We meet at Adam McEwen’s apartment on the Upper East Side, a few hours before he makes a lightning trip back to London, where he was once a journalist working for the Daily Telegraph. After studying art, McEwen worked for a while writing obituaries, and his eureka moment came in 2000 with the decision to turn his day job into art. He began to write fake obituaries for living subjects, adopting the detached prose and visual design of a broadsheet newspaper. Each text was presented as a black-and-white C-print, and subjects included Jeff Koons, Marilyn Chambers, Macaulay Culkin and Nicole Kidman.

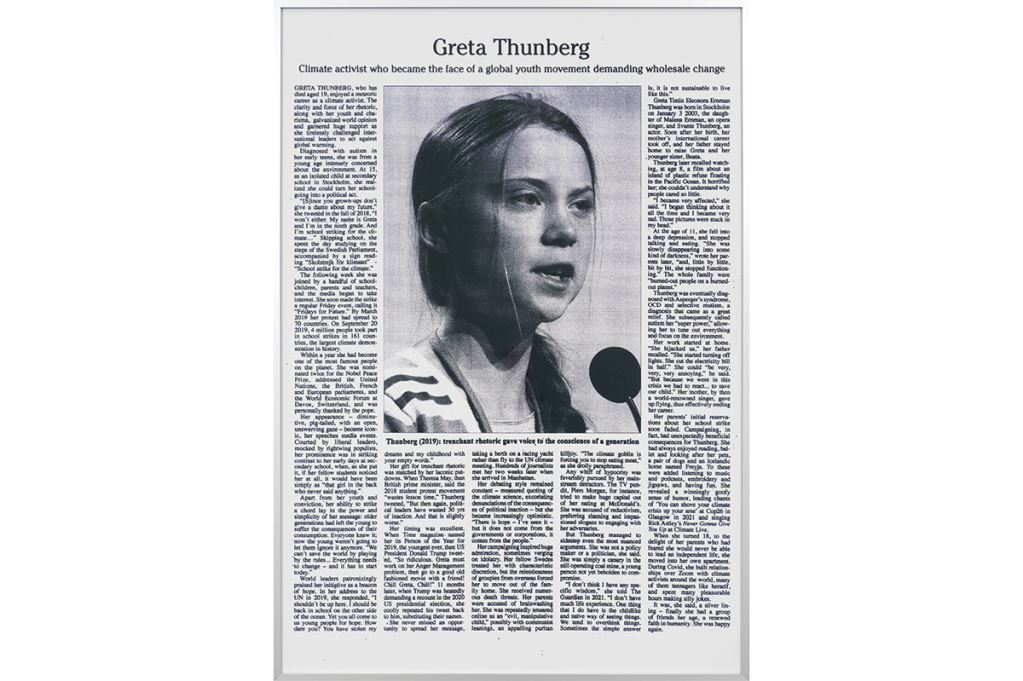

McEwen’s fictitious obituaries are small masterpieces of the uncanny. In the instant of reading one, the hypothesized death seems real. “It’s momentarily surprising because it hasn’t happened – although it will happen – but then it also has a built-in shelf life. You know that there will be an obituary that will look and read very much like this.” For a show at London’s Gagosian Gallery in 2023, McEwen unveiled a new set of obituaries – his first in a decade. Greta Thunberg, then at the height of her “child savior” fame, was one of the imagined deceased: “Her appearance – diminutive, pig-tailed, with an open, unswerving gaze – became iconic.” Grace Jones was another, “hailed as an Afro-futurist and pioneering queer icon.” Channeling the epitaphic style of Hugh Massingberd, Telegraph obituaries editor in the 1980s, McEwen slyly pried the “real person” from the public hagiography. But he insists that his role is minimal. “I’m really not doing anything. The obituaries make themselves. I feel that the less I do, the more space there is for the viewer.”

If McEwen’s work feels like a hybrid of British intellect and American conceptual cool, it’s no accident. His mother was American. His father, the artist and musician Rory McEwen – a renowned folk singer in the 1950s and 1960s – was friends with stars of the American art and music scenes. “If the Everly Brothers came to London, they’d call up my dad. He was a friend of Ed Ruscha’s – they traded works. I grew up with a Ruscha gunpowder drawing that says ‘Cheese-Chinese.’”

McEwen went to Oxford University, then the California Institute of the Arts. “I wanted the opposite of Oxford. I came from sandstone spires and CalArts wasn’t that. It was built to double as a hospital in case it failed as an art school – it had double-wide corridors so you could get two gurneys in there.”

McEwen’s fictitious obituaries are small masterpieces of the uncanny

CalArts, the leading art school in California, was a liberation. McEwen got to know Félix González-Torres and John Baldessari. The impact of Baldessari’s deadpan appropriations of photographs can be felt in many of McEwen’s works – for instance, a series of inkjet prints of stretch limousines in colored tints, made on the incongruous backing material of kitchen sponges. Among the first works he exhibited in New York were his obituaries of Malcolm McLaren (one subject who has since died) and Rod Stewart, followed soon after by parodies of shopwindow signs. One of these announced: “Fuck Off We’re Closed.” His work has since extended in multiple directions. An ongoing series of sculptures consists of meticulous three-dimensional replicas of everyday objects in machined graphite – an ATM or a drinking fountain, for instance, transfigured into a functionless carbon “double.” “Because of the material, it has a strange familiarity. One has seen that material in an HB pencil from the age of two. You don’t know if you’re remembering something or seeing something for the first time.”

“Fountain” (2009), which formed part of an exhibition in Hong Kong last year, carries inevitable echoes of Duchamp’s urinal. Another graphite sculpture, “Deepwater Horizon” (2020), recreates a minimalist sculpture by Carl Andre – a grid of square plates on the floor – with the addition, also in graphite, of two “rubber” ducks. “I was thinking: what if minimalism, instead of being a holy elixir that’s dripped down through the culture, were instead a kind of PFAS – a forever chemical? Something that seeps into the ground and never leaves.” In McEwen’s comical-dystopian reworking, the minimalist sculpture becomes a sort of oil spill, complete with oil-blackened birds.

In the painting “Laocoön” (2023), an air-conditioning unit is encased in a spiraling metal exoskeleton. In line with McEwen’s other paintings of mass-produced objects (air conditioners, Bic ballpoint pens, metal springs), he has employed a rote form of production – outsourcing the painting of the image to a company in China. The title invokes the coiling form of the Greco-Roman statue of the Trojan priest being strangled by a snake, but McEwen’s diagrammatic rendering (itself a nod to the graphic style of Roy Lichtenstein) is a thudding counterpoint to the original.

For German art historian Aby Warburg, the Laocoön was the exemplum doloris, or paradigm of agony. In McEwen’s archly clinical painting, the machine represents a duller horror: “That air conditioner came from when I was about six years old, and being in a hotel in New York. There was an air conditioner installed below the window, an ugly box spewing out cold air. I remember thinking, what is this hellish contraption?” The machine is symbolic, he says, of a human desire to control nature – which ultimately has to do with not wanting to die. Perhaps the gulf between McEwen’s “Laocoön” and the antique statue isn’t so great, after all.

It’s a strange time, McEwen reflects, to be an artist. He cites a news item from earlier this year, when Benjamin Netanyahu presented Donald Trump with a gold-plated pager – a macabre allusion to Israel’s use of explosive pagers to target Hezbollah. When life is as lurid as this, it’s hard for artists to compete. “I don’t understand the world right now,” he admits with a grim laugh.

But he has his own sense of direction. “I’ve been making these little paintings. They’re watercolor on canvas, and they’re very straightforward. I make them in my time, I don’t need help. It seems like a good time to be making things in that way.” McEwen recently moved from a warehouse-sized studio in Long Island City to a smaller space in Union Square. “I’m in the city, walking around, seeing the trash in the city and seeing people. I know I don’t understand the world from my phone – but maybe it’ll be easier to understand it from being in Union Square.”

Adam McEwen’s work is included in Route 19, curated by Adrian Dannatt, at the Belmacz gallery, London, until November 7. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 27, 2025 World edition.

Leave a Reply