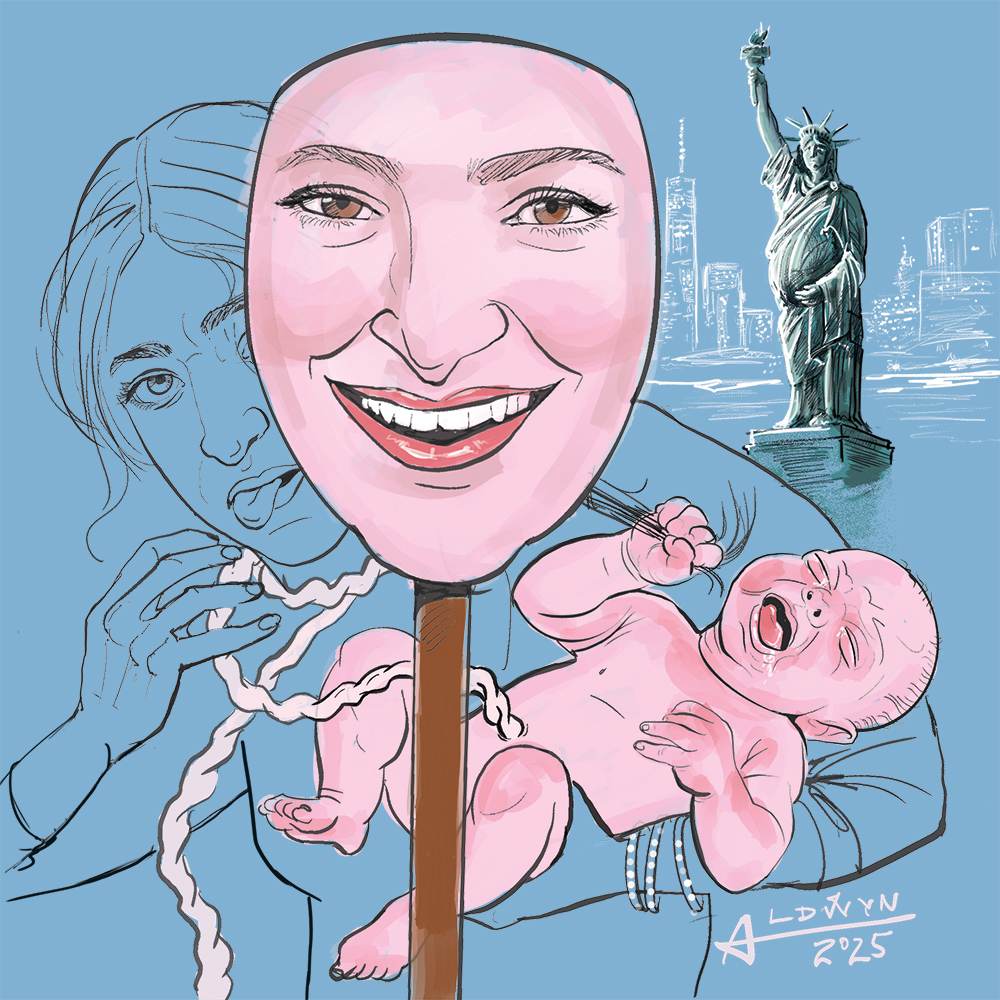

I am expecting Sarah Hoover to be brash. The New York art-scene stalwart and influencer has written a warts-and-all misery memoir about motherhood and self discovery called The Motherload, which is presently cruising atop US bestseller lists.

The book, unanimously agreed to be “unflinchingly honest” about all the bad things that can happen on a woman’s journey to and through new motherhood, opens with a stream-of-consciousness account of a party Hoover threw at the Chateau Marmont in 2017 for her first baby’s ten-month birthday. “I’d be in LA for a couple of weeks, staying at the hotel, and a diet of room service and edibles was my general game plan. Throwing a party would be the icing on that mess of a cake,” she writes, before describing the kind of nihilistic revelry that would make most new parents – those without round-the-clock childcare, that is – feel like dying before laying eyes on a single weed gummy. Subsequent chapters are called, among other things, “Mother Wound,” “First Signs,” “Off the Deep End We Go,” “Brain Explosion,” “Brain Switch” and “A is for Autonomy.”

But Hoover, 40, is not brash. In fact, she is so softly spoken that I spend most of the interview, which takes place over tea and scones at London’s Ivy Kensington, trying to hear her. And while she lives in a privileged bubble of wealth and ease – a fact that she nods to repeatedly in the book – she is also not your typical art/fashion socialite. Hoover, who married artist Tom Sachs in 2012, grew up in Indianapolis, Indiana, where she was “very serious about ballet,” taught by the same post-Iron Curtain wave of Soviet émigrés who mercilessly oversaw my violin education in Boston. She co-founded the “accelerator fund” at the American Ballet Theatre to help female choreographers get work commissioned.

‘Working full-time is incompatible with being a mother. It brings me to tears. It’s a rough lesson to learn’

Her maternal great-grandfather was a Jewish-Polish immigrant to New York. She attended NYU, studying history of art, before taking a masters in cultural theory at Columbia, interning during summers at the Met and then landing – through a stroke of luck – a job at the Gagosian gallery (“I was passing my résumé around in Chelsea [and was] in the right place at the right time”). New York had to be her final destination. One summer she saw a performance of Glass Pieces, a ballet set to music by Philip Glass, and “it changed my brain: I had never heard music like that or seen art like that. I had to go where the artists who live like that were.”

After more than a decade living large in New York, “I expected motherhood would hit me harder or differently” than it did her impeccably turned-out gallerist peers. At any rate, she felt cut off from – even bored by – the realities of her decision to get pregnant and ignored the whole thing till it was happening; no prenatal classes, no preparation. Hoover says she hoped “when I have a baby I will love it so much the maternal instinct will kick in. But it didn’t happen.”

The pregnancy with her now eight-year-old son was bad enough – she had severe morning sickness (which she had even worse with her one-year-old daughter, who was born under happier circumstances). But the birth was traumatic. Its gory terror and pain blew Hoover’s whole motherhood project dangerously off course, kicking off two years of immense suffering as she dealt with the double horror of failing to bond with her baby (she eventually did) and of being made to realise she couldn’t keep up the same pace postpartum as she had before. “Working full time is incompatible with being a mother,” she says, quietly. “It brings me to tears; it’s a rough lesson to learn.” Fathers, meanwhile, are “handled with kid gloves… men are fully capable of being equal partners, fathers and caregivers, but culture gives them a big fat pass and I think women are at the end of wanting to put up with that.”

How does Hoover connect the dots between her own experience and this most classic of feminist issues? “Tell me what feminism means,” she says urgently. “I don’t know if this is feminism. But I could not stand up for myself in a delivery room. I am 40 years old and I still find it hard to say no, lest I seem impolite. That had a real impact on the delivery. The doctor didn’t care if I was broken, really broken. The doctor had no training in how to care for a woman who has been sexually assaulted, which one in three has, and which I experienced.” Hoover has survived assault, including rape. What had she wanted out of the delivery? “I wanted to not die, and I ended that year wanting to,” says Hoover.

The first chapter of The Motherload crashes to a finish with the statement: “I’d been misled.” I am not the first reader to find herself perplexed by this, given the fashionableness of blistering, taboo-busting “honesty” about pregnancy and motherhood, in the same spirit that now extends to all other aspects of female life.

But Hoover has clearly hit a nerve: this stuff has been too literary, she believes, and has not gone far enough. “Women feel extremely dissatisfied by our culture. What it’s like to be a woman, and especially a mother: these are areas where women are feeling unseen.” Hundreds of women have come up to Hoover, she says, after book events and said she has let them say out loud the things they feel, including, sometimes, that “being a mom sucks.”

I push her on the political significance of her rough ride on the maternity train. In an age of MAGA bros and their pro-natalist adherents breeding like mad; in which Donald Trump’s fans are trying to valorize traditional motherhood while killing off abortion rights and even contraception; in which trad wives are some of the most successful female influencers on the same channels she uses. I get something of a cop-out in reply: all women should do what makes them happy. “The real win is I get to live with my truth,” she tells me. “I’m OK with the darkest things that have happened to me.”

The Motherload is no feminist treatise. But in making a rollicking tale of hedonism, psychological hijinks and gory physicality out of some very real archaisms in women’s health, it does its bit for the sisterhood.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply