“I am not a member of the make-it-ugly school,” Joan Mitchell told Irving Sandler for an ARTnews article in 1957. No argument there. As the major retrospective of more than eighty significant paintings by the second-generation Abstract Expressionist (1925-92), now on at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, reminds us, Mitchell’s artistic life was an unabashed pursuit of the beautiful. Her paintings, derived from nature but fired in the kiln of memory and intuition, are testaments to that pursuit, showing us at once just how devilishly out-of-reach true beauty can be, and just how important it is to stretch one’s arms and go for it.

Joan Mitchell, which will travel to the Baltimore Museum of Art after its run in San Francisco, is organized by Sarah Roberts of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and Katy Siegel of the Baltimore Museum of Art. It combines expansive panoramas, often comprising three or more canvases in polyptych arrangement, with small and intimate snapshot sonatas. Organized chronologically, the exhibition tracks Mitchell’s development from her student days to the last years of her life.

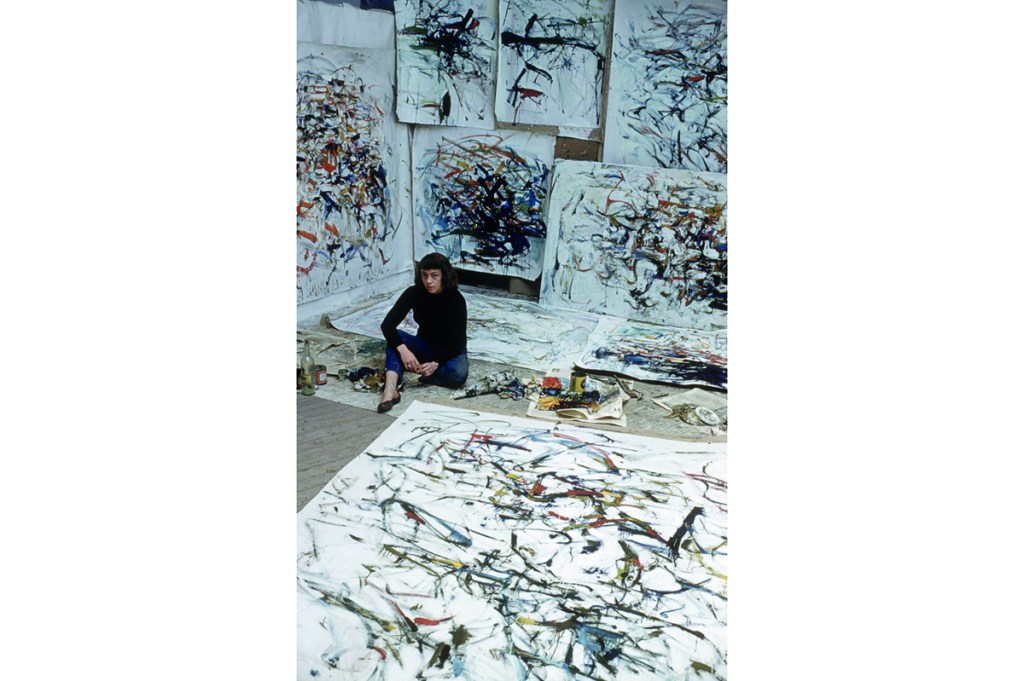

That chronology is useful insofar as it shows us just how her art changed over time; it’s easy to think of Mitchell as single-minded, someone whose entire career can be condensed into one kind of picture, despite her four decades as a mature painter. The words “Joan Mitchell” bring a clear hypothetical image to mind: There’s a large, wide canvas. Within a white field are athletic flicks and stabs of color — alluring, yes, but concrete in their physicality. No doubt about it, this is abstract painting. Yet step back and the entirety of the picture coalesces into something naggingly reminiscent of an experience of landscape, without ever rendering for a moment its literal transcription.

That’s a fascinating thing to do, and, in certain ways, the hypothetical does in fact sum up the vast majority of Mitchell’s work. Despite her avant-garde credentials, she was a self-proclaimed “conservative” painter, dedicated to a tradition of painting that placed beauty at its core. Born in 1925 to a wealthy Chicago family, Mitchell was raised in a home awash with culture. Her mother, Marion Strobel, the daughter of a steel magnate, had been an editor of Poetry magazine; literary luminaries such as Thornton Wilder and T.S. Eliot were regular guests at the Mitchell household. Her father, James, a prominent dermatologist who openly voiced his regret that Joan had been born a girl, encouraged her in sports — she took up diving, swimming, tennis and riding before settling on figure skating, in which she competed at the national level. James also compelled his precocious and creative daughter to choose at the age of eleven between painting or poetry, lest she end up only average at both.

“I chose painting,” recalled Mitchell. She threw her energies into art, at first delighting her ambitious parents, then perplexing them as she slowly but surely brushed her way out of the debutante’s path. Mitchell was sent to Smith College but transferred after an unexceptional year to the School of the Arts Institute of Chicago, committing for good to a life as a painter.

After graduating in 1948, she was off to New York City, where she commenced an earnest self-education in avant-garde painting. She visited the 57th Street galleries and identified Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline and Philip Guston as the best among New York’s ascendant Abstract Expressionists. But early efforts such as “Cross Section of a Bridge” (1951), on display in San Francisco, also betray the influence of older painters such as Arshile Gorky and even Marcel Duchamp. This helps to separate Mitchell from her innumerable peers, who merely parroted de Kooning’s latest whirlwind gestures or worshiped the ground that Pollock dripped on.

Things progressed steadily from those first stabs at all-over abstraction. By the mid-1950s Mitchell was already a force, garnering regular solo shows at the Stable Gallery, participating in important museum exhibitions such as the Whitney Annual and earning membership in “The Club,” the exclusive downtown debate-hall hangout where New York’s avant-garde elite battled over the aesthetic concerns of the day. Mitchell smoked, drank and quarreled with the best of them. The paintings improved as well. Earlier works like “Cross Section” were adept but depthless, assimilating the technical demeanor of Ab-Ex but without the resoluteness or urgency that this kind of painting requires. There was youthful potential in Mitchell, but yet unrealized. Many noted a decorative sensibility in the paintings, their innate tendency towards seductive colors amounting only to “Tasty French,” as they were sometimes disparagingly called.

In paintings such as “To the Harbormaster” (1957), however, the vigorous athleticism of Mitchell’s mark-making reaches a peak, calling attention to itself and wresting deeper meaning out of the tortured surface. Here, as with her other best work, we’re left with the strange feeling that, despite Mitchell’s maximalist intensity, perhaps even a single altered color might overripen the picture, making it sickly sweet — and that a different stray mark would collapse it all into a pile of mud.

“Mud” is an interesting word. We hear it thrown about in relation to Mitchell’s work of the late 1950s and 60s, in which the unmixed dazzlers are crowded out by neutral hues, yesterday’s lapidary sunshine by hurricane gloom. But as the painter and writer Fairfield Porter perceived in a 1961 review, Mitchell’s colors “are not muddy, which has nothing to do with the presence or absence of browns or grays, but with their being clearly what they are.” In other words, it’s not about saturation or lack of it, but about a color’s “just-rightness.” Is it the “correct” gray or brown, muted and assured like a stout Saxon verb, or does it wallow in vague hesitation? Mitchell once wrote that her chief aim in painting was “achieving accuracy and intensity,” two qualities that a lesser Expressionist might think inimical.

Mitchell continued to achieve successes, but the free-spirited individual began to feel the inhibiting squeeze of New York’s art world. Throughout the Fifties she had split her time between New York and Paris; after taking up with the Canadian painter Jean-Paul Riopelle in 1955, she moved to France permanently in 1959. While New York was pushing inexorably into the future — past Ab-Ex and into Pop, Minimalism, Conceptual Art, and beyond — Mitchell’s paintings looked in the opposite direction, becoming even more blatantly “French” in color and character: brighter, more “colorful” and gorgeous.The pulsating, mottled fields of gesture in “My Landscape II” (1967), in which subtle tones and hues emerge and recede, can’t help but remind us of Claude Monet’s late “Water Lilies,” a lineage that Mitchell alternately courted and rejected. Surely it was no coincidence that the estate she ultimately purchased in Vétheuil, outside Paris, included a house once owned by the Impressionist master.

As Cézanne once spoke of wanting to make something “solid and lasting” of Impressionism, perhaps even more important than Mitchell’s luminescent sense of color and light is her use of massing and weight to engage paint’s full expressive potential. In these later works, which kept getting better with the years, the diaphanous atmospheres of speckled color are played against lumpy, matter of fact, even ominous forms.

Mitchell kept painting into the early Nineties, even while battling the mouth cancer that ultimately killed her. Notoriously combative, she enjoyed calling herself une mauvais-herbe — a weed: unwanted, in your face and maddeningly resilient. It takes a Baudelairean eye to find beauty in these flowers of evil, and Mitchell had it. Witness “Weeds,” a 1976 diptych now owned by the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, DC. This conglomeration of mostly deep blue and blazing orange paint pushes all the oppositional forces of abstract painting — light and dark, warm and cool, fast and slow, thick and thin, angst and ease — into gripping tension.

“I want them to hold one image despite all the activity. It’s kind of a plumb line that dancers have; they have to be perfectly balanced, the more frenetic the activity is,” Mitchell said. At her best, she did it. This retrospective is a welcome chance to witness the achievement of her singular and tenacious vision.

Joan Mitchell is on view at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art until January 17, 2022. It can be seen at the Baltimore Museum of Art from March 6, 2022, until September 5, 2022. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2021 World edition.