During the great financial panic of 1907, the banker J.P. Morgan locked the titans of the financial world in his lavish private study to determine which banks to rescue and which to let fail. This intervention saved the banking system, restoring public confidence. But trust in Wall Street was shaken to its core. Six years later, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act, which sought to stabilize the American financial system by establishing a central bank to regulate credit and serve as lender of last resort. By the mid-1920s, the very mechanisms that were designed to promote stability had fueled a surge in stock market speculation. In 1929, a narrative history of this feverish bull market and its tragic unraveling, Andrew Ross Sorkin seeks to illuminate “the most significant – and largely misunderstood – financial disaster in modern history.”

Throughout the 1920s, National City Bank and its securities affiliate, the National City Company, had extended credit to investors and brokerage firms, allowing stocks to be purchased with as little as 10 percent deposit. Margin loans increased sixfold over the decade. Once confined to professional investors, stock speculation became a national pastime as Americans borrowed their way into the booming market. At the start of the year, the surging “Coolidge market” had begun to resemble a bubble. As Sorkin writes: “On February 2, the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, fearing that a speculative bubble was taking hold, issued an advisory to the Fed’s regional banks, discouraging them from making loans to support stock speculation, particularly stock that was bought on margin.”

In an attempt to cool this market, the New York Fed had moved to raise the discount rate from 5 to 6 percent. “The Fed’s killing the goose which laid the golden egg,” complained Charles Mitchell, National City Bank’s president and chairman. To persuade the president-elect, Herbert Hoover, to take his side against the Fed, Mitchell called upon the influential auto magnate William Durant. “I’m sure there’s a way we can get to Hoover,” Durant reassured him.

Sorkin is at his best in his granular reconstruction of the unfolding collapse on Wall Street. He traces the months of 1929 week by week, from the Federal Reserve’s warnings about speculative lending in February to the cynical maneuvering of bankers and industrialists attempting to prop up the market. On March 26, defying the Fed’s tightening policy, Mitchell ordered his bank to extend loans, “no questions asked,” to support share prices. On another fateful evening, Durant, unvetted and uninvited, talked his way into the White House to privately urge Hoover to contravene the Fed.

Sorkin’s 1929 reveals a gallery of tragic figures whose genius and folly shaped the destiny of the United States at a critical point in its history. There is Thomas W. Lamont, the impoverished minister’s son turned JP Morgan partner and de facto chairman of the bank; Jesse Livermore, the self-educated speculator who got his start running bets for organized crime in Boston before making millions as a short-seller; Carter Glass, a son of the Confederate South who overcame his lack of formal education to become the leading congressional expert on banking and a driving force behind financial regulation; and National City Bank’s Mitchell – or “Sunshine Charlie” – whose boundless optimism disguised his fatal hubris.

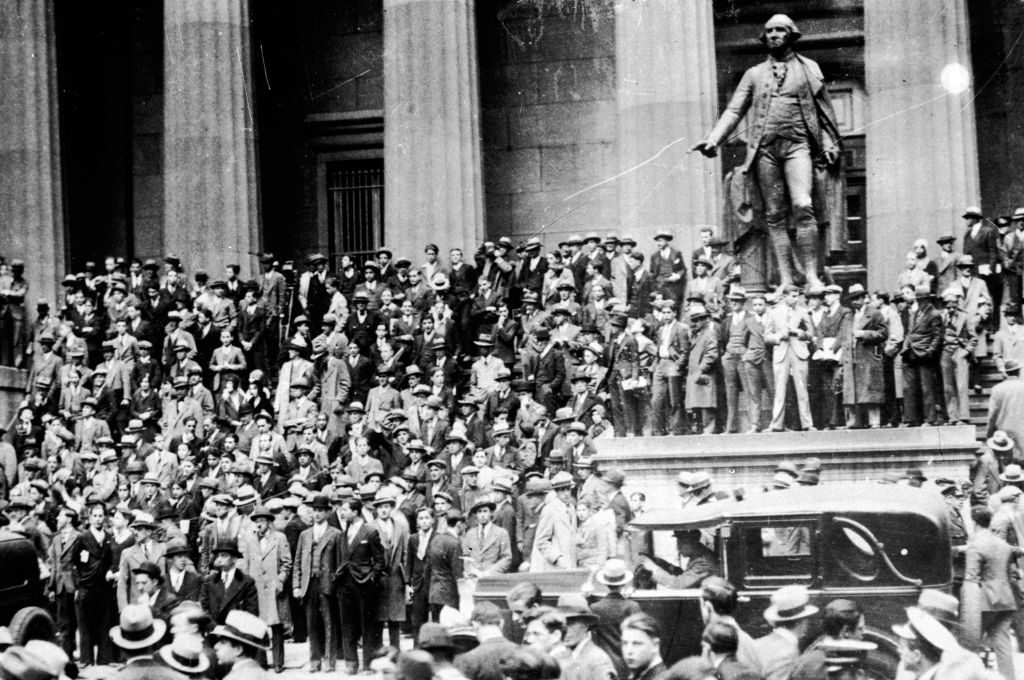

On Thursday, October 24, as the bubble began to burst, Mitchell emerged from meetings with a consortium of bankers at the JP Morgan offices in Lower Manhattan. “I am still of the opinion,” he told the press, “that this reaction has badly overrun itself.” The “Big Six” bankers had formed a pool, injecting around $100 million into the market that afternoon. All of this was coordinated in secrecy. “If the public knew exactly what they were doing, it wasn’t clear whether it would instill confidence or undermine it,” Sorkin writes. It was to no avail. When the market opened the following Monday, October 28, the Dow suffered the largest single-day drop in stock market history. The rout continued into November. “In the space of just two months, the market had fallen by half, wiping out $50 billion, which represented about half the US gross national product.”

The market rallied into the spring of 1930, recovering almost half of its losses. But then “the air simply leaked out of the balloon.” Credit markets had been eviscerated. On June 17, Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Bill, raising tariffs on foreign goods to an average of 60 percent, which worsened an already teetering economy. Then began a string of bank failures.

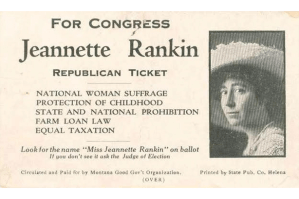

Critical accounts of Wall Street, far removed from the hagiographic magazine profiles of the previous decade, began emerging en masse in the media. Meanwhile, Hoover made himself easy prey for the Democrats, who swept the 1930 midterms, a prelude to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s landslide victory in the 1932 presidential election. What began as a vote of confidence in the American system would ultimately empower Roosevelt to reshape it entirely.

1929 revives a decisive episode in financial history amid renewed uncertainty about the resilience of American markets and the global economy. Based on eight years of exhaustive archival research, Sorkin’s study offers a rare combination of scholarly rigor and narrative verve. Implicit in his account is a cautionary insight: the very ambition driving America’s financial system ensures its perpetual vulnerability to excess and collapse.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 24, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply