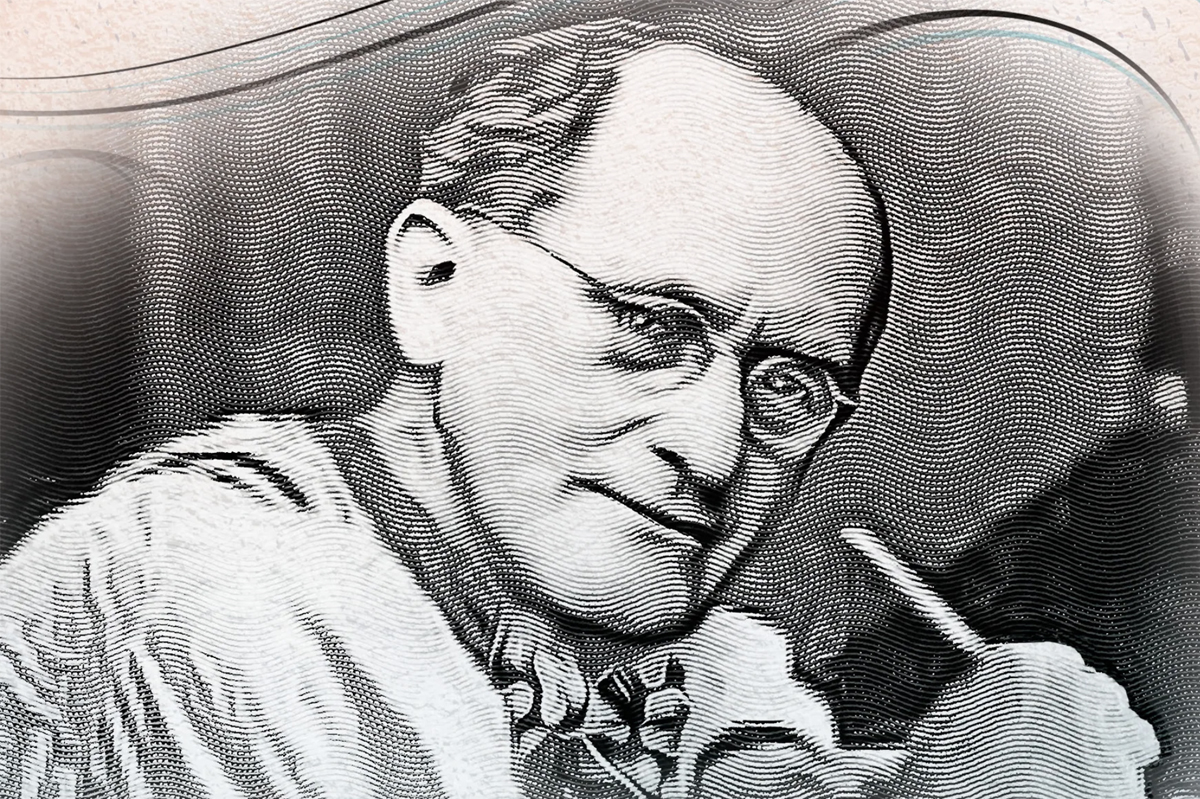

How can an artist express social and political dissent in a polarized, volatile time? Look no further than the sobering and rousing Ben Shahn: On Nonconformity.

Throughout his decades-long career, Shahn (1898-1969) crafted paintings, murals, posters, drawings, photographs and prints chronicling the news of the world, with a focus on the suffering of society’s most wounded. This is the first major retrospective of his work to appear in the US since 1976. The country has changed, and yet Shahn’s work remains as timely as ever. His social-realistic approach fell out of fashion as critics came to prefer abstract and pop art. But Shahn remained true to his own aesthetic, as the show’s 175 works demonstrate. The show’s title derives from a lecture he delivered at Harvard in the 1950s, in which he declared, “To create anything at all in any field, and especially anything of outstanding worth, requires nonconformity, or a want of satisfaction with things as they are.”

Shahn’s nonconformity bears witness to the calamitous timeline of the 20th century. His unflinching vision of a world gone awry is as powerfully direct as his late-in-life compositions of compassion and hope.

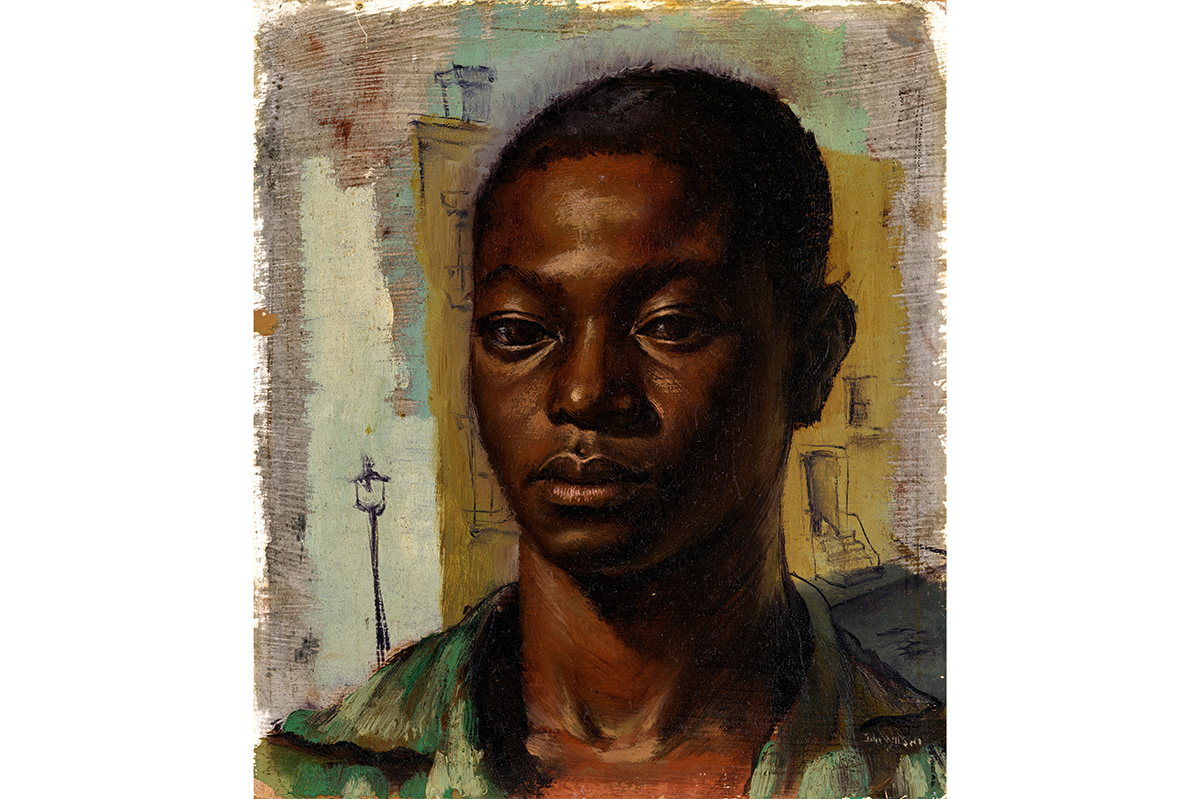

Born in Kaunas (then part of the Russian Empire, now Lithuania), he immigrated to New York with his family in 1906. His first language was Yiddish, his ethnic and religious background Jewish, his politics left-wing – an attitude perhaps ingrained in him by the Czarist government’s exiling of his father to Siberia in 1902 for suspected revolutionary activity.

Gallery by gallery, we see Shahn’s work develop and mature from the 1930s onward, starting with eight of the 23 paintings and studies that make up his monumental series “The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti” (1931-32). The controversial trial and execution of the Italian-American working-class anarchist immigrants Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti had become a left-wing cause célèbre when they were found guilty of armed robbery and murder. But the evidence was circumstantial, and riots around the world protested what many – including Shahn – viewed as a miscarriage of justice.

The first and most famous of the series casts its own verdict. On a large canvas, the gray-faced corpses of the electrocuted Sacco and Vanzetti lie in their caskets while three glowering members of the committee that condemned them loom above. As if to emphasize their hypocrisy, two of them hold white lilies, the symbol of martyrdom.

He accepted a commission from the New Deal’s Resettlement Administration to produce a work for Jersey Homesteads, a cooperative town that housed Jewish garment workers. In a 1936 study for the 45ft mural, he portrays impoverished European Jewish immigrants (like his family) arriving at Ellis Island near the turn of the 20th century. Note the coffins in the background: the dead and the history these migrants have left behind are just in the distance. At a time when Hitler was in power in Europe, and anti-immigration feeling in the US ran high, the coffins may also warn of the fate suffered by those denied entry.

Around this time, Shahn met his second wife, the activist and lithographer Bernarda Bryson, and became increasingly interested in photography. He began to capture images that he later repurposed in his other works. Many photographs document the devastation wrought by the Dust Bowl in the Midwest and Great Plains; others capture poverty-stricken areas in the South.

Making connections between these photos and Shahn’s later works provides insight into his creative process. One example: his 1936 candid of a Lower East Side kosher fish store features an eye-catching sign with a large carp – often used by Jews to make gefilte fish. Some years later, in his 1947 painting “New York,” a yellow and orange carp swims through a surreal cityscape composed of cage-like skyscrapers, a scale, and a skeletal male figure lying prone with hands clasped before him. Could these unsettling images be the disparate memories of the solemn, black-hatted man on the right side of the canvas? The man who seems to be walking right out of the painting, whose appearance suggests he is an observant Jew, perhaps even a Holocaust survivor?

While working for the Office of War Information during World War Two, Shahn was horrified by the images he saw of bombed-out villages, wasted cities, and the ghost-like people who wandered through the ruins in search of survival. In “Italian Landscape” (1943-44), women hooded in widows’ black stand amid the rubble of a church, while three men carry a plain white casket through medieval arches. The colorful bombed-out scene in “Liberation” (1945) at first seems a jolly, circus-like celebration of post-war freedom – until you notice the dead-eyed gazes of the children who seem to be swinging on rope ladders for their life amid the world’s char and rubble.

The 1950s brought the McCarthy era, Cold War anxieties, and the Atomic Age. “Second Allegory” from 1953 presents a strong anti-bomb statement, filled with Armageddon-like fire and crystalline fall-out. A giant finger (God?) in the sky presses down on a man cowering in shame and fear on the ground. His identity is open to interpretation. Perhaps it is J. Robert Oppenheimer, whom Shahn portrayed in a chilling 1954 charcoal sketch that embodied the scientist’s mournful “I am become death.”

The exhibit’s final section, titled “Spirituality and Identity,” shows Shahn coming full circle, in his last years, back to the Jewish teachings of his youth, especially biblical texts, traditions and legends. One of the most beautiful and mystical of these later works, “Where Wast Thou?” (1964), which refers to a famous passage from the Book of Job, illustrates the Jewish tradition of wrestling with God. Anchored at the bottom by gold-leaf Hebrew calligraphy, the watercolor depicts a whirling web of winds in motion amid sparkling stars. Even as all the colors of the universe seem to converge and connect in a fantastical swirl, there is no answer to the painting’s title. That is left for the viewer to ponder.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 29, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply