Great novelists come in all shapes and sizes, but one thing they all share is a status of half-belonging. If they had no foot in the world at all, they could hardly understand it; if they completely belonged, they could hardly understand what was distinctive. One of the pleasures of this excellent biography is fully appreciating the peculiar, liminal, not-quite-successful position Powell wrote from, and described with great exactness. In half a dozen social and professional milieux, he was a tolerated, perhaps useful minor presence, like a spare man at dinner. From the standpoint of a rather failed editor, screenwriter, soldier, socialite, he stood by and watched the world. In each case, one suspects, the subjects hardly realized they were being observed.

This is the fourth major biography by Hilary Spurling, after her full-scale lives of Ivy Compton-Burnett, Paul Scott and Henri Matisse. It is the first, perhaps, with no major surprise to spring on the reader. (What the great Compton-Burnett biography had to reveal came as news to people who had known the novelist for many decades.) Powell told his own story twice, in his novel sequence A Dance to the Music of Time, published from 1951 to 1975, and four volumes of richly enjoyable memoirs, published between 1976 and 1982. There is a gentlemanly reticence about private matters in both novel and memoir — the sentence in which Nick Jenkins, the narrator of the novel, informs the reader that he has married Isobel Tolland is, to fashionable sensibilities, indecently clipped. Nevertheless, what we have in both is a detailed and largely truthful account of events. Powell made sure there would not be much for a biographer to discover.

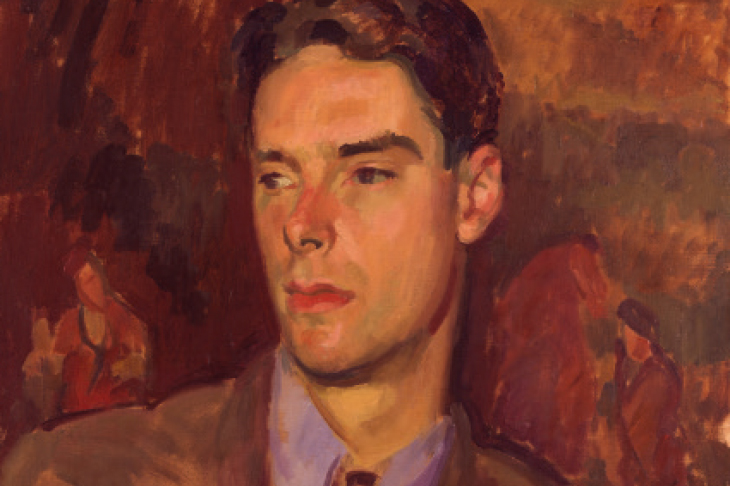

Powell came from a line of soldier gentry. The unusual fact of his childhood is that his mother was very much older than his father, and they moved around various London addresses when he was a small child. (When, much later, he moved to a house in the country, he found the sight of fields and woods from his study window disturbing.) At Eton he made friends with Henry Yorke, later the novelist Henry Green, but otherwise did not shine at sport or intellectual pursuits. After Oxford, he took a job at a dim publisher called Duckworths and went to smart parties; he was not much of a success. ‘Ah, you’re buying experience, young man,’ a hostess remarked with evident relief at having placed him. The women of his generation made it disarmingly frank that a boy with a very moderate salary and without real prospects was of no interest to them. He made his way slowly — evidently agreeable company, he befriended the Sitwells, had an affair with Nina Hamnett, and maintained friendships with Evelyn Waugh and Constant Lambert.

The five novels he wrote in the 1930s fell under the shadow of Waugh and even of Henry Green; they are extraordinarily dry, and met with only very moderate success, though their brilliance has never been in doubt. The last of them, indeed, was published days before the war broke out and was a minor casualty of the conflict. Powell had a mixed war, though relations between him and the army never broke down as spectacularly as they did in the case of Evelyn Waugh — in person, he was always much more emollient, though perhaps not very competent. He was personally selected by a former flatmate of his friend Alick Dru, Lt-Col Denis Capel-Dunn, secretary to the Joint Intelligence Committee, to act as his sole assistant. Powell lasted nine weeks working for this ‘squat figure in a sodden British Warm… famed for his forcefulness with subordinates… manipulation of equals and ingratiation of superiors, particularly those of ministerial rank’. By the time Capel-Dunn sacked Powell, refusing a request to stay on long enough to be promoted to major (‘My nerves wouldn’t stand it,’ Capel-Dunn said), Powell had taken the opportunity to observe a singular type at close quarters. When the long novelistic silence between What’s Become of Waring (1939) ended with the first volume of Dance, A Question of Upbringing (1951), Powell’s thoughts had cohered into one of the great fascinating monsters of fiction. Kenneth Widmerpool had a number of originals, but the main one was Capel-Dunn.

Powell’s long and happy marriage to Lady Violet Pakenham connected him to generations of powerful and compelling people within one family, including the painter Henry Lamb, Lord Longford, Lady Antonia Fraser, Harold Pinter, Ferdinand Mount and Harriet Harman. In Dance, the authority and sympathy within any number of social settings is never likely to be equalled — Proust doesn’t come anywhere near Powell’s social range. Even in worlds he knew nothing about, such as music (Hugh Moreland’s symphony comes and goes with the minimum of comment), the authenticity of Powell’s portrayal of the manners of Mrs Maclintick and the music critics is deeply impressive.

The sequence has a peculiar and compelling technique; the narrator analyses rather than mulls, always looking outwards, and the appearance of things is so searchingly pulled apart that it takes on real profundity. In the great scenes in Powell, the characters often know much more than the narrator admits, or will share with the reader. ‘So often one thinks,’ Powell writes, ‘that individuals and situations cannot be so extraordinary as they seem from outside: only to find that the truth is a thousand times odder.’ When Jenkins and Jean play at not knowing each other at the memorial service in The Military Philosophers (‘[Madame Flores] spoke English as well as her husband, the accent even less perceptible’) there is a sense of struggling to make sense of surfaces. Many of the great scenes are like this: Pamela Widmerpool confronting Polly Duport at the end of Temporary Kings, or Barbara Goring pouring sugar over Widmerpool’s head. As in life, we see only the final, physical result of an internal process, and try to understand. We are not given the slack novelist’s privilege of reading many minds, and the texture is extraordinarily like life. The quality of characters dropping in and out has always been admired as resembling the process of living; less remarked upon is the constant texture of trying to read events and people from their actions and appearance, which after all is the way we all live.

Will it last? Magnificent and accomplished as it is, Dance is certainly a challenge to many readers now. Powell’s dedication to the exact period detail is unmatched — the titles of the books his characters write, for instance, inspire awe in their precise plausibility, from St John Clarke’s Fields of Amaranth to J.G. Quiggin’s Unburnt Boats to X. Trapnel’s Dogs Have No Uncles to Ada Leintwardine’s gritty I Stopped at a Chemist (‘a tolerable film as Sally Goes Shopping’). The dedication goes as far as making sure the characters’ anecdotes have the right degree of dullness. ‘The King is supposed to have said “Well, Vowchurch, I hear you are marrying your eldest daughter to one of my generals,” and Bertha’s father is said to have replied, “By Gad, I am, sir, and I trust he’ll teach the girl to lead out trumps, for they’ll have little enough to live on.” Edward VII was rather an erratic bridge-player, you know.’ Notoriously, Powell’s dry wit hardly travelled. Even now, I’m sometimes not quite sure if he is joking — when, for instance, his narrator remarks: ‘I was then at the time of life when one has written a couple of novels…’ Will readers in the future be able to catch his complex tone at all?

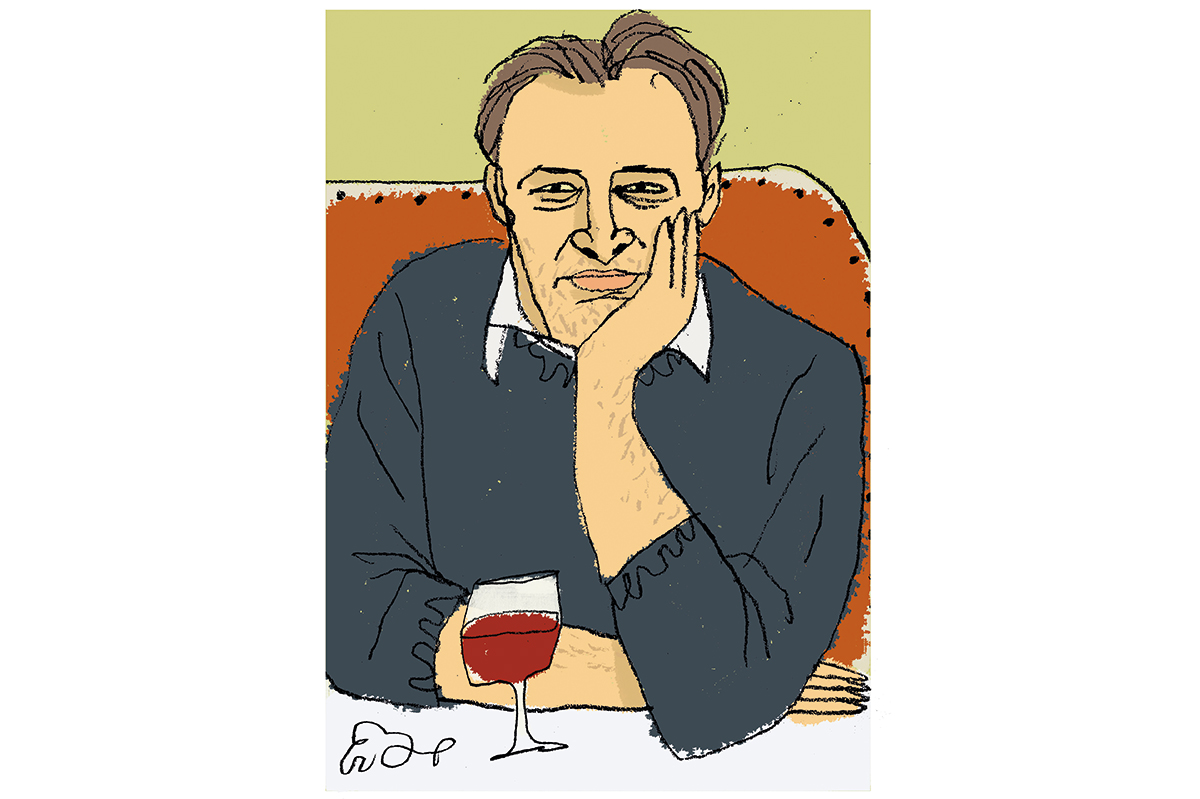

This is a fine biography by a writer who knew Powell well, and who understands how writers think, and how novelists stand in relation to their material. Much of Dance is roman-à-clef if anything ever was, but Spur-ling takes the trouble to give Julian Maclaren-Ross and Constant Lambert lives quite separate from X. Trapnel and Hugh Moreland. Three quarters of the book is taken up by Powell’s life before Dance started to be published, and his last 20 years, after it came to an end, are wrapped up in a mere 14 pages, largely of Spurling’s own memories of Powell. This I think regrettable: the four volumes of memoirs are barely mentioned. Since such important events as the famous 1982 dinner for Mrs Thatcher, hosted by Hugh Thomas with Philip Larkin, V.S. Pritchett, Tom Stoppard and Mario Vargas Llosa as Powell’s fellow guests don’t feature, I think there must be much more to say about Powell’s last years than this suggests.

Nevertheless, in this biography Powell gets what he deserves — a biographer of wide sympathy and human understanding, in tune with a style of manners and a way of thinking that is slowly vanishing, and very unlikely to be resurrected. Beneath that conventional exterior, the Regency house in the country and the portraits of what was coming to be called the Establishment, Powell was a writer as self-doubting and as shockingly original as Beckett. It’s good to have a commentator who understands that.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.