Feminism? Pfft! Marianne Faithfull practically spat the word at me when I interviewed her in 2017. Then she rowed back, conceding that she’d spent most of her life “standing up for women’s rights… I’ve had to.”

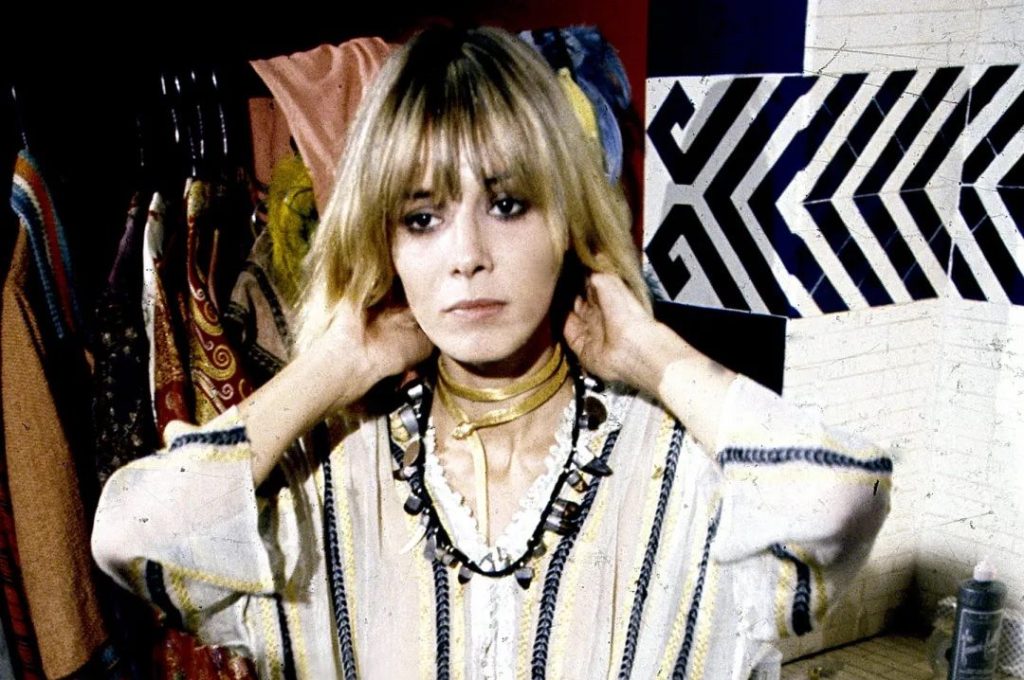

In chronic pain with arthritis, she’d struggled into a comfy chair while directing me to squat on the mucky floor at her feet. Who could blame her? From the moment the record producer and impresario Andrew Loog Oldham first packaged her as a teenage “angel with big tits,” the media had refused to treat her with respect. She’d been sold first as a virgin, then as a whore — the posh convent girl corrupted by Mick Jagger, found wrapped in only a rug at the Redlands drug bust. While the Stones’ wild behavior saw them celebrated as rock ’n’ roll pirates, their women’s ambitions and reputations were tossed overboard.

That sexist narrative is crisply corrected in Elizabeth Winder’s deliciously gossipy Parachute Women. It tells the story of the four clever, charismatic women who, between 1965 and 1972, helped forge the sound and style of the macho Rolling Stones: Marianne Faithfull, Marsha Hunt, Bianca Pérez-Mora Macías and Anita Pallenberg. Winder, an American poet, has also written books about Marilyn Monroe and Sylvia Plath, so she’s got form when it comes to restoring complex humanity to twentieth century muses. But she writes more as swooning fan than scholar, her prose prostrate at Pallenberg’s gladiator-sandaled feet from the off.

The twenty-three-year-old Pallenberg first met the Stones backstage in Berlin in 1965. Winder invites us to picture the “Teutonic goddess” leaning against the spotty lads’ dressing room door, “her smile cocky, revealing flashes of fanglike teeth.” She dug into her pocket for a vial of amyl nitrate, then asked: “Vant to smoke a joint?” The Stones had never taken drugs before. Nor had they met a woman as intimidatingly experienced as Pallenberg. Winder notes they were used to “Carnaby Street’s trendy dolly birds with their knee socks and baby-doll dresses.” But Pallenberg had grown up “skipping school with the street kids and artists in Rome, grave-digging, beach drinking, boyfriends with Vespas, Caffè Rosati with Federico Fellini and living in Warhol’s Manhattan as a Factory girl.”

Faithfull has always credited Pallenberg with creating the Stones. She brought them swashbuckling, gender-bending flair and the cosmopolitan confidence to flout the rules. She zipped them into skirts, slipped them drugs and took them to galleries. Winder calls her a “pythoness” — a satanic majesty who humiliated, seduced, empowered, educated, bonded and divided the band as the whim took her. She goaded them into the swagger they carried into their music and they remixed tracks on her instructions.

But they all struggled with her freewheeling power. Brian Jones eventually responded by blacking her eyes and ripping up the film scripts she was offered. Keith Richards initially loved her from afar, while the competitive Jagger was irked that she out-cooled his own girlfriend, the Buckinghamshire farm-raised model Chrissie Shrimpton (whom he controlled with strict curfews and gifts of children’s toys). Jagger withdrew his offer of marriage to Shrimpton and upgraded to the more intellectual Faithfull.

Winder offers an insightful chronicle of the incestuous mess that followed: Richards getting together with Pallenberg; Pallenberg cheating with Jagger; stately homes turned into grimy, gothic theater-set opium dens with their chatelaines at first enjoying the sexy high jinks before sinking into druggy domestic drudgery; Richards spending days playing guitar on the lavatory while Pallenberg fretted over grocery orders for all his hangers-on. He offered her money to turn down film roles.

Meanwhile, Faithfull (who claims to have spent the best night of her life with Richards) suffered a miscarriage and attempted suicide — her troubles soap-operafied by the tabloids. She wasn’t given credit for co-writing the song “Sister Morphine” until the 1990s. But the albums she’s been making in her seventies outshine anything the Stones have written in decades. Her brilliant 2018 Negative Capability finds her paying blunt sisterly tribute to Pallenberg (who died of cancer in 2017). “I do understand why you want no more treatment,” she sang, “but please stay a while with those who love you, my little rebel.”

Such deep, knowing affection is a world away from the ongoing bitching between the Stones themselves, with Richards continuing to snigger about Jagger’s “tiny todger” in his 2010 memoir. But Winder doesn’t pretend that the WAGs all supported each-other. Pallenberg was ruthless in her attempts to chase Bianca Macías from the scene (eventually resorting to voodoo). Meanwhile, the feminist Macías didn’t encourage Jagger to support his daughter by Marsha Hunt. It was about Hunt that he wrote “Brown Sugar” (removed from the band’s touring set list in 2021). The Berkeley-educated, actor-turned-author emerges as perhaps the most enviable (because most independent and happiest) of the women in the book. Hunt never took drugs, and wasn’t that interested in the “bad lads” or their band.

As a reader you’re swayed between boggling at the outlaw glamor and eye-rolling at the drama and double standards. The women certainly emerge as more original and dynamic personalities than Mick ’n’ Keef. So it’s frustrating to read of their slide into addiction and the sidelines as their exes rolled off to stadium tours in corporate limos. You’re left wondering what albums these women might have made during that period, had any label given them the same license as the lads. Had the world not insisted they remain under the thumb.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.