Imagine Quentin Tarantino with a conscience, or even a historical consciousness. It’s easy if you try, as a rich junkie once sang, even if Tarantino never bothered to remove the quotation marks from every scene, as if life was all reference and no reality. Then imagine the film noir, that moral grisaille of the Thirties where everything comes in shades of gray, pulled into the technicolour Sixties, so that the fabrics are bright but the morals are polarised into good and evil, black and white, with darkness all around, and above us only sky.

Then watch Drew Goddard’s Bad Times at the El Royale, in which the ironies are adult like the complexities of film noir, the furnishings and mood are the nylon and Nixon of the Sixties on the turn, and the materials of Tarantino’s deadly frivolous become deadly serious. All thrillers work towards a reckoning, but this one expands into an indictment of its age. Bad Times at the El Royale is pitched as ‘neo-noir’, but it’s really neoconservative noir, showing just why the Sixties went so wrong. Drew Goddard may never work in Hollywood again.

Which would be a pity, because Bad Times at the El Royale perfectly balances its enchanting and appalling elements from the moment Darlene Sweet (Cynthia Erivo), an African American soul singer down on her luck, enters the El Royale motel as one half of an odd couple. The other half is Father Flynn, an old priest. He is played, wonderfully, by Jeff Bridges who, after The Big Lebowski, is to movies about the Sixties as Charlton Heston was to the swords and sandals epic. A third and fourth wheel arrive in the form of Laramie Seymour Sullivan (Jon Hamm), a vacuum cleaner salesman with corny patter and a checked sports jacket; and Emily Summerspring (Dakota Johnson), a rude young hippy.

There are no other guests, and only one member of staff, Miles (Lewis Pullman). The El Royale, Miles says, is a ‘bi-state establishment’; a red line running through the lobby marks the line between California and Nevada. It used to be ‘hustlin’ and bustlin’,’ Laramie Sullivan explains, pointing to the Rat Pack photos on the walls, a ‘hidey-hole for the Tahoe swells’. Dean Martin even recorded a song about it, ‘Half in Tahoe with Judy’. But then there was a problem with licensing, and no amount of pink and purple flock wallpaper could bring back the glamour.

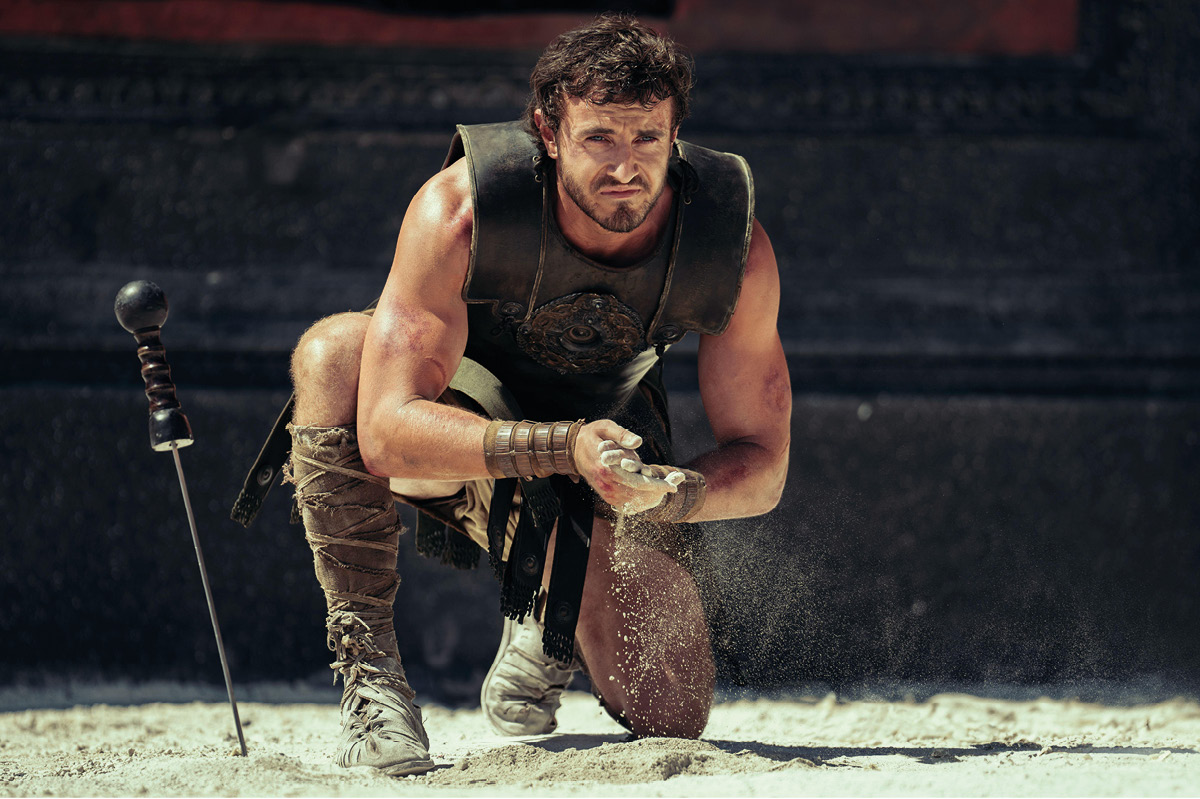

What remains is the sleaze. Something is wrong from the start. The first sequence shows a man hiding a bag of money under the floor, and then being shot by a visitor. Father Flynn isn’t a priest. He’s Dock O’Kelly, a recently paroled bank robber whose memory is failing, so he can’t remember which room the money was buried in. Laramie Sullivan is actually Dwight Broadbeck of the FBI, on the trail of a film showing a senator having sex. Miles the clerk has a needle hanging out of his arm. Emily Summerspring isn’t travelling alone, either. She has a young woman tied to a chair in her room. This is her sister Rose. Emily has sprung Rose from Billy Lee (Chris Hemsworth), the leader of a Manson Family-type cult. Rose has just murdered a Malibu pediatrician noted for his work with runaways.

Drew Goddard has adapted the set-up of Key Largo to the moral catastrophe of the Sixties. A group of strangers, trapped in an Everglades hotel by bad weather, discover their secret sharing. Instead of an Edward G. Robinson gangster, we have Billy Lee, holding women hostage in the name of love. Instead of Humphrey Bogart’s drifter, we have Jeff Bridges’ loser. And instead of Lauren Bacall’s love interest, we have Darlene Sweet, who really is a soul singer, and has been cast down on her luck by a business which produces love songs while exploiting their producers. The other love interest is the stolen bag of money, the quintessence of Sixties’ license.

Fifty years on, who thinks the Sixties were just a victim-free festival of liberation? Only aging Boomers and their grandchildren, the unemployed leftists who clog up the graduate schools because they have nothing better to do. The Sixties turned love into sex and sex into porn. The mitigating plea of the most wasted, wasteful decade since the fall of Rome is that it was also the decade of Civil Rights and sexual equality. But these movements were already under way before JFK shrugged off Martin Luther King and helped himself to the staff. As Darlene Sweet says to Billy Lee, these movements asserted themselves against the presumptions of men who thought they could take whatever they wanted in the name of liberation.

The real defense of a decade that wasted more cultural capital that any other is sonic. Bad Times at the El Royale is packed with great love songs, from the Isley Brothers to Frankie Valli & the Four Seasons. Their protestations of love and loyalty are mocked by their placement in a moral Everglades where everyone is an alligator. The trick may be as old as Tarantino, but Drew Goddard has endowed Bad Times at the El Royale with the kind of historical gravitas that Agatha Christie might have managed if she had introduced John Maynard Keynes and Mussolini’s March on Rome into a country house whodunnit. Which is a remarkable achievement for a tightly-written, well-paced thriller.

For what we see in Bad Times at the El Royale is the origins of the moral vacuum at the heart of American public life, and the polarisation that sets the moralist who can’t keep his pants up against the hedonist to whom no act is immoral except candid speech. There is no ‘bi-state’ option, because one person’s heaven is another’s hell, whether we choose to admit it or not as we hum along to John Lennon telling us that we can wish away morals and history and all the other human encumbrances. There is no Promised Land in California. There is no second America. There is only the absolutions of the fake preacher and the mingling of pain and hope in African American music — the moral grisaille at the heart of American life. Hear it and cry, see it and weep.

Dominic Green is Life & Arts Editor of Spectator USA.