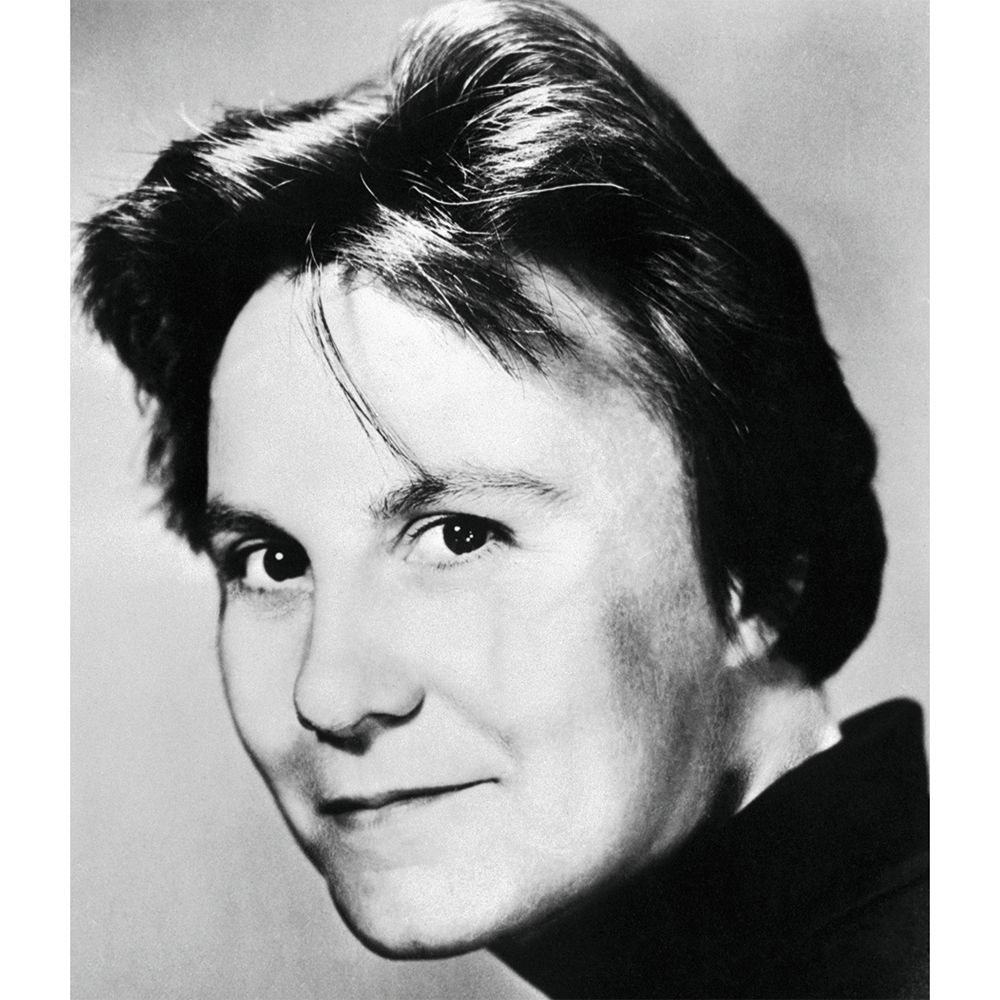

Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird hardly needs an introduction, as I expect everyone in the world has read it, or has seen the film starring Gregory Peck. (If you haven’t read it, perhaps you should.) Lee, incidentally, went to visit the film set, and had this to say about Peck: “an inspired performance. In some mysterious way, Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch transcended illusion.” If that seems a tad clichéd and not especially insightful, then I’m afraid to say that this is the general tenor of the nonfiction pieces in The Land of Sweet Forever, alongside eight previously unseen short stories.

Go Set a Watchman, a novel which was largely viewed as To Kill a Mockingbird in embryo, appeared ten years ago, to not much acclaim. These short stories were all drafted in the ten years before the publication of Lee’s massively successful novel about race and justice in small-town Alabama, (based on Monroeville, where Lee grew up). The fictions here mostly circle around the same subject matter and are nearly all set in what is essentially her hometown, containing characters that cycle through versions of people she knew, including her barely disguised family and friends.

There is a richness to the Southern-set narratives: a deeply felt sense of place, a gift for character, a fine morality. “The Water Tank” sees Abbie, a “town girl” who likes to hang out with the uncultured “country kids,” believing that she’s going to have a baby because a boy hugged her “with his pants unbuttoned.” Lee is excellent at capturing the intensity of early adolescence. The story, though it veers toward melodrama, is saved by a satisfyingly inconclusive ending. In “The Binoculars,” a little girl fantasizes about being taught by her brother’s teachers; to her disappointment, on her first day at school, Miss Turnipseed, a new teacher, instead swiftly berates her for being able to read. (This snippet found its way, altered, into To Kill a Mockingbird.)

One of the more successful stories, “The Pinking Shears,” contains a version of Mockingbird’s Scout Finch in Jean Louie, a sparky youngster who cuts the long hair of a preacher’s daughter against her father’s wishes. There are many memorable images that come from the story, with the preacher and his nine dirty children evocatively portrayed, his wife a “tub of a woman.”

In “The Cat’s Meow,” the narrator, again a version of Lee, returns home for Christmas to visit her sister, Doe (based on Lee’s older sister). Here Lee tries to tackle racism; the story features a black gardener called Arthur. Well-educated and hard-working, he turns out to be on parole, having been arrested for a minor misdemeanor and given a 20-year sentence. This fact confirms all the worst prejudices of Doe, a segregationist. The narrator, however, simply keeps silent, browbeaten by her sister. It shows how endemic those attitudes were in the South and raises the question of complicity by silence.

Less successful, though, are the New York-set stories. It’s often forgotten that Lee lived in the city (and what’s more, was friends with Truman Capote, who grew up next door to her in Alabama.) In “A Roomful of Kibble,’ Lee strains for a sophomoric, J.D. Salinger-esque vibe: “My friend Sarah Mitchell is having a hard time living with herself these days, and I shouldn’t wonder, after what she did.” While it contains some good lines (Sarah’s prissy mother manages to “convey the impression that even the time of day was improper”), it is unsure of itself, ending with a sudden disaster which does little to throw light on the rest of the story. “This is Show Business” contains a faintly amusing account of the narrator trying to drive an automatic car, but otherwise falters.

The nonfiction pieces, all published previously, throw up some arresting sentences, such as this, from a letter to Oprah Winfrey’s magazine: “And, Oprah, can you imagine curling up in bed to read a computer? Weeping for Anna Karenina and being terrified by Hannibal Lecter, entering the heart of darkness with Mistah Kurtz, having Holden Caulfield ring you up – some things should happen on soft pages, not cold metal.” There’s a fierce passion there – and a poetic ear, too.

But mainly the essays hum with platitudes: “Without love, life is pointless and dangerous.” Lee even, like any rookie writer, begins “The Land of Sweet Forever” with a clumsy reworking of Austen’s famous line: “It is a truth generally acknowledged by the citizens of Maycombe, Alabama, that a single woman in possession of little else but a good knowledge of English social history must be in want of someone to talk to.” There is, too, should you wish to try making it, a recipe for “crackling bread,” first printed in the Artists’ and Writers’ Cookbook. You’ll need a pig.

Lee was insanely lucky: some friends paid her an income for a year so she could write. This luxury is documented in “Christmas for Me,” one of the nonfiction pieces. Here, she states how hard it was to find her voice. The fiction shows a writer trying her darndest to find that voice. Whether we need to see the inner workings of that process is another question.

While the critical reputation of To Kill a Mockingbird continues to be assailed – with Lee herself accused of racism and the novel of sugarcoating the South – it’s undeniable that the novel holds an important place in the annals of American literature and the nation’s construction of itself. Justice, decency, honor: in the pieces collected here, we can see Lee striving to work through these ideals. The stories show a hard-working writer looking for accomplishment and will please fans and Lee scholars alike. In the end, though, they remain offcuts, while Mockingbird will always find its readers.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply