The Robbie Williams biopic Better Man opened in American theaters last weekend and, as every single box office commentator predicted, it flopped, and flopped hard. A gross of just over $1 million in its opening three days — less than the Golden Globe-winning The Brutalist, which is only showing on sixty-eight screens nationwide — is utterly disastrous, all the more so because this wasn’t a $10 million indie, or even a $40 million Rocketman, but a movie that it cost $110 million to make. A bold amount, many would suggest, when you are talking about a film that focuses on the life story of a British musician who is massive in his home country — probably the single most successful solo star there of the past three decades — and has a similarly enthusiastic following in Europe, Australia (which largely financed the film) and the Far East, but has failed to make any significant impact in the United States.

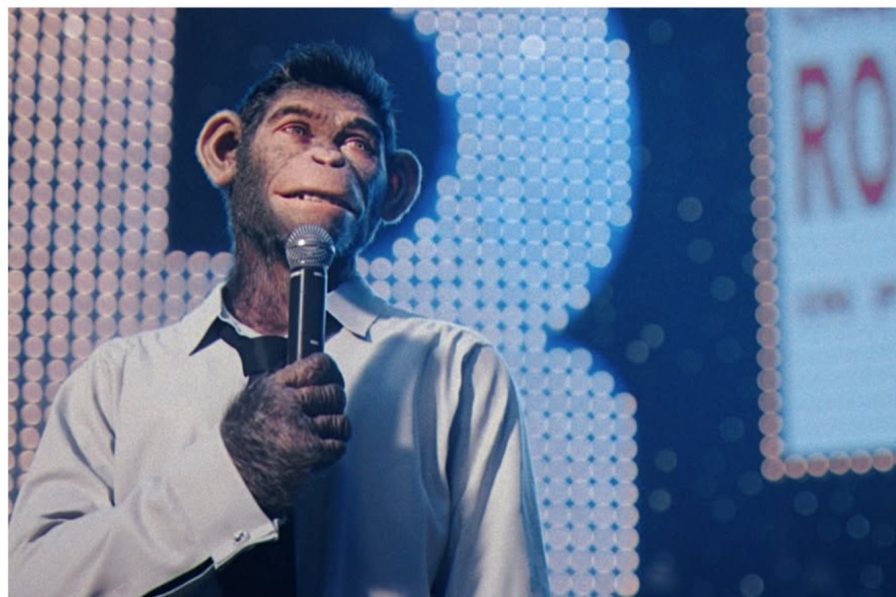

This is one of the reasons for its failure, but the other — and there really is no way of concealing this in the marketing — is that Williams is played by a photorealistic CGI monkey, which he largely voices himself. As soon as Michael “Greatest Showman” Gracey’s bold decision was announced, it was met with both incomprehension and ridicule. As if anyone was going to go and see that, especially in America. It would be nice to say that the naysayers were wrong, but the film’s failure has been total. It hasn’t been much more successful internationally either — even in Britain, where Williams routinely sells out the country’s largest stadiums — and seems fated to remain a cautionary tale, largely unseen and unappreciated.

There is a problem with this narrative, and it is this: Better Man is very good. Its central device sounds like a gimmick, and perhaps it is, but the decision not to have Williams played by, say, Taron Egerton, but instead to be represented in full, simian form is an arrestingly daring artistic decision that pays off remarkably well. At a time when virtually every other musical biopic demonstrates the “same old, same old” approach (hello, Timothée Chalamet as Bob Dylan! Come on down, Jaafar Jackson as Uncle Michael!), Gracey and Williams deserve kudos for doing something wholly different to everyone else. It should be noted that most people who have seen Better Man (mainly critics at this point) have raved about it, but unfortunately Paramount’s marketing failed to persuade people of its achievements enough to go and see it. Chances are that, tax breaks aside, it will go down as one of the biggest box office bombs of the decade. And that is not a fate that it deserved.

It is by no means flawless. The central dynamic, between Williams and his largely absent father Pete, is never as affecting as it should be, partly because of the casting of British TV veteran Steve Pemberton as Pete — he’s fine, but he’s not a dynamic screen presence — and partly because, as the film makes clear, the two were never fully estranged, meaning that the schmaltzy finale, consisting of the two duetting on “My Way” at the Albert Hall in London, may be briefly affecting but lacks the true emotional resonance that it ought to have. And sometimes the sheer onslaught of musical and visual pizzazz gets a bit much: this is a film that will make you believe that you suffer from ADHD, although it was never anything like as irritating for this viewer as Baz Luhrmann’s recent hyperactive, soulless Elvis.

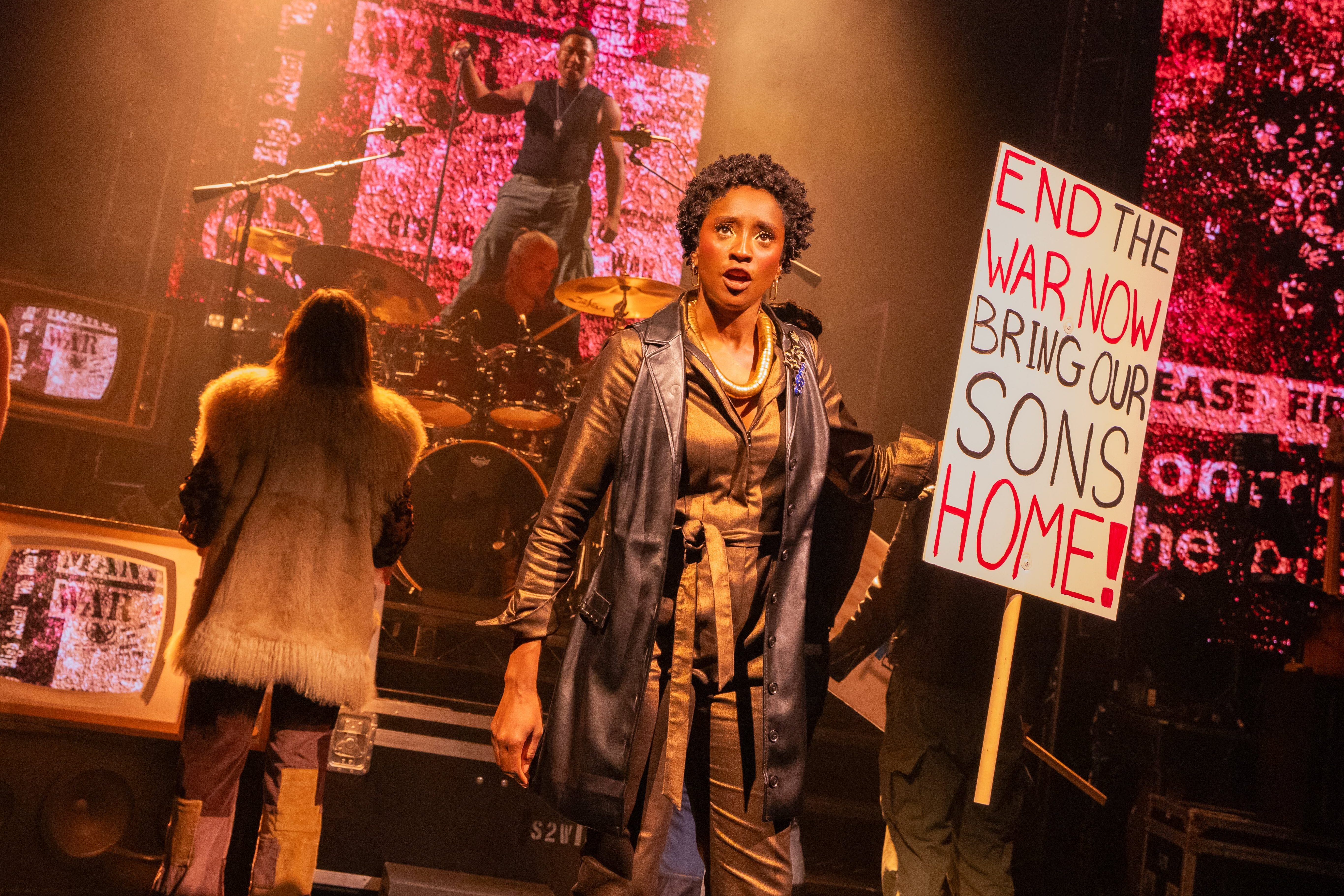

Set against this, it’s refreshing to see a mainstream movie of this size and scale that tries to be something wholly different. And some of the set-pieces — hundreds of extras dancing to Williams’s 2001 song “Rock DJ” in London’s Regent Street; a vast CGI monkey brawl at a Williams mega-gig in the early 2000s — have to be seen to be believed, ideally on a giant screen. Had it been produced at vast cost by a streaming service, nobody would have been surprised or bothered by its inability to perform theatrically — Apple, for instance, have yet to produce a picture that has made a commercial profit in cinemas — but it is hard to avoid a sense that many believed that Better Man was doomed from the outset (memories of 2019’s true dog, Cats, are still fresh) and threw it to the wolves with a half-hearted marketing campaign that never conveyed to a US market who Williams was and why audiences should care. There will never be another film like this — and there certainly won’t be any more Williams biopics — which is understandable, but in all its strange, unique glory, Better Man deserved a better shot.

Leave a Reply