“Gliff” is a word which can mean “a short moment,” “a wallop,” and “a post-ejaculatory sex act;” to “dispel snow,” “to frighten,” and to “escape something quickly.” It’s “really excitingly polysemous,” says one of Ali Smith’s characters. It’s certainly an apt title for a book which can’t seem to define itself.

At its center are two children, Briar and Rose, who have been abandoned. Their mother is absent, caring for a sick sister, and their other responsible adult leaves to find her. The children exist in a stock dystopian world (people are surveilled by CCTV cameras and zombified by screens) with a twist: they repeatedly wake up to find that a red line has been painted around their house or camper van. They are on a list of “Unverifiables.”

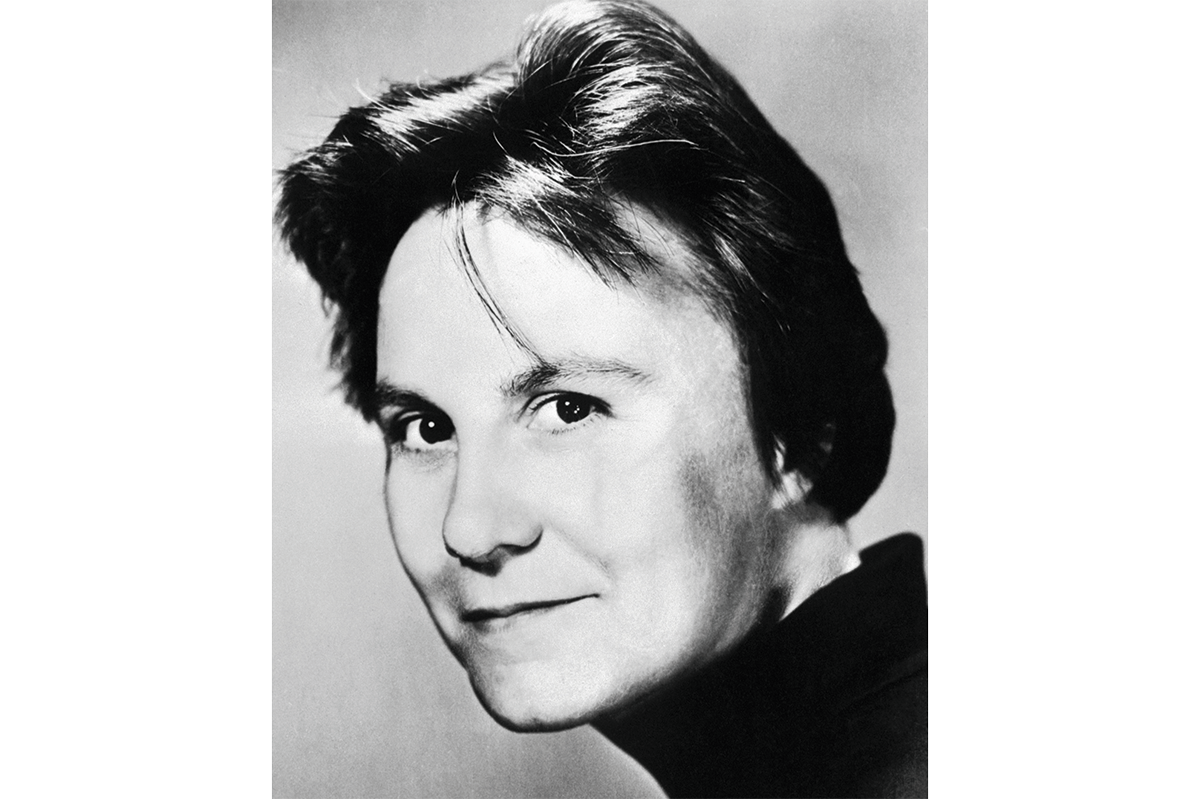

Smith’s most recent work, the Seasonal Quartet and its Companion Piece, made a novelty of responding to real-life events, such as Brexit and Covid lockdowns, in real time. Gliff is a different sort of project, but still one which reveals a desire to comment on contemporary culture. The novel is set in the not-so-distant future — a world of AI and mass technology, in ecological crisis, but with an authoritarian regime that “re-educates” recalcitrant citizens.

There’s the whisper of a good story here — about two children resisting “progress,” and about the power of language and storytelling. In the later parts of the book, swathes of narrative are rendered in dreamlike fairytale sequences. But there are many infelicities. Some of Smith’s ways of signaling her dystopian future read like details in a young-adult sci-fi novel. The children find themselves among a bunch of rag-tag misfits. People wear “educators” on their wrists and say goodbye to each other at “docking stations.”

Other problems are more serious. The novel skips over years at pace — “I’ve spent the last five years of my life not letting myself think any of this” — and leaves the gaps unexplained. There’s much to like about Smith’s impressionistic style: she wonderfully conveys the children’s perspective, and her characteristic linguistic experimentation is on full display. But the holes feel fundamental. The threat the government poses is lazily gestured at, and the possibility of resistance seems like an afterthought. The book’s emotional pull — a redemption story, of sorts — is never fully realized.

It’s difficult to judge Gliff on its own; a companion novel, Glyph, is due next year. But if this half is anything to go by, Smith’s latest project of fictionalizing the contemporary world falls flat.

Leave a Reply