Ben Macintyre has a knack of distilling impeccably sourced information about clandestine operations into clear, exciting narrative prose. His latest book, about the April 1980 Iranian embassy siege in London, starts as it means to go on — with a snapshot of seven Range Rovers, two Ford Transit vans and two furniture lorries pulling out of Bradbury Lines, the then headquarters of the Special Air Service (SAS) in Hereford. Lying low inside were forty-five soldiers and “enough weaponry to fight a medium-sized war.”

Each man carried a submachine gun, mostly the “reliably lethal” Heckler & Koch MP5, which fires thirteen rounds a second, with four thirty-round magazines of 9x19mm parabellum bullets. (Macintyre helpfully provides the Latin derivation — si vis pacem, para bellum: if you seek peace, prepare for war.) Additional paraphernalia included gas launchers, stun grenades and other gizmos, with heavy kit such as scaling ladders following in the pantechnicons.

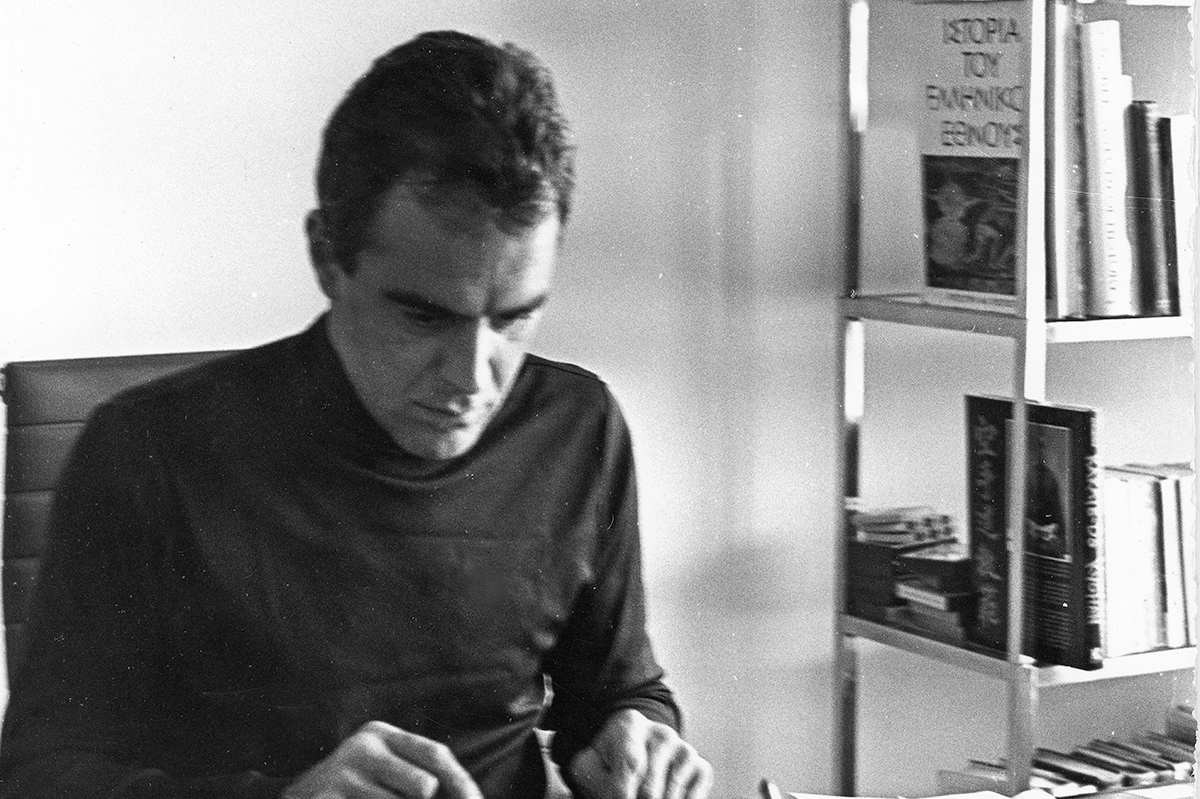

The embassy siege culminated in a maelstrom of smoke bombs, bullets and men abseiling down the building

This elite unit was bound for London, where little more than eight hours earlier six gunmen calling themselves the group of the Martyr Muhyiddin al-Nassr had stormed the Iranian embassy at 16 Princes Gate, Knightsbridge. They all came from Khuzestan, an oil-rich but otherwise peripheral Arab-speaking region in the south-west of the new Islamic Republic of Iran. They demanded the release of ninety-one Khuzestan activists who had festered in Iranian jails since Ayatollah Khomeini had taken power fifteen months earlier.

The Middle East was experiencing a period of unusual instability. The oil price rise of 1973-4 had brought vast new wealth and fueled demands for social change which often boiled over into opportunist acts of terrorism. A new breed of “guns for hire” emerged, among them the Palestinian renegade Sabri al-Banna, known as Abu Nidal. In 1973 his men had stormed the Saudi embassy in Paris, taken hostages and forced the French government to fly them to Kuwait.

Macintyre describes how Margaret Thatcher’s government, wary of London’s growing notoriety as “Beirut-on-Thames” and mindful of the Americans’ recent failure to free hostages held in their Tehran embassy, was determined not to repeat any such weakness. So, along with vivid details about the SAS deployment, he probes the closely protected heart of Whitehall, particularly the Cabinet Office Briefing Room (Cobra) — then hardly known but now synonymous with national crisis management. He highlights the politicians’ nervous maneuvering and their interactions with the police, security services and military.

The book inevitably centers on events in and around Princes Gate — from the moment PC Trevor Lock, the unsuspecting member of the Diplomatic Protection Group guarding the premises, was bundled into the building by the gun-toting Arabs. Over the next six days tensions rose and seldom fell, as three distinct groups played out their dramas both individually and collectively. The terrorists were led by Towfiq al Rashidi, a slim man in his twenties with the alias “Salim.” His team had been trained in Iraq by Abu Nidal — noticeably poorly, as the members bickered about negotiating with the outside world and about how far to carry their threat to kill the hostages.

Then there were the envoys and other embassy employees. Since Iran’s diplomatic corps had been purged after the Shah’s fall, the deputy press attaché was a paid-up Revolutionary Guard, charged simply with keeping colleagues in line. His frenzied reaction when a gunman scrawled a slogan reading “Death to Khomeini, down with the Turbaned Shah” is both comic and chilling. This male complement was enlivened by five secretaries — one a constant hysteric, another the attractive, quick-witted Roya Kaghachi.

Finally came seven visitors of other nationalities unlucky enough to be caught inside the building. Macintyre imbues them with personalities and foibles, from the jittery BBC journalist Chris Cramer, whose stomach illness permitted him an early exit, through the resourceful PC Lock, to the worldly Syrian journalist Mustapha Karkouti, who, as someone who straddled both western and Middle Eastern cultures, was able to intervene at difficult moments.

Six days of high drama culminated in Operation Nimrod, the SAS assault — a maelstrom of smoke bombs, bullets, smashed windows and grown men abseiling wildly down the building. The whole proceedings quickly became the stuff of legend. Within two years, the excruciating Lewis Collins film Who Dares Wins was released.

Was it worth it? Not for the terrorists, five of whom were killed. The fate of Khuzestan (also known as Arabistan) gained little coverage, and the region only suffered further internal repression. But the reclusive SAS emerged from the shadows as their exploits were aired on primetime television in newscasts which were the making of young journalists such as the BBC’s Kate Adie. Thatcher also received a boost. And Macintyre, who has been entertaining us for years with histories of quirky spooks, such as the boffins behind the wartime intelligence deception Operation Mincemeat, has now, with enviable contacts in the SAS, consolidated his preeminent position as an author of finely constructed non-fiction action thrillers.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.