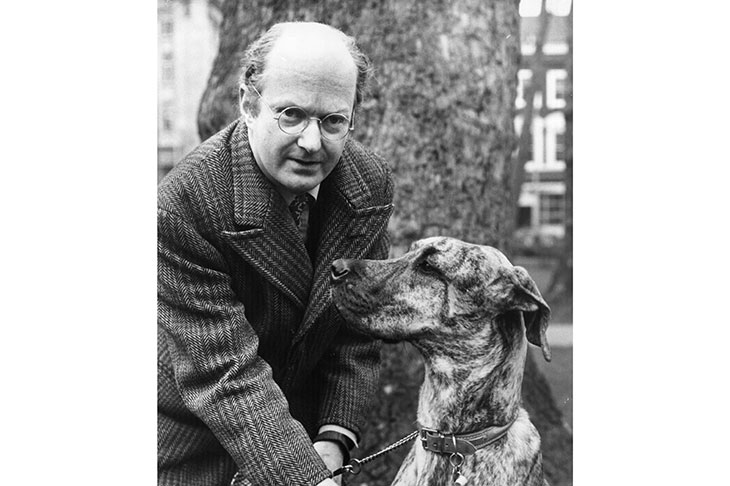

Auberon Waugh was happy to admit that most journalism is merely tomorrow’s chip paper but, of all the journalists of his generation, his penny-a-line hackery seems most likely to endure.

What made him so special? Like all great writers, it was a combination of style and substance. He had a lovely way with words — he could write a shopping list and make you want to read it — and his libertarian diatribes were wonderfully unorthodox, lambasting pompous humbugs on the left and on the right. Yes, he could be outrageous (and often gloriously rude), but even his most outlandish opinions contained a grain of truth. Above all, he was funny. His humor was absurd but it was underpinned by logic, and his savage assaults on the not-so-great and not-so-good were redeemed by some excellent jokes at his own expense.

In 2010, I compiled an anthology of Waugh’s writing (still available in some good bookshops — and quite a lot of bad ones) and was pleasantly surprised by how well it sold, and how widely it was reviewed. Sure, a lot of his fans were journalists, but his appeal extended far beyond Fleet Street. His Tory anarchism belongs to a rich literary tradition that stretches back to Swift and Dr Johnson. His death, in 2001, aged 61, was front-page news.

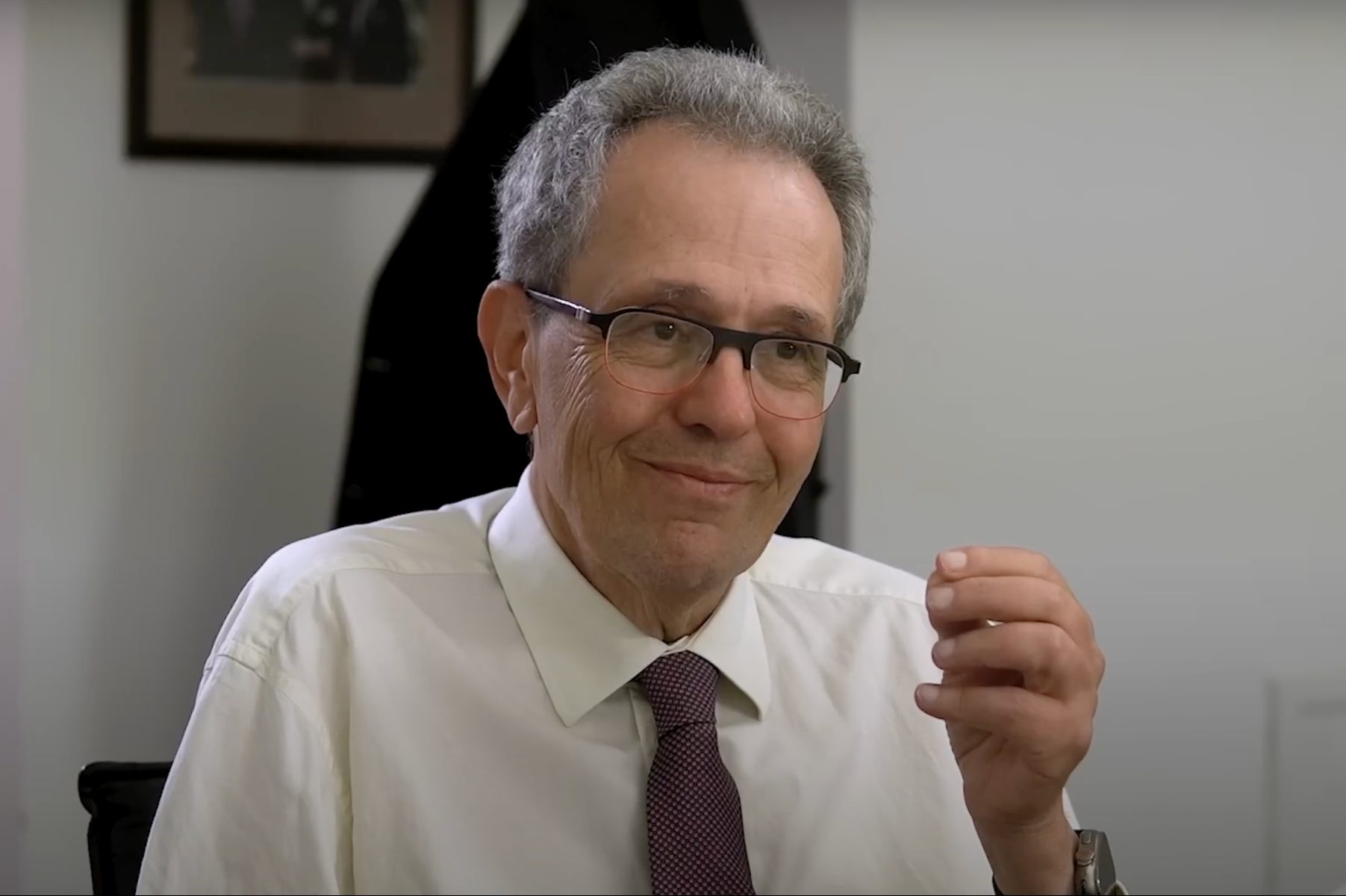

I never knew Waugh personally (I interviewed him once, which doesn’t really count, and said hello to him once or twice at Literary Review), and when I sat down to compile that anthology I was mindful thatI had no right to call him Bron, as his many friends did. Yet reading Naim Attallah’s new anthology, I wonder whether this was actually an asset. Attallah was a close friend of Waugh’s, and his boss and patron during Waugh’s long stint as editor of Literary Review. In a heartfelt foreword he calls Waugh his mentor, his hero and his idol. His affection and admiration is sincere, and often rather moving, but it doesn’t bode well for a book about a man who — in print, though not in person — could be spectacularly cruel.

Like a eulogy at a funeral, Attallah’s adulation may be touching, but it leaves the riddle of Waugh’s split personality (a demon on the page and an angel off it) tantalizingly unresolved. Attallah makes some telling points about Waugh’s ‘radical fury’, but the deepest insights in the book come from other people, most notably Kathy O’Shaughnessy, Waugh’s sometime deputy editor at Literary Review.

Attallah’s other handicap is that he’s the chairman of Quartet Books, the publisher of this Festschrift, and while A Scribbler in Soho would grace the list of any other publisher, any other publisher would surely have been more rigorous with the blue pencil. Attallah’s potted history of Soho (culled from Arthur Ransome’s Bohemia in London, which was commissioned by Waugh’s grandfather) is a diverting overture, but under any other imprint it would surely have been confined to a few paragraphs, rather than rambling on for half a chapter. Attallah also has an odd way of referring to himself in the third person, which makes him seem rather grand.

No matter. It would be very difficult to produce a bad or boring book about Auberon Waugh — and although Attallah sometimes threatens to have a jolly good go, Waugh rides to the rescue whenever the paean becomes too fulsome. Waugh was incredibly prolific (you could compile several books like this one and still not scratch the surface) and among these old favorites are many entertaining articles I’ve never seen before.

Even so, it’s an odd selection. There’s a good deal from his Private Eye diary (which he regarded, rightly, as his masterpiece) but very little from The Spectator, where he wrote a column for 20 years. There’s plenty from Literary Review but nothing from the Oldie. There’s some intriguing background about his various libel cases (‘There is nothing so funny as a person demanding money to which he is not entitled in recompense for an injury to his reputation which he has not sustained’) but nothing from the New Statesman, Books & Bookmen or his Way of the World column in the Daily Telegraph.

Anyone expecting a greatest hits may feel a bit shortchanged, but for Waugh obsessives like me (and thousands like me) this is a welcome addition to the canon. All that’s missing now is a proper biography. Maybe the chairman of Quartet Books could be persuaded to commission one. In the meantime, Waugh’s advice to Henry Porter still stands as a decent mantra for any jobbing journalist who shares his fearless desire to speak truth to power (yet avoid a writ for libel): ‘You should tell the truth as often as you can, but in such a way as people don’t believe you or think that you’re being funny.’ And no journalist was ever quite so funny as Auberon Waugh.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.