This article is in

The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.

Once upon a time in the Seventies, rock ’n’ roll was a man’s game. Then Blondie happened –– or ‘Blondie’ herself, Debbie Harry, platinum bombshell and queen of punk.

Actually, before Blondie there was the Runaways, an exploitation act from which the singer, Joan Jett, ran away. There was Patti Smith, who moved to New York City, fell in love with Robert Mapplethorpe and wrote poetry. There was Chrissie Hynde, who moved to London, passed through the rehearsals that generated the Sex Pistols and the Clash, and then, after Blondie had charted in Britain, formed the Pretenders.

Smith and Hynde played the man’s game in men’s clothes. So did Joan Jett in her biker leathers. Hynde’s memoir, Reckless (2015), is mostly about survival and degradation: drugs, homelessness, the pill, rape. None of it was Girl Power material; most of it made people want to call the cops or a doctor, or both. There didn’t seem to be a Woman’s Way in rock until Debbie Harry’s frontwoman persona propelled Blondie to the crest of the New Wave.

The music was great, too. Blondie had the hooky tunes of guitarist Chris Stein and the drumming of Clem Burke, the Ringo of punk, but without Debbie Harry, they would have been just another garage band. With a dash of Marilyn Monroe, an eclectic look pulled from the secondhand stores and junk piles of New York, and those gorgeous smoky eyes, Harry inspired generations of female musicians with classics like ‘Heart of Glass’,‘One Way or Another’,‘Sunday Girl’, and ‘Call Me’.

Face It, based on interviews with journalist Sylvie Simmons, tells us what made it all happen, rather than how it happened. Harry is either too gracious or too lodged in her coquettish character to claim the credit she deserves. No, it was all, to use one of her favorite words, ‘synchronistic’.

‘I am a love child,’ she declares. Deborah Ann Harry was born Angela Trimble in Miami, Florida in 1945. When she was an infant, the family doctor told her mother that she had ‘bedroom eyes’. The illegitimate daughter of a plumber and a concert pianist, she was put up for adoption and raised by Richard Smith and Catherine Harry in Hawthorne, New Jersey. ‘Real American small-town living,’ she calls it. She ‘might have been oversexed’ in high school, but it seemed normal to her.

After high school, Harry moves to New York. Suddenly, she’s experiencing her ‘personal Sixties’, working in a head shop, getting ‘very turned on’ by a sexual assault from a photographer friend, trying LSD with Zen evangelist Alan Watts, and working as a waitress at Max’s Kansas City, where the Warhol crowd hangs out. She tries LA briefly, but finds New York is where her heart is. ‘So that’s when I became a Playboy bunny.’ Things go on like this for a while. ‘It was a more innocent time,’ she says about the drugs. ‘The stolen guitars hurt more than the rape,’ she says about a break-in at her apartment.

Then she falls for the New York Dolls. The shows are ‘sexy and fun’, and a respite from a stalker boyfriend from Jersey, but the Dolls’ glitter reflects a glimmer of aspiration: ‘I figure now that what attracted me so much to their shows was that I wanted to be just like them. In fact, I wanted to be them.’ At the time, Harry recalls, there ‘really weren’t any girls doing what I wanted to do’; even Patti Smith was ‘just doing poetry’. Chrissie Hynde felt the same way: ‘I can’t remember having sexual fantasies about getting it on with one of my rock-star heroes,’ Hynde writes in Reckless. ‘I wanted to be them, not do them.’

Soon, Harry is in a female-fronted group called the Stilettos, one of whose members has worked with Andy Warhol.‘It was an incestuous little scene,’ she explains. The smallness of the New York scene becomes a refrain; Warhol becomes a friend and later adds her to his gallery of portrait icons. At a Stilettos show, she meets a young man with long hair and kohl around his eyes, and a ‘kind of ripped-up glamour’: Chris Stein.

They become partners — romantically for 13 years, bandmates and friends for life. Their band — first Angel and the Snake, then Blondie and the Banzai Babies, and finally just Blondie — becomes a regular at CBGB in the Bowery, along with the Ramones and Talking Heads. In 1976, Blondie’s first tour, promoting their eponymous debut, is with Iggy Pop and David Bowie. Blondie really take off in the UK. British punk is ahead of the US, more physical and fun, and the Brits love Debbie. By 1978, the charming, half-French lyrics of ‘Denis’ have Europe head over heels for Harry too.

Finally, Blondie break America in late 1978 with the big one: Parallel Lines, which includes ‘One Way or Another’, ‘Picture This’, ‘Sunday Girl’ and ‘Heart of Glass’, the global disco hit that Stein calls ‘punk in the face of punk’. Two more hit albums follow in the next two years: Eat to the Beat, with ‘Dreaming’ and ‘Atomic’; and Autoamerican, with ‘The Tide Is High’, ‘Call Me’ (written by Harry and Giorgio Moroder as the lead song on the American Gigolo soundtrack),and‘Rapture’(America’s first rap Number 1, and the first rap music video to be played on MTV).

Yet the ‘suits’ at the label don’t get Blondie’s music. The band plays across the genres, never fully seriously, and they’re punks. Blondie’s first album is promoted with ads on Times Square showing Harry’s nipples. ‘Sex sells, that’s what they say, and I’m not stupid, I know that, but on my terms, not some executive’s,’ she fumes. She storms into the label’s office and asks how Mr Executive would like it if his privates were exposed.

Like Hynde and Smith, Harry finds few advocates for women in music. ‘I was just part of the game, a cog in the machine,’ Harry says. ‘You can pretty much sell anything when the corporate structure gets behind it and turns art into commerce.’ The art being punk music, and Harry’s image. And the commerce, in the days when singles sold into the hundreds of thousands, meant big money. ‘For a punk, this confrontation was a revelation.’

Fame is fickle, and so is New York in the Seventies. Sure, Harry is famous, but Blondie is dropped by its label multiple times, and the IRS takes everything. Harry and Stein keep finding themselves out on the street, once after an electrical fire destroys their apartment. Weeks after the fire, they return from a tour and survey the wreckage. Harry puts on a dress once owned by her idol Marilyn Monroe and grabs a frying pan. They do a photo shoot.

In 1983, Stein falls ill with pemphigus, a rare autoimmune disease. Harry tends to him throughout his years-long recovery. The band breaks up after six albums, and then, in 1989, she and Stein break up too.

‘Debbie blinked for two minutes while she was looking after Chris, and Madonna stole her career,’ Harry’s friend, director John Waters, said. Harry released solo albums and acted a bit. The band regrouped in 1997, but their wave had broken. Still, they kept going. They still are going: Pollinator was released in 2017.

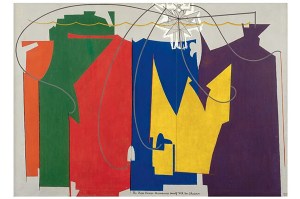

Harry has survived the ‘mental institution’ of the music business, as Bowie called it, seemingly unscathed. Her naughty schoolgirl jokes, (‘singing is hot and wet, and you can take that any way you want’); her endearing affection and respect for Stein; the inevitable and somehow logical narcissism of publishing fan art with her memoir: it’s as if a working 74-year-old artist is still that ‘oversexed’ high school girl, flashing her bedroom eyes: ‘It sometimes made me wonder if I’ve ever accomplished anything beyond my image.’

It’s all so innocent and effortless, and yet it wasn’t. Harry rarely talks about herself as a musician. It’s just business –– and yet it’s all fun. Harry is a charming paradox, a tell-all tease; or, as she puts it, a double identity, ‘half man, half woman’. Her early Blondie character was ‘androgynous’, a woman ‘playing a man’s idea of a woman’. Patti Smith dressed up as a boy, Harry says, but in early Blondie, she dressed like a boy’s idea of a girl: ‘My Blondie character was an inflatable doll but with a dark, provocative, aggressive side. I was playing it up, yet I was very serious.’

‘Blondie’ — Harry — became an icon because she was too smart, or too desperate, to rage against the machine. ‘I wanted to do music, and I didn’t give a shit if that meant being in a boys’ club.’ It was ‘demeaning, of course’ when the boys disrespected her, but sometimes, she says, ‘the sick punk in me felt flattered’. She has, she believes, been able to ‘turn that sexual disrespect around and make it work for me, rather than against me’.

Harry says that there’s no formula for succeeding in the music business as a woman. Yet she also says, ‘I have always thought the contrast between innocence and lusty sexuality, like that between good and evil, is irresistible.’

For Harry, it might be that simple. She swallowed the lifestyle whole — the drugs, the drag queens, the music. If that makes her at times a walking cliché and a bit of a blonde, it also makes her unstoppable, and a true punk.

This article is in The Spectator’s inaugural US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.