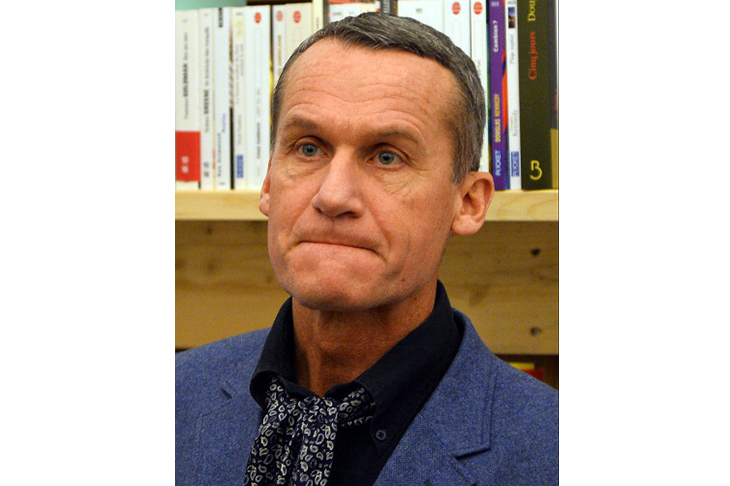

The Siberian-born novelist Andreï Makine has, as we say in the book world, a shedload of French literary bling. He’s the only writer to win the Prix Goncourt and the Prix Médicis for a single novel (Le Testament Français) which is, in pop cultural terms, like winning The Great British Baking Show and Dancing with the Stars on the same day. So one imagines that when old Andreï sat down to write this one, he enjoined himself not to cock it up.

Reader, he hasn’t. One hesitates to use the word ‘masterful’, but for The Archipelago of Another Life it feels warranted. Set largely in 1950s USSR, Makine’s novel tells the story of Pavel Gartsev, a reluctant Red Army reservist tasked with hunting down an escaped convict in the Siberian forests. With him are a cross-section of the regime: Luskas, a vicious communist apparatchik; Ratinsky, a dangerous young officer; Butov, a Falstaffian major, notionally in charge; and Vassin, a decent sergeant, weary from a life of tragedy.

This manhunt is a self-described Western, and there are structural elements of the genre: a posse of misfits, a mysterious outlaw, a high-pressure pursuit — even moonshine by campfires and a dead gold prospector. But to reduce the novel to a Western is like describing Heart of Darkness as ‘a jaunt upriver to find a chap who’s had a bit of a nervy b’.

Instead, set against the horrors of Stalin’s Soviet Union, the novel speaks more universally of human experience, of the individual’s ‘impulse for freedom’. As the soldiers venture into ‘beautiful virgin forest, crossing streams where the water was as cool as sorbet’, they become less interested in capturing the prisoner and begin to feel liberated, if temporarily, from the totalitarian regime.

Among the ‘slow, green, swaying rhythm’ of the trees, Pavel and his comrades go through a spiritual journey of sorts. From cogs in a bureaucracy, they become rehumanized, finding empathy for their quarry. But as they venture deeper into the taiga, they devolve into beastlike brutality. Pavel, though, continues through this depravity to a cleaner sort of animality, rebelling against all human society — the ‘farcical human charade’ focused on ‘desire’ and ‘conquest’ — to embrace the wild and find in the forest a richer definition of what it is to live.

Makine — in this stellar translation from the French by Geoffrey Strachan — is capable of soaring lyricism: ‘All around me the water was still repeating its melody, and the sun’s radiance fractured into glittering scales before settling into a steady flow of sombre gold at a bend in the river.’ But his prose is most impressive for its elegant authority. That, together with a narrative structured as a tale told by firelight to a listening narrator, feels like a conscious nod to the 19th century. Makine has been justly compared with Tolstoy, but here I think the better reference is Joseph Conrad. And when critics are quibbling over which great novelist your work stands beside, you can chalk that up as a good year’s work.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.