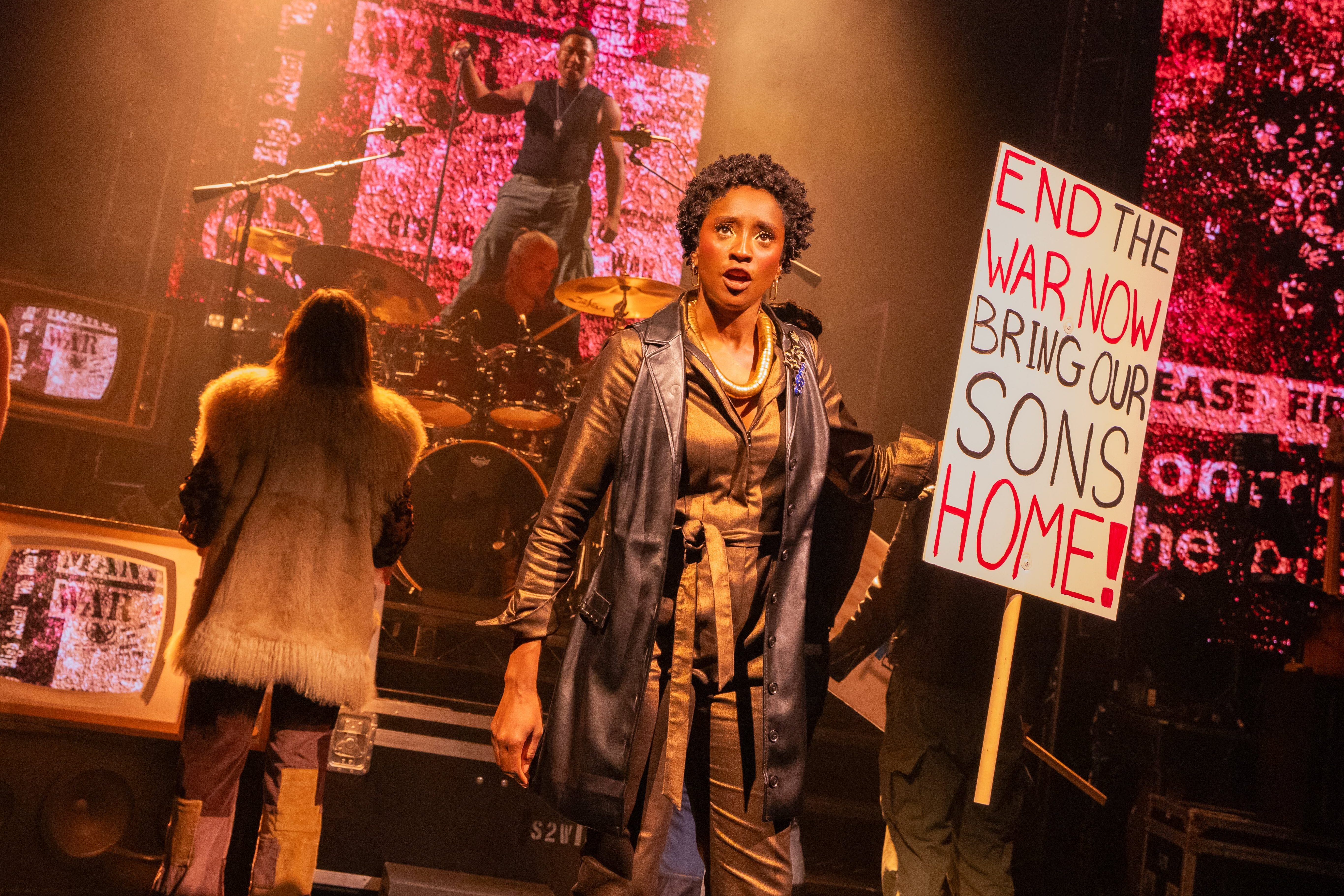

There’s something understandable, if not almost predictable, about Dylan liking the Beats: the freewheelin’ poets of love, sex, and a new world. This is, after all, the man who sang, “Your sons and your daughters are beyond your control, the old world is rapidly changing…” It is true that his songs are far more effective than their poems, but the fact remains that his half-truth-filled biography Chronicles is stuffed with tales of jumping on and off freight trains that would make even Dean Moriarty blush.

There’s similarly something that feels natural about Dylan reaching for the symbolist, Baudelaire-influenced lines and language of Rimbaud. What are the rambling, seemingly incoherent, intense descriptions of the scene in “Desolation Row” if not the hallmarks of symbolist poetry? Where else but in a Dylan song or in a symbolist poem could Ophelia beneath the window — “on her twenty-second birthday she already is an old maid” — and sit next to Cinderella with her hands in her back pockets “Bette Davis style”? The scene that remains — “the only sound that’s left after the ambulances go” — is pure evocation, rather than dull, tawdry sense.

But if Dylan wears his Rimbaud, Verlaine, and Beat influences on his sleeve, this is not to assume his reading is limited. To bastardize Whitman — and Dylan’s most recent album Rough and Rowdy Ways — he contains multitudes.

Only the other week, a collection of unpublished poems by Dylan were put up for sale. Written while he was at the University of Minnesota in 1959 or 1960 (despite what he claimed to some journalists, Dylan was not a penniless orphan), the young Dylan was trying his hand at the Beats’ style of free-verse:

Once upon a time there was

JUDY

And she said

Hi to me

Hidden among such moments of youthful prodigy (surely the Nobel Prize for Literature was already in his sights) is his description of meeting a woman for coffee and “flip[ping]” when “she / recited / all of Prufrock / By heart.”

T.S. Eliot is a well-known Dylan connection (he’s mentioned, along with Pound, in “Desolation Row” — the two men are “fighting in the captain’s tower / while calypso singers laugh at them and fishermen hold flowers). But here, for the first time, is proof that Eliot lingered in Dylan’s consciousness a long time before Highway 61 Revisited, and a while before he was even young and hungry in the music world. Just eighteen or nineteen, Dylan was — like so many bookish teenagers before him — obsessed with the famous poem that opens with the lines:

Let us go then, you and I,

When the evening is spread out against the sky

Like a patient etherized upon a table

Of course, once you start spotting Eliot links in Dylan, they’re hard to avoid — Christopher Ricks’ Dylan’s Visions of Sin does a masterful job of identifying them. And it’s tempting to become near-obsessed by individual examples. In “Tangled Up in Blue,” Dylan sings, “Then she opened up a book of poems and handed it to me / Written by an Italian poet from the thirteenth century.” Is this a reference to Dante? The poet whose presence is felt all through Eliot from Prufrock to The Waste Land and beyond?

But there’s a broader link to be made. Eliot is hailed as the poet of impersonality: he wrote, in 1919, that “the progress of an artist is a continual self-sacrifice, a continual extinction of personality.” Dylan, on the other hand, is hounded by critics and fans alike seeking to find the personality in his work. Is Joan Baez the woman at the heart of “It Ain’t Me Babe”? What about “Just Like a Woman”? Or the famously impenetrable lyrics of “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” — it must be about Dylan’s first wife, Sara Lownds. But what, oh, what does “My warehouse eyes, my Arabian drums” mean?

There is, of course, a debate to be had about whether Eliot succeeds in his “continual extinction of personality” (what is Four Quartets, with its “familiar compound ghost,” but an exploration of the personality of the poet?), but Dylan has never been given the chance. And despite how easy it is to mock his Beat-like pretensions or the failings of some of his later albums (there is one good song on Self Portrait and Dylan didn’t write it), there’s the undeniable truth that Dylan and Eliot were, in part, writing along those same streets of insidious intent.

Both tried — and try — to capture the truth of what lies around them, that overwhelming question of “what is it?”