In extraordinary scenes more reminiscent of a South American coup than a supposedly stable first world democracy, fights broke out between protestors supporting and opposing South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol, outside his presidential compound in an upscale suburb of Seoul. They were there to demand or resist Yoon’s arrest for his declaration of martial law last month.

Yoon, whose powers are currently suspended, is being defended by the PSS (Presidential Security Service) who are barring the way to government investigators now trying to figure out how to gain entry. Yoon’s personal security detail (200 strong) has fortified his compound and so far kept investigators at bay.

Unless the authorities seek a violent escalation, it may become a drawn-out legal battle

The PSS won the first round last Friday when after a six-hour stand-off, attempts to arrest the president were abandoned. The arrest warrant investigators were attempting to serve on that occasion expired on Monday, but a new one was issued almost immediately, hence their return.

It is not obvious how this situation will be resolved. Unless the authorities seek a violent escalation, it may become a drawn-out legal battle. Yoon’s lawyers have filed complaints arguing the warrants were filed in the wrong jurisdiction by prosecutors who were exceeding their authority. Meanwhile, Park Jong-joon the chief of Yoon’s security detail has denied allegations that his officers are acting as the president’s private army by stating that they are legally obliged to protect him.

But what of the South Korean people? Outside observers might be amazed that there are ordinary people willing to brave the freezing temperatures in Seoul to defend President Yoon, whose declaration of martial law, even if it only lasted a few hours, seemed outrageous. That hundreds have done so reveals how deeply polarized South Korean society is and how little trust in the authorities there is amongst certain groups.

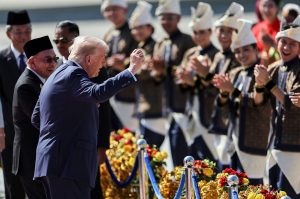

Broadly speaking those groups are fervently anti-communist, pro-America conservatives. Comparisons with January 6 in the US should not be belabored but there is a “Stop the Steal” atmosphere outside the compound now. Banners bearing those words along with US and Trump flags are being brandished by Yoon’s supporters, many wearing modified MAGA hats.

For these protestors, Yoon was the elected president and his mandate for change did appear to be being thwarted. Some believe the 2024 election, where his party was heavily defeated, was rigged and that Yoon is being targeted now as he was seeking to expose voting fraud. Yoon’s allegations of North Korean interference and anti-state forces are taken seriously by these groups.

There is a religion element to the pro-Yoon forces too. The conservative right in South Korea has long has drawn support from the evangelical Christian church and a committed Yoon supported the Rev. Jun Kwang-hoon spoke at a rally last week in defense of the martial law declaration. Many Koreans, especially those who fled the north, have adopted a strong Protestant Christian faith and retain an abiding fear and hatred of communism.

Though not an avowed Christian (he has latterly been accused of consulting a shaman), Yoon is believed to be at least sympathetic — he went to a missionary school and has a Christian name “Ambrose.” He attended an Easter service last year and posted a message on Facebook calling on South Koreans to “reflect on Jesus’ love for humanity.”

It would appear though that even some more moderate South Koreans have been induced to a measure of sympathy by the swiftness and severity of the action taken against Yoon. As evidence of this, and the widespread distrust of the opposition DPK (Democratic Party of Korea), an opinion poll conducted between January 3 and 4 by KOPRA saw Yoon’s ratings surpassing levels before the martial law declaration.

The vote for Yoon’s impeachment on December 14 and the issuance of the arrest warrants (for the first time in South Korean history) and the talk of dragging him out of his home, if necessary, may have spooked people, as has talks of treason charges and a possible life imprisonment, or even a death sentence.

Perhaps the suspension of Yoon’s powers, which effectively neutralize him until his fate is decided by the constitutional court in the Spring (he could be removed from office or reinstated) was sufficient punishment for now. The martial law declaration after all had a farcical element to it. It may have been a moment of madness by an under pressure leader possibly influenced by a desire to protect his supremely unhelpful scandal-wracked spouse.

If there is any positive outcome to all this mayhem it may be that since a country which rarely makes the news has rarely been out of it. If nothing else, this focus may enlighten people (such as the incoming Trump administration) as to the fragility of South Korean society, and the combustible nature of its politics. With its bellicose missile testing neighbor to the north showing no signs of being pacified, a better understanding of South Korea is of vital importance.